Children of Radium — Joe Dunthorne’s family memoir balances trust and doubt

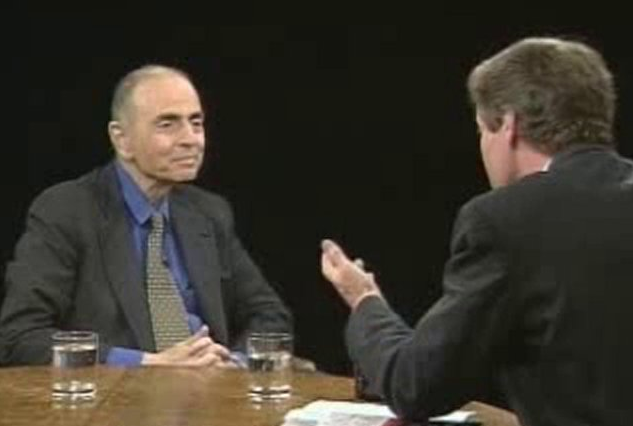

Every family has stories that are passed down the generations, worn so smooth by retelling that the facts behind them become smudged. For the family of Joe Dunthorne — the author of three very funny novels and a smart collection of poetry — the stories are all about his great-grandfather, German scientist Siegfried Merzbacher. So this family memoir opens irresistibly — “My grandmother grew up brushing her teeth with radioactive toothpaste” — with one of Siegfried’s crackpot inventions. It continues in sparky style as we learn that Siegfried and his children fled to Turkey in 1935 as Jewish refugees along with other exiled intellectuals (“essentially the Bloomsbury group but with better weather”), only to return to Germany the following year under cover of the Summer Olympics. But all of this information comes from Dunthorne’s grandmother, who is not necessarily a reliable source. And besides, when she died in 2017, “while they all agreed that she had said unforgettable things, no one could remember what they were”. Dunthorne wishes to navigate his own feelings of trust and doubt — two sides of one coin — and get to the bottom of Siegfried’s history. Happily, his great-grandfather wrote his own life story, a mammoth 2,000-page typescript that nobody else in the family has managed to get all the way through. Children of Radium then is a triangulation between what Dunthorne finds in Siegfried’s memoir and what he learns from his own research. That radioactive toothpaste turns out to be a MacGuffin, mentioned briefly but really a teasing way into a much darker story. In the 1920s, we learn, Siegfried was involved in the development of gas chemical weapons — in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles — which may later have been used not only by the Nazis but in the Turkish Dersim massacre of the late 1930s. It is hard for Dunthorne to be sure about any of this. He’s thwarted by Siegfried’s memoir, which repeatedly skirts the lip of the slippery pit of his involvement, before darting away. Siegfried will touch on, for example, the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s before quickly changing track: “From this unpleasant subject I now return to my childhood vacations.” So this book becomes Dunthorne’s self-aware performance of an investigation: reading the memoir, writing about reading it, suggesting his own conclusions, and getting out of the house himself to fill in the gaps. He heads — with a Geiger counter purchased on eBay — to Oranienburg, the German town just north of Berlin that housed two concentration camps and a chemical plant. Is this, he wonders, “a place where fumes still lingered from a poison made according to my great-grandfather’s instructions”? Did Siegfried have an “unshiftable burden on his conscience” that may explain both his need to write his life story, and his need to evade the more difficult parts? Children of Radium is a relatively short book, not because it lacks substance but because Dunthorne carefully fillets his vast material for the most vivid details. We learn that gas vans, “the Nazis’ first mass-killing technology”, were discontinued because “the sound of [victims’] screaming and throwing themselves against locked doors was found to be upsetting” — for the drivers. And that Nazi doctor Ernst-Robert Grawitz killed himself and his family in 1945 when, as “he sat with his wife and son, he held two grenades in his hands underneath the dining table”. Dunthorne’s spry style doesn’t dilute the force of his story. What does dilute it is the widening out of his investigation, in the final third of the book, to family members and connections whose stories are less urgent than Siegfried’s. Still, this is a valuable account which seeks neither to praise Siegfried nor to bury him. And if his family’s escape from Nazi Germany was “predicated on complicity”, Dunthorne writes, isn’t it vital that “we should feel able to recognise such ambiguities, because how else will we ever see each other as fully human?”. Ah, but seeing each other as fully human has never been guaranteed. In the years after the war, polls carried out in the newly created West Germany found that a majority thought Nazism was a “good idea badly carried out”. And as the far right makes electoral gains all across Europe, what Dunthorne calls “a buried inheritance” doesn’t seem so very far beneath the surface. Children of Radium: A Buried Inheritance by Joe Dunthorne Hamish Hamilton £16.99/Scribner $28.99, 320 pages Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X