Nematodes Forming Towers in Nature: A New Discovery

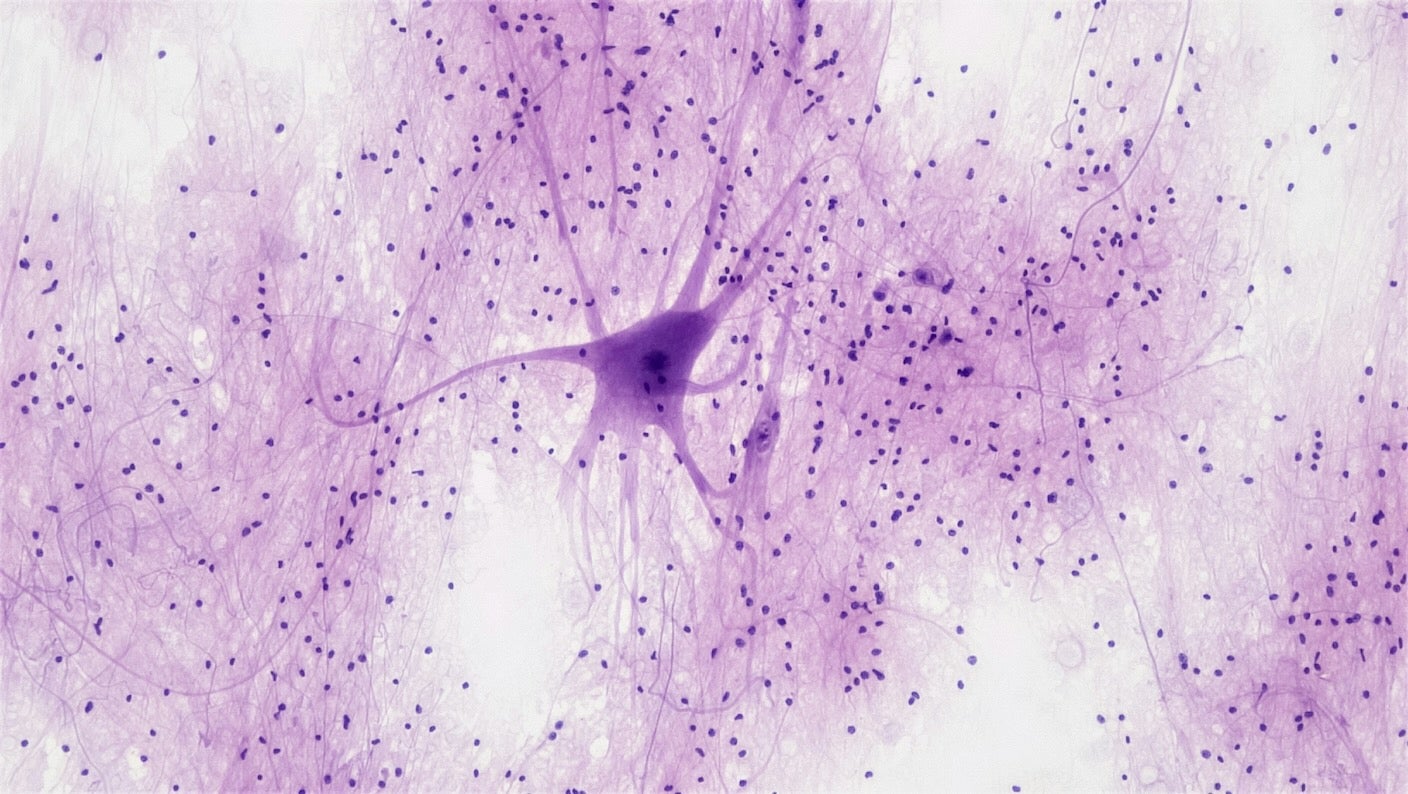

In a groundbreaking report published in the esteemed journal Current Biology, researchers have observed nematodes exhibiting a remarkable behavior: forming writhing towers of tiny worms in their natural habitats for the very first time. This astonishing discovery, which challenges previously held beliefs about the behavior of these microscopic creatures, was made by a dedicated team from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior (MPI-AB) and the University of Konstanz in Germany.

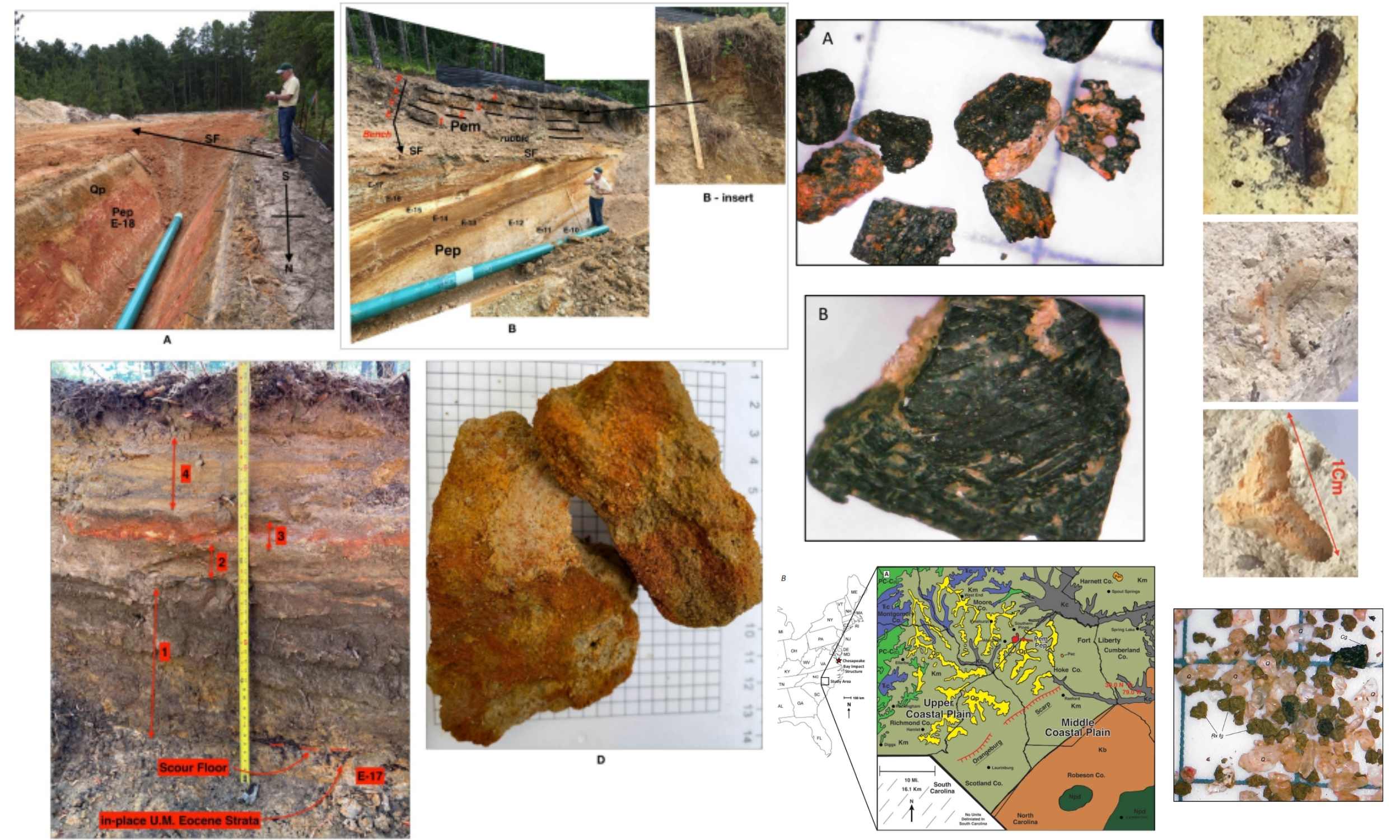

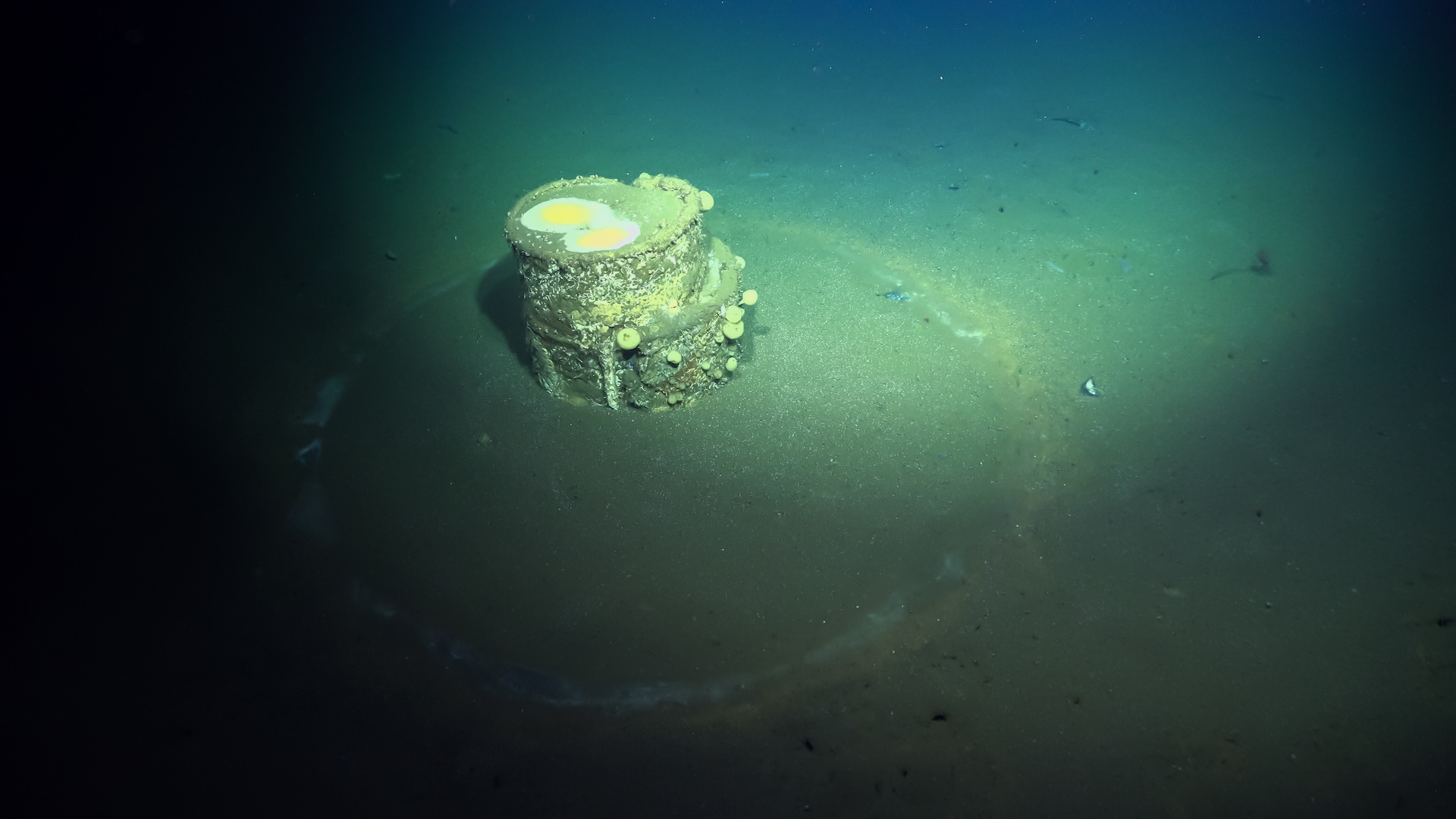

Previously, the peculiar phenomenon of nematodes constructing towers had only been documented in controlled experimental conditions, where it was assumed that this behavior served as a competitive strategy for escaping the rest of the group. However, the stunning new footage captured in local orchards shows that these towers may serve a more cooperative and mutually beneficial purpose, providing insights into the social dynamics of nematodes.

The researchers were fortunate to document the towers as they formed on fallen apples and pears in the orchards around Konstanz. This serendipitous observation was coupled with follow-up laboratory experiments, leading the team to conclude that the “towering” behavior is indeed a natural occurrence, demonstrating a fascinating mode of mass transit among the worms.

“I was ecstatic when I saw these natural towers for the first time,” shared Serena Ding, the senior author of the study and a group leader at MPI-AB. She vividly recounted her excitement when co-author Ryan Greenway, a biologist from the University of Konstanz, sent her a video of the phenomenon from the field. “For so long, natural worm towers existed only in our imaginations. But with the right equipment and lots of curiosity, we found them hiding in plain sight.”

This curiosity also led to intriguing revelations surrounding the cooperative behavior of the worms. The team noted that while several species of nematodes crawled over the fruit, only a specific species in a key developmental stage—the durable larval form known as “dauer” (which translates to “eternal” in German)—participated in the construction of these towers. This level of specificity suggests that the behavior may be driven by more than just random congregation.

A nematode tower, as explained by the study's first author, Daniela Perez, a postdoctoral researcher at MPI-AB, represents much more than an uncoordinated pile of worms. “It’s a coordinated structure, a superorganism in motion,” she emphasized, highlighting the complexity of this behavior.

The implications of this research are significant, as the paper posits that these observations could serve as a crucial “missing link” in understanding the behavior of similar organisms. Towering behavior is not entirely unprecedented in nature; it has previously been documented in slime molds, fire ants, and spider mites. However, the occurrence of such behavior in nematodes remains relatively rare and opens doors for further inquiry.

To explore whether other types of worms could produce similar “superorganism” structures, researchers turned their attention to the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, a model organism widely used in biological studies. They devised an innovative experiment using a toothbrush bristle as a scaffold in a food-free agar plate. When the worms were released, within a mere two hours, they began to form a tower around the bristle, some extending exploratory “arms,” while others bridged gaps between spaces. Remarkably, when researchers tapped the top of the burgeoning structure with a glass pick, the worms responded by wriggling toward the stimulus.

“The towers are actively sensing and growing,” noted Perez. “When we touched them, they responded immediately, growing toward the stimulus and attaching to it.” This led the researchers to wonder about the presence of any hierarchical structure within the worms: Did younger or stronger worms take on more responsibility?

Surprisingly, the roundworms displayed a highly egalitarian approach to tower building. Unlike the orchard-based nematodes, the laboratory-bound C. elegans represented a diverse range of developmental stages, from larval to adult, yet all members contributed equally to the tower’s construction. This finding suggests that “towering” may not just be a species-specific behavior but could represent a more generalized strategy for collective movement.

“Our study opens up a whole new system for exploring how and why animals move together,” concluded Ding, paving the way for future research into the social behaviors of nematodes and potentially other organisms as well.