Threatened Gangetic Dolphins: India's National Aquatic Animal Faces Survival Challenges

India's longest and most revered river, the Ganges, is not only significant for its cultural and religious importance but also serves as a crucial habitat for thousands of dolphins. However, the survival of these remarkable creatures is increasingly under threat.

Unlike their oceanic relatives, these dolphins do not leap gracefully out of the water or swim upright; instead, they have adapted to the unique conditions of river life. Known as Gangetic dolphins, these river dolphins have elongated snouts, swim sideways, and are almost entirely blind, relying on echolocation to navigate through the murky waters. As India's national aquatic animal, they occupy a prominent place in the country's biodiversity.

A comprehensive survey recently conducted has revealed that India is home to approximately 6,327 river dolphins, with 6,324 being Gangetic dolphins and a mere three Indus dolphins. The Indus dolphins primarily reside in Pakistan, as the river flows through both South Asian nations. Both species are classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), underscoring the urgent need for conservation efforts.

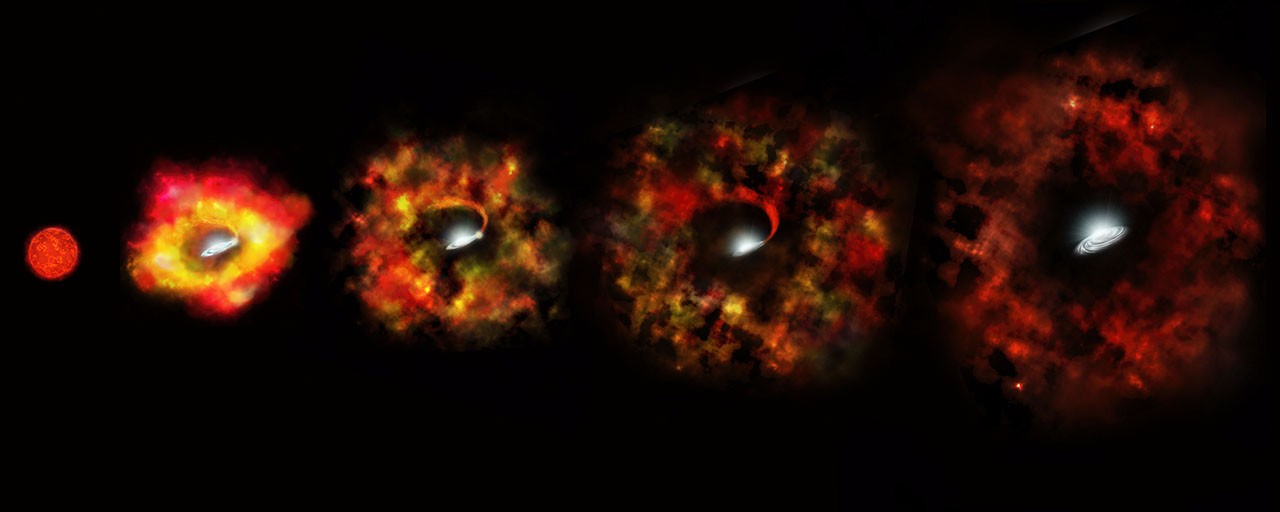

The survey, carried out by researchers from the Wildlife Institute of India, spanned 58 rivers across ten states between 2021 and 2023, marking the first comprehensive count of India's river dolphins. This effort is particularly significant, as river dolphins have a unique evolutionary history. Often referred to as 'living fossils', these creatures evolved from marine ancestors millions of years ago. During prehistoric times, as the seas flooded low-lying areas of South Asia, these dolphins ventured inland, adapting to life in rivers once the waters receded.

Despite their resilience, the challenges facing river dolphins are manifold. Since 1980, over 500 dolphins have perished due to various human activities, including accidental entanglement in fishing nets and deliberate killings. Conservationist Ravindra Kumar Sinha points out that until the early 2000s, awareness about the plight of river dolphins was alarmingly low. In a bid to boost conservation efforts, the Gangetic river dolphin was declared India's national aquatic animal in 2009. Initiatives like a 2020 action plan and the establishment of a dedicated research centre in 2024 have been launched to help improve their population numbers.

Nevertheless, experts caution that much work remains to be done. Dolphins continue to be hunted for their flesh and blubber, which serve as bait for fishing. Additionally, they often collide with boats or become ensnared in fishing lines, leading to a tragic fate. According to Nachiket Kelkar from the Wildlife Conservation Trust, many fishermen refrain from reporting accidental dolphin deaths, fearing legal repercussions. Under Indian wildlife laws, both accidental and intentional dolphin killings are treated as 'hunting' and carry severe penalties. Consequently, numerous impoverished fishermen discreetly dispose of the carcasses to evade fines.

Moreover, the rise of river cruise tourism in India over the past decade poses an additional threat to dolphin habitats. A growing number of cruise trips operate along the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, which raises concerns among conservationists. “There is no doubt that disturbances from cruises will severely impact the dolphins, which are sensitive to noise,” warns Sinha. He draws a parallel between the Gangetic dolphins and the now-extinct Baiji dolphins from China's Yangtze River, emphasizing that increased vessel traffic could drive Gangetic dolphins to a similar fate.

River dolphins’ adaptations to their environment also contribute to their vulnerability. Almost blind, they rely heavily on echolocation—high-pitched sound pulses that bounce off surrounding objects—to navigate through their murky environments. While this survival trait serves them well in their natural habitat, it also exposes them to modern threats. Their poor eyesight and relatively slow swimming speeds increase their likelihood of colliding with boats and other hazards. Additionally, their slow reproductive cycle compounds their vulnerability, as females typically give birth to just one calf every two to three years, maturing between six and ten years of age.

Despite these daunting challenges, Sinha remains optimistic about the future of river dolphins in India. “Government initiatives have played a significant role in safeguarding the dolphins. While a lot has been accomplished, a great deal more work lies ahead,” he asserts, emphasizing the ongoing need for public awareness and conservation efforts to ensure the survival of these unique aquatic mammals.