Ancient Roman Mass Grave Discovered in Vienna: A Glimpse into the Past

In a remarkable archaeological find, construction workers renovating a sports field in Vienna uncovered a mass grave that dates back to the mid-first century to early second century CE. This significant discovery, made in October of last year, has provided fresh insights into the tumultuous interactions between Roman legionaries and Germanic tribes near the Danube River, a site of historical conflict.

Experts from the Vienna City Archaeology Department, along with the archaeological service provider Novetus GmbH, have analyzed the skeletal remains and determined that they likely belonged to soldiers who perished during a battle involving ancient Roman forces. The details surrounding this discovery were elaborated upon in a press release issued by Wien Museum on Wednesday.

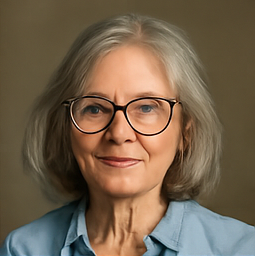

Veronica Kaup-Hasler, the Executive City Councillor for Culture and Science in Vienna, expressed her excitement over the find. “In Vienna, one is always prepared to encounter Roman traces as soon as one opens up a pavement or opens the earth: after all, Vindobona laid the foundation stone of our city,” she stated. Vindobona, the ancient Roman military camp and settlement that eventually evolved into modern-day Vienna, is integral to the city’s historical identity. Kaup-Hasler referred to the mass grave discovered in Simmering, a district of Vienna, as a “true sensation” that offers a unique perspective on the origins of the city.

The mass grave itself contained the remains of approximately 150 individuals, all of whom were found to be male, predominantly aged between 20 and 30 years. Initial examinations revealed that these individuals exhibited minimal signs of infectious diseases, suggesting they were likely healthy at the time of their deaths. However, the skeletal remains displayed clear evidence of traumatic injuries consistent with combat, including wounds from daggers, spears, swords, and other weaponry, which were the likely causes of death.

Michaela Binder, a senior anthropologist involved in the analysis at Novetus GmbH, noted the significance of these findings. “Based on the arrangement of the skeletons and the fact that they are all male remains, it can be ruled out that the site was connected to a hospital or similar facility, or that an epidemic was the cause of death,” she confirmed. The evidence points decisively to violent conflict as the reason for their demise.

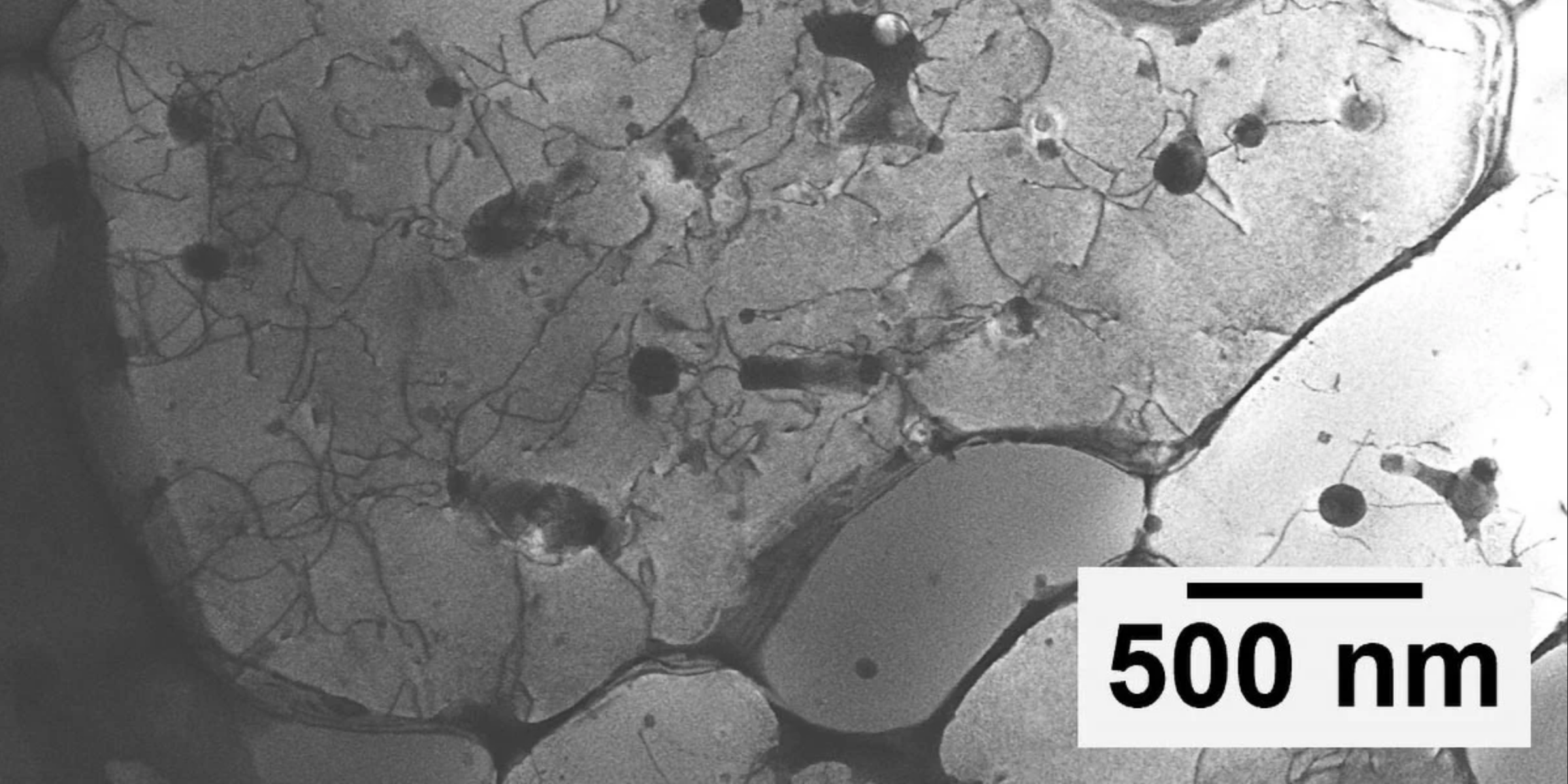

In addition to the human remains, the excavation yielded various artifacts, including armor scales, lance tips, a helmet cheek piece, shoe nails, and a fragmented iron dagger. Notably, the dagger proved instrumental in dating the burial site; X-ray images of the sheath revealed distinctive decorations characteristic of ancient Roman craftsmanship, specifically silver wire inlays that place its creation between the mid-first century and early second century CE. Christoph Öllerer, the deputy head of the Vienna City Archaeology Department, emphasized the rarity of such discoveries: “Since cremations were common in the European parts of the Roman Empire around 100 AD, inhumations are an absolute exception. Finds of Roman skeletons from this period are therefore extremely rare.”

This discovery holds substantial local significance as it represents the first direct archaeological evidence of a battle along the Danube Limes, which formed part of the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Historical records indicate that during the rule of Emperor Domitian from 81-96 CE, there were ongoing battles between Roman forces and Germanic tribes along the empire’s borders, which likely influenced Emperor Trajan's subsequent decision to expand the Danube Limes. Until now, knowledge of these conflicts was primarily based on historical texts rather than physical evidence.

Archaeologist Martin Mosser from the City Archaeology Department elaborated on the implications of the finding, suggesting that the ancient battle could have been a significant factor in the transformation of the small military base into the larger legionary camp known as Vindobona, located less than seven kilometers from the site of the grave. This archaeological discovery may thus illuminate the early chapters of Vienna’s urban development and history.