Trump's Tariffs Spark Global Economic Turmoil

WASHINGTON In a bold move that has sent shockwaves through global financial markets, President Donald Trump has initiated what many are calling a trade war against various nations worldwide. This drastic action has not only elevated the risk of a potential recession but has also jeopardized the long-standing political and economic alliances that have historically underpinned global commerce since the end of World War II.

The latest wave of tariffs imposed by the Trump administration officially took effect at midnight on Wednesday, resulting in significantly higher import tax rates on goods from a multitude of countries and territories. Economists are left bewildered by Trump's insistence on reshaping the global economic landscape, particularly given that he inherited one of the strongest economies in recent history.

Eswar Prasad, a professor of trade policy at Cornell University, noted the irony in Trump's claims of unfair treatment towards the American economy at a time when it was experiencing robust growth, while many other major economies were struggling. There is a deep irony in Trump claiming unfair treatment of the American economy at a time when it was growing robustly while every other major economy had stalled or was losing growth momentum, Prasad remarked. In an even greater irony, the Trump tariffs are likely to end Americas remarkable run of success and crash the economy, job growth, and financial markets.

Despite Trump's assertions and those of his trade advisers, who argue that existing trading rules disadvantage the United States, mainstream economists challenge this perspective. They argue that Trump harbors a distorted view of global trade, particularly regarding a fixation on trade deficits, which they contend do not impede economic growth.

The administration claims that numerous countries erect unfair trade barriers to inhibit American exports and employ questionable tactics to gain an advantage for their own industries. In Trump's narrative, his tariffs represent a necessary reckoning: he portrays the U.S. as a victim of an economic assault perpetrated by nations such as Europe, China, Mexico, Japan, and even Canada. While it is true that some nations impose higher taxes on imports than the U.S., and some manipulate their currencies to remain competitive, the United States remains the second-largest exporter globally, trailing only China. In 2023, the U.S. exported an impressive $3.1 trillion worth of goods and services, significantly surpassing Germany, the third-largest exporter, which accounted for $2 trillion.

The apprehension that Trump's solutions might prove far more harmful than the issues they aim to address has resulted in a mass exodus of investors from American stocks. Since Trump unveiled his comprehensive import tax strategy on April 2, the S&P 500 index has plummeted by 12%.

The Trump administration often cites Americas consistent trade deficits as evidence of foreign exploitation. The president has pledged to rectify these imbalances and revive millions of manufacturing jobs that have disappeared over the decades by implementing import taxes not seen since the era of horse-drawn carriages. Theyve taken so much of our wealth away from us, Trump asserted during a White House Rose Garden ceremony celebrating the tariff announcement. Were not going to let that happen. We truly can be very wealthy. We can be so much wealthier than any country.

However, it is essential to note that the United States is already the wealthiest major economy globally. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) had forecasted in January that the U.S. would outpace every other major advanced economy in growth for the year. While countries like China and India may have grown at a faster rate over the last decade, their living standards remain significantly lower than those in the U.S.

The decline of manufacturing in the U.S. has been a gradual process, with a consensus among analysts that many American manufacturers have struggled to compete with a surge of affordable imports following Chinas accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. This shift resulted in the closure of factories, mass layoffs, and the deterioration of communities across the heartland. By 2005, nearly 3 million manufacturing jobs had vanished, with automation and robotics likely playing a substantial role in this decline alongside the so-called China shock.

To combat this ongoing trend, Trump has consistently employed tariffs as his primary weapon. Since returning to the White House in January, he has implemented a slew of tariffs, including a 25% tax on foreign cars, as well as on steel and aluminum imports. His administration has targeted Chinese goods with a 20% tariff, in addition to previously imposed hefty tariffs on a wide array of Chinese imports. On April 2, he unleashed his most drastic measure yet: imposing 10% baseline tariffs on nearly all nations, with the expectation of reciprocal tariffs on those deemed as unfair actors, including countries as small as Lesotho, which faces a 50% tax, and China, which could see tariffs rise to 34% when combined with earlier taxes.

Trump perceives tariffs as a versatile economic remedy that will not only safeguard American industries and encourage domestic manufacturing but also augment revenue for the U.S. Treasury and provide leverage to influence other countries on issues extending beyond trade, such as drug trafficking and immigration. He often points to the persistent trade deficit, which has seen the United States consistently purchase more from other countries than it sells for the past fifty years. In 2024, the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services reached an astounding $918 billion, marking the second-highest total on record.

Trump's trade adviser, Peter Navarro, has labeled these trade deficits as the sum of all cheating by other nations. However, many economists caution against equating trade deficits with national weakness. Over the past five decades, the U.S. economy has nearly quadrupled in size when adjusted for inflation, despite these deficits.

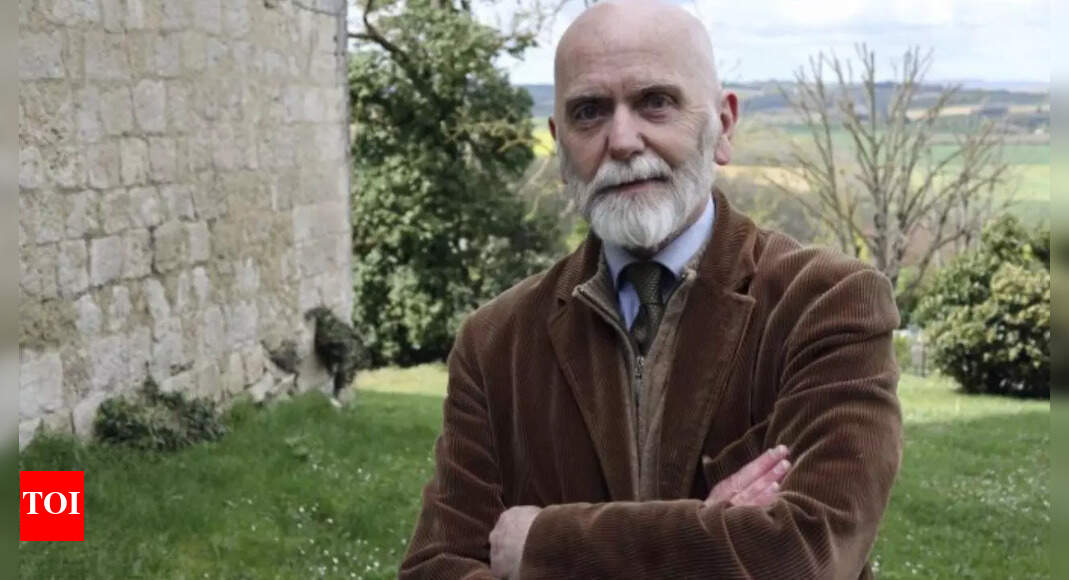

Former IMF chief economist Maurice Obstfeld, now a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, argues that a larger trade deficit does not necessarily correlate with lower growth rates. There is no reason to think that a bigger trade deficit means lower growth, he stated, further asserting that the opposite could often be true for many countries. Obstfeld emphasized that trade deficits do not mean a country is being exploited or losing out in trade.

Interestingly, the rapid growth of the U.S. economy often leads to increased imports, thereby widening the trade deficit. For instance, the trade deficit escalated to a record $945 billion in 2022 as the American economy rebounded from COVID-19 lockdowns. Typically, trade deficits contract considerably during recessions. It is also noteworthy that trade deficits are not primarily a result of unfair trading practices by foreign nations; rather, they stem from domestic factors, particularly the American tendency to save less and consume more than what is produced.

The renowned consumer culture in America, characterized by an inclination to spend beyond its means, results in a significant portion of this expenditure being directed toward imported goods. Economists argue that if the United States were to increase its savingsperhaps by curtailing its budget deficitsthis would, in turn, help ameliorate its trade deficit.

Jay Bryson, chief economist at Wells Fargo, remarked, Its not like the rest of the world has been ripping us off for decades; its because we dont save enough. The flipside of Americas low savings and persistent trade deficits is a steady influx of foreign investment, as other nations funnel their export earnings into the U.S. According to the World Bank, direct foreign investment into the United States reached $349 billion in 2023, nearly double that of Singapore, which ranked second in foreign investment inflows.

Some economists, like Barry Eichengreen from the University of California, Berkeley, warn that the only scenario in which tariffs could effectively reduce the U.S. trade deficit is if they lead to a collapse in domestic investmentan outcome that would spell disaster for the economy.

Harvard University economist Dani Rodrik believes that a well-designed industrial policy, supported by selective tariffs, could have fostered increased investment and capacity within the manufacturing sector. Instead, he argues, Trumps approach has created significant uncertainty and alienated the U.S. from its trading partners, leading to what he criticizes as a fundamentally flawed policy.

AP Economics Writer Christopher Rugaber contributed to this report.