Discovery of Lokiceratops rangiformis: A New Horned Dinosaur Challenges Our Understanding of Evolution

A groundbreaking discovery in the field of paleontology has unveiled a newly described species of horned dinosaur named Lokiceratops rangiformis. This remarkable dinosaur is stirring excitement within the scientific community due to its impressive size, uniquely ornate frill, and significant implications for our understanding of ceratopsian evolution. The details of this fascinating dinosaur were published in a recent study in PeerJ. Notably, Lokiceratops not only represents the largest and most ornately adorned member of its family discovered to date, but it also challenges long-held assumptions about ceratopsian diversity and behavior.

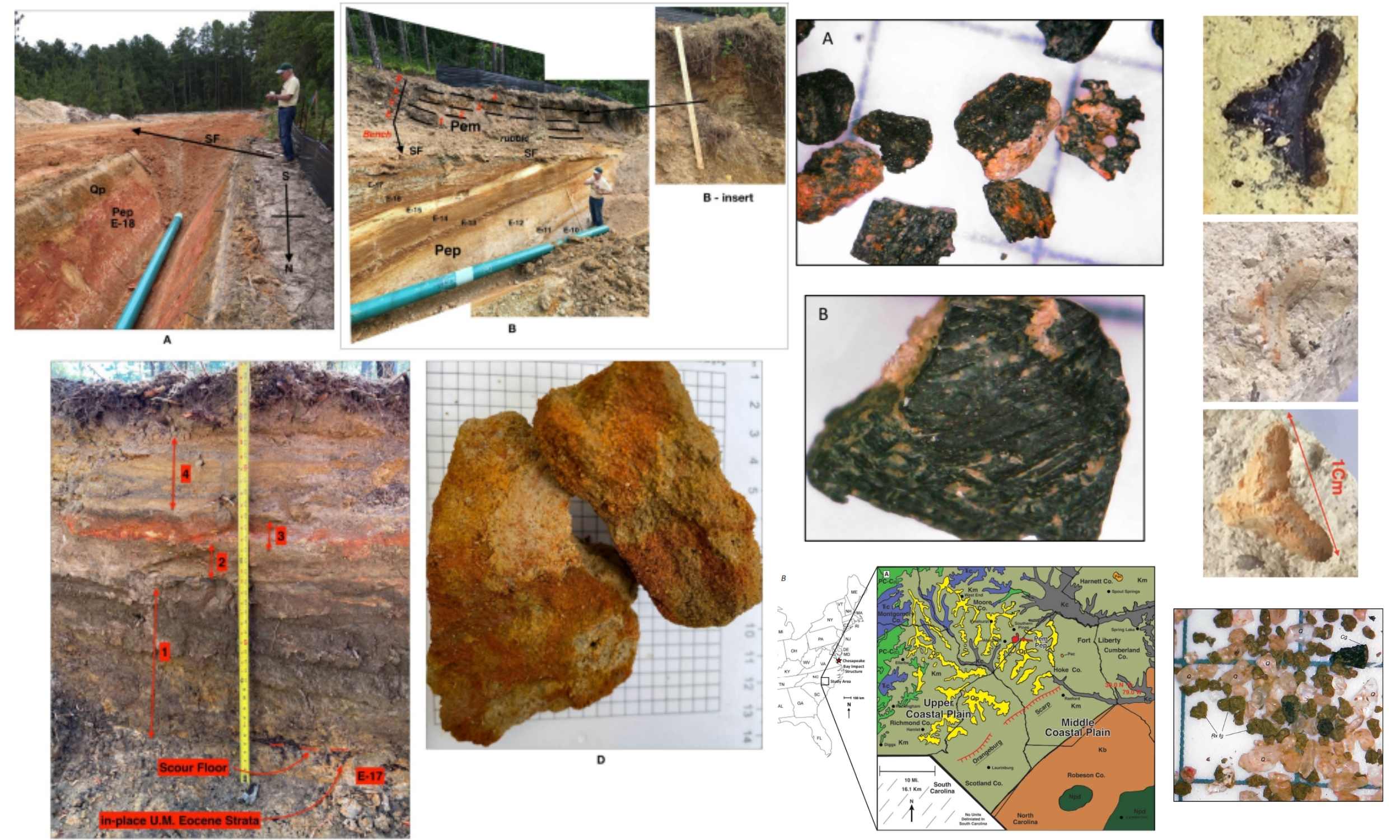

The discovery site of this dinosaur is particularly intriguing. Fossil hunters unearthed a partial skull of Lokiceratops in northern Montana, just below the border between the United States and Canada. Although the skull is incomplete, it contained enough significant details to astonish paleontologists Mark Loewen and Joseph Sertich, who were involved in the study. The dinosaur's skull, reconstructed from large bone fragments, showcased dramatic, blade-like horns and a sweeping frill ornamentation that is unlike any other centrosaurine dinosaur previously identified.

In a nod to Norse mythology, the name Lokiceratops was chosen due to the striking resemblance of its curving horns to the mythological trickster god Loki. As Loewen explained, “The dinosaur now has a permanent home in Denmark, so we went with a Norse god. In the end, doesn’t it just really look like Loki with the curving blades?” The species name rangiformis means “caribou-like,” which reflects the animal’s antler-like display features. This dinosaur was an impressive 22 feet long and weighed around 11,000 pounds, establishing itself as a heavyweight among its relatives that roamed the wetlands of the Western Interior Seaway approximately 78 million years ago.

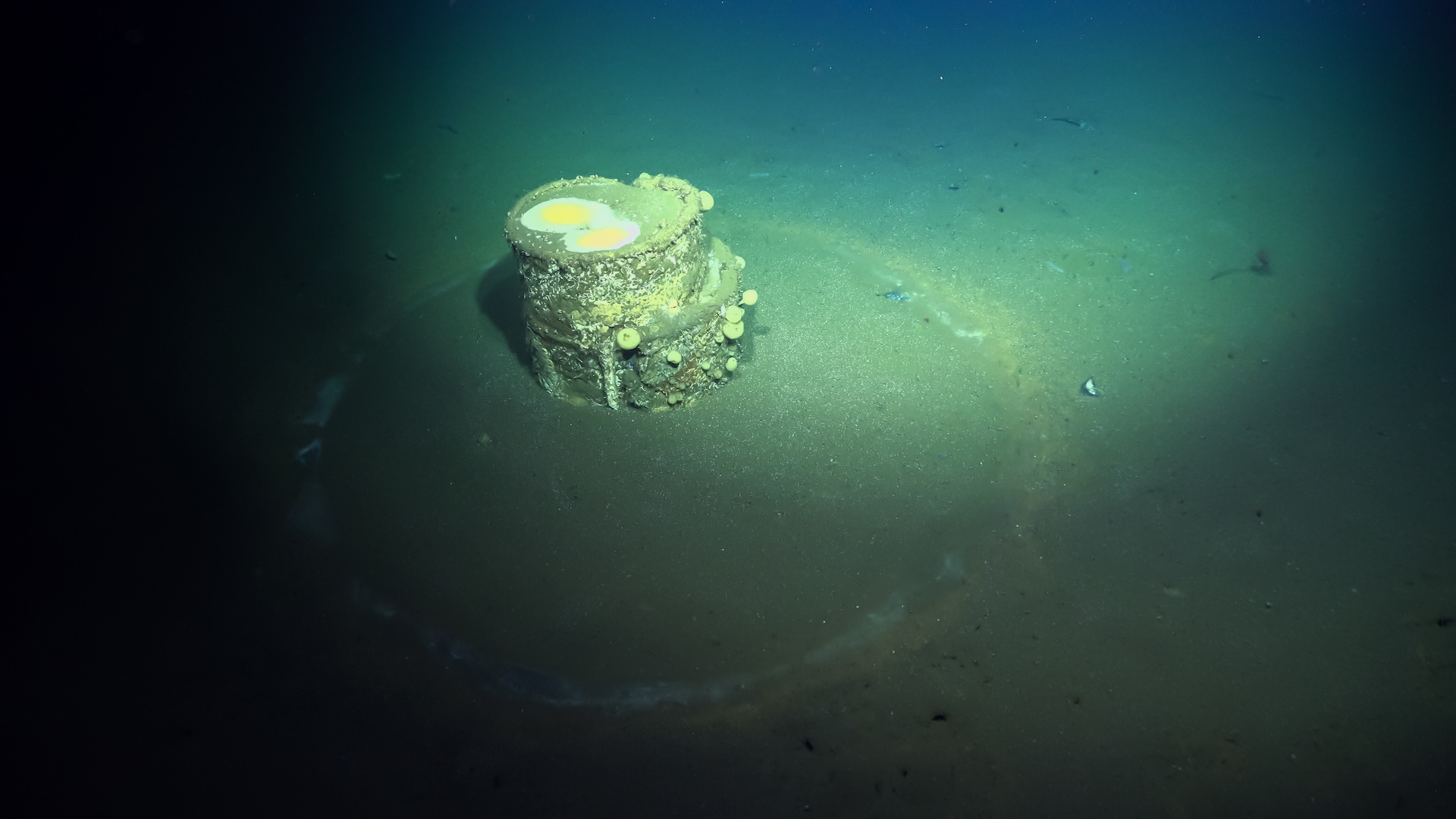

The mounted skull of Lokiceratops rangiformis is currently exhibited at the Museum of Evolution in Maribo, Denmark, where it continues to fascinate visitors and researchers alike.

Beyond its striking physical stature, the most significant findings surrounding Lokiceratops relate to its skull ornamentation, which provides critical insights into the behaviors and evolutionary pathways of dinosaurs. Unlike many of its close relatives, Lokiceratops features two asymmetrical brow horns and notably lacks a nose horn. Researchers believe these features were not primarily used for combat but had important visual and social functions in the animal's life.

“These skull ornaments are among the keys to unlocking horned dinosaur diversity and demonstrate that evolutionary selection for showy displays contributed to the dizzying richness of Cretaceous ecosystems,” Sertich articulated during the unveiling of the fossil. The researchers propose that such extravagant traits evolved in a similar manner to peacock feathers or bird crests, driven by both sexual selection and the need for species recognition.

“We think that the horns on these dinosaurs were analogous to what birds are doing with displays,” Sertich elaborated. “They’re using them either for mate selection or species recognition.” In ecosystems where several nearly identical species existed, these visual signals would have played an essential role in maintaining reproductive boundaries among different populations, preventing interbreeding.

The revelation that Lokiceratops was one of five distinct ceratopsian species cohabiting the same narrow region during the Late Cretaceous period has sent shockwaves through the paleontological community. All five species were discovered within the same geological layer known as the Kennedy Coulee Assemblage, a fossil-rich area that spans northern Montana and southern Alberta.

“Finding five living together represents unheard-of diversity, similar to what you would see on the plains of East Africa today with different horned ungulates,” Sertich remarked. The coexistence of these species within such close proximity contradicts previous assumptions that large herbivores tended to be more dispersed. Instead, this finding suggests a highly localized prehistoric population, leading to the evolution of distinctive features within relatively small, semi-isolated habitats.

The diverse horn shapes among these species were not merely decorative; they served critical evolutionary purposes for coexistence in tightly packed ecosystems. The differential ornamentation helped to reduce direct competition and prevent interbreeding, echoing the mechanisms seen in modern antelope species that differentiate themselves in the African savannahs.

This discovery also highlights the vital role of geographic isolation and environmental fragmentation in promoting evolutionary diversity among horned dinosaurs. Unlike today’s herbivorous species that tend to roam over vast distances, ceratopsians such as Lokiceratops seem to have remained within localized habitats. Minor shifts in their environments—whether concerning vegetation, climate, or soil—may have prompted significant anatomical changes over relatively short evolutionary timescales.

“Lokiceratops helps us understand that we are only scratching the surface when it comes to the diversity and relationships within the family tree of horned dinosaurs,” Loewen commented. This insight repositions Laramidia, the ancient landmass where these dinosaurs thrived, as a dynamic environment that significantly influenced ceratopsian evolution. Isolated ecosystems acted as incubators for species differentiation, resulting in a stunning variety of horn displays akin to modern bird plumage.

The implications of this research extend far beyond this newly discovered species. The study updates the centrosaurine family tree and suggests that many more species could be awaiting discovery in the rich fossil beds yet to be excavated. Much like Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos Islands, each isolated group appears to have evolved its own distinct identity rooted in visual display, enriching our understanding of the complex web of life that existed during the Cretaceous period.