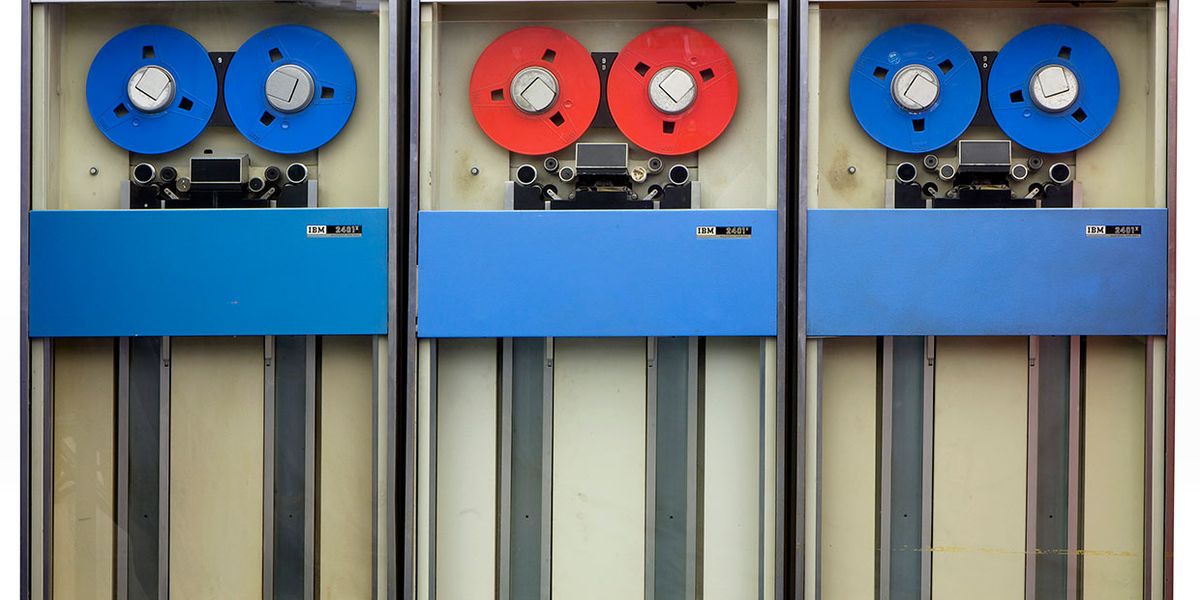

The Impact of IBM's System/360: A Revolutionary Milestone in Computing

The IBM System/360, launched on April 7, 1964, is often heralded as one of the most transformative products of the last century and a half, alongside groundbreaking inventions like the lightbulb and Ford's Model T. This series of mainframe computers not only altered the landscape of the computer industry but also revolutionized operations within businesses and government bodies, significantly enhancing productivity and enabling a multitude of new tasks.

However, the journey leading up to this monumental launch wasnât without its challenges. In the years preceding its debut, the development of the System/360 was marked by intense internal conflict within IBM. The project showcased the companyâs commitment at every level, but the process was fraught with what science policy expert Keith Pavitt termed âtribal warfare.â Competing factions within the company faced off in a chaotic environment that was rife with uncertainty and technological ambiguity, complicating the task of creating and deploying this groundbreaking machine.

Despite these hurdles, IBM's considerable resources in terms of talent, funding, and materials ultimately facilitated the successful launch of the S/360. The companyâs ability to harness emerging technologies from various segments of its enterprise, albeit in a seemingly disorganized manner, highlighted a unique form of entrepreneurial spirit. This apparent chaos belied the success that would follow, offering invaluable lessons in the domain of innovation.

By the close of the 1950s, computer users were facing a daunting challengeâthe existing systems were inadequate to support the burgeoning demands of businesses aiming to automate their operations. The introduction of the IBM 1401 mainframe marked a pivotal moment, as over 12,000 of these systems were sold between its launch in 1959 and its retirement in 1971. However, the limitations of the 1401 became apparent as users began to outgrow its capabilities, leading to a pressing need for a more scalable solution.

Organizations quickly discovered that the 1401, while popular, was not expandable or upgradeable. Faced with this dilemma, customers had a difficult choice: transition to a larger IBM model like the IBM 7000, switch to a competitorâs system, or invest in additional 1401 units. Each option presented significant challenges, including the high costs associated with rewriting software for different systems and the need for retraining staff. As they clamored for a system that was both upgradable and compatible, customers expressed a desire for a solution that the industry could not yet provide.

Compounding the issue, IBM's internal divisions were creating friction. Engineers at IBMâs Endicott facility, the birthplace of the 1401, resisted the idea of developing larger systems, leading to a rivalry with their counterparts at Poughkeepsie. This rivalry manifested itself intensely, with one engineer recalling that the internal competition was sometimes more intense than that with external rivals. This internal conflict resulted in growing customer pressure on IBM to create a seamless upgrade path from the 1401 to larger systems, emphasizing the need for compatibility.

Recognizing this imperative, IBM's senior management concluded that a single, unified system would simplify production and reduce research and development costs, allowing the company to remain competitive amidst increasing rivalry. The launch of the IBM 1410 in 1960 demonstrated the power of compatibility, as it retained compatibility with the 1401, much to the approval of both customers and sales teams.

Faced with these challenges, T. Vincent Learson, then vice president of manufacturing and development, implemented strategies to dismantle the rivalry within IBM. Learson introduced a management approach known as âabrasive interaction,â which involved reshuffling personnel to encourage collaboration between competing factions. He replaced the Poughkeepsie manager overseeing the 8000 series with Bob O. Evans, who had successfully managed the development of the 1401 and 1410.

Evans was a strong advocate for compatibility among IBMâs future products. After assessing the landscape, he recommended halting work on the 8000 project to focus on developing a cohesive product line. His proposal for a new technology called Solid Logic Technology (SLT) was intended to enhance the competitiveness of IBM's machines.

Despite initial resistance from prominent engineers like Frederick P. Brooks Jr., who had led the design of the 8000, collaboration soon became the order of the day. Learson assembled a task force to concentrate on producing a compatible family of computers, leading to the advent of the System/360. Their strategy entailed developing five compatible processors, enabling users to upgrade without the need for extensive software rewrites.

In the midst of these developments, a serendipitous breakthrough occurred in mid-1963 when engineers discovered that microcode could be added to the new computers to allow them to simulate the earlier IBM models. This innovation meant that 1401 software could run on the new machines, albeit at faster speeds, boosting sales enthusiasm and urgency.

As the company prepared for the S/360 launch, IBM executives understood the enormity of their undertaking. Coordinating the hardware and software across multiple teams was daunting, as was the challenge of manufacturing the necessary electronic components. IBM opted to produce its own integrated circuits, an expensive venture that underscored the risks involved.

On April 7, 1964, IBM Chairman Thomas J. Watson Jr. officially unveiled the System/360 to an audience of over 100,000 customers, reporters, and industry experts gathered across 165 cities globally. The announcement marked the introduction of a staggering 150 new products, including six computers and 44 peripherals, and promised the software necessary for cohesive functionality.

The core feature of the System/360 was its unparalleled compatibility, allowing organizations to scale their computing capabilities seamlessly. Customers could start with a smaller model and upgrade without the hassle of rewriting software or replacing peripheral equipment. The term '360' was deliberately chosen to convey a sense of completeness and versatility.

In the month following the launch, over 100,000 systems were ordered worldwideâan astonishing figure considering that the entire UK, Western Europe, the US, and Japan had just over 20,000 computers combined at the time. IBM had essentially secured itself a two-year head start with the lead time between the announcement and the first deliveries scheduled for the third quarter of 1965.

However, this period also marked one of the most turbulent phases in IBM's history. The company invested an unprecedented $5 billion (about $40 billion in todayâs dollars) into the development of the System/360, which was more than its total revenue in a single year. This financial commitment reflected the belief that failure would spell doom for IBM.

Despite the ambitions, production issues quickly emerged. Manufacturing was tasked with doubling output in 1965, leading to quality control failures in the newly developed SLT modules. As production difficulties escalated, the quality assurance department flagged 25% of all modules, resulting in significant delays.

Nevertheless, by 1966, manufacturing had ramped up significantly, producing 90 million SLT modules and opening new plants to meet demand. IBM also struggled with production consistency in memory components, prompting them to seek craftsmanship expertise internationally, including from skilled workers in Japan.

As the manufacturing process evolved into a global effort, further complications arose in coordinating different facilities and activities. In response to the ongoing issues, Watson took decisive action, removing Arthur Watson from his managerial role and replacing him with Learson, who then brought on a team of four engineering managersâdubbed the âfour horsemenââtasked with resolving the myriad challenges.

While software production faced its own set of challenges, with early versions struggling to run multiple jobs concurrently, the project saw an influx of resources as IBM hired additional programmers to expedite development. Despite the tumult, by 1965, hundreds of medium-sized S/360 units were shipped to customers, albeit not always meeting the original specifications due to quality issues.

Competitors quickly responded to IBM's S/360 announcement by developing their own systems, some compatible with IBMâs offerings while others were designed to operate independently. Yet, the S/360 fundamentally transformed the computing landscape, leading to a dramatic increase in installed computers globally and contributing to the overall growth of the industry. By the end of the 1960s, IBMâs share of the market had expanded significantly, reinforcing its status as a dominant player in the computer industry.

In conclusion, the launch of the IBM System/360 was not merely the introduction of a new product; it was a seismic shift that shaped the future of computing. Though the process was fraught with obstacles, the ultimate success of the S/360 would come to define IBM and the industry for decades to follow.