Cameroonian Refugees Reflect on Trauma and Hope Amid Political Turmoil

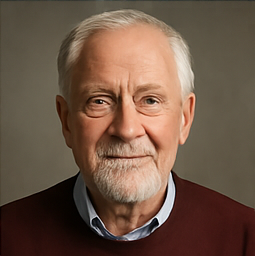

Amidst the lively sounds of children rehearsing for an upcoming drama performance, a local yam seller is heard calling out to passersby, enticing them with discounts for his goods. Just up the incline from this bustling scene, Solange Ndonga Tibesa sits outside a shuttered graphic design shop, sharing her harrowing story of being forcibly uprooted from her homeland in north-west Cameroon.

Back in June 2019, Solange, accompanied by her three-month-old baby, was kidnapped by secessionists who accused them of supporting the military. Her captors subjected them to relentless physical assaults, striking them with the butts of their weapons, and forced them to endure a harrowing two-day ordeal in the depths of a forest, deprived of food and water.

We remained hidden in the forest for two days. My baby cried incessantly, and we eventually grew accustomed to the incessant buzz of mosquitoes biting us, recounted the 30-year-old Tibesa. One of the captors demanded that I remove my clothing, but I pleaded with him, saying: It would be preferable for you to kill me than to violate me, which prompted some of the others to intervene.

As Cameroon prepares for its upcoming elections in October, the political landscape is tense. President Paul Biya, who has held power since 1982, is seeking an unprecedented eighth term in office. With an estimated 6.9 million citizens registered to vote, the election carries significant implications for the nation. Unfortunately, individuals like Tibesa, who sought refuge in Nigerias Cross River state following her release, are among the thousands who find themselves unable to participate in the electoral process despite their desire to do so.

The border region between Nigeria and Cameroon is heavily impacted by ongoing conflict; much of Nigeria's eastern region shares its border with Cameroon. This area has become a pathway for two overlapping migratory crises. In the northern sector, Nigerians flee the violence perpetrated by jihadist groups such as Boko Haram, while in the southern sector, Cameroonians escape a civil war that has plagued their English-speaking regions since 2017.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), approximately 107,000 Cameroonian refugees have crossed into Nigeria, with around half of that number residing in and around Adagom, Cross River state. The Nigerian government has allocated 63 hectares (about 156 acres) of land to accommodate these displaced individuals, who live in open settlements. The UNHCR provides monthly stipends to households in these communities and offers skills training to help them build sustainable lives.

Despite the challenges they face, many Cameroonian refugees have managed to integrate into their Nigerian host communities. They engage in cultural exchanges, with some marrying locals and passionately debating the outcomes of football matches. The linguistic similarities between the dialects of pidgin English and Ejagham spoken on both sides of the border have facilitated this integration, allowing refugees like Tibesa to move past their traumatic experiences and strive for a brighter future.

Tibesa has taken on numerous roles within her community: she coaches a netball team, volunteers as a social worker, and has enrolled in courses focused on biofuel production and plastics recycling, aiming to contribute positively to her surroundings. Meanwhile, Tessy Ekpang, 29, who lost two uncles to military violence, is excitedly preparing to move to Kenya later this month to pursue a pharmacy degree on a fully funded scholarship.

In close proximity, an agricultural engineer named Edmund is putting his skills to use by constructing solar power systems next to his fish pond, which currently houses 3,000 fingerlings, all made possible by land purchased from the Adagom community.

The historical context of Cameroon adds depth to the current crisis. The land that now constitutes Cameroon was divided and reconfigured by European colonial powers in the 19th and 20th centuries, often without consideration for the peoples living there. A century ago, the entire territory was known as the German colony of Kamerun.

Following World War I, the territory was partitioned between British and French administrations. A 1961 plebiscite saw the southern region of Cameroons rejoining Cameroon, while the northern region aligned with Nigeria. Today, Cameroon is predominantly Francophone, yet it retains two English-speaking regions in the west, where grievances have long been voiced regarding their treatment as second-class citizens.

The situation deteriorated dramatically in 2016 when peaceful protests against the imposition of French-speaking judges and teachers in the English-speaking areas were met with military force. Armed groups, referred to as the Amba Boys, emerged in response, declaring a breakaway republic named Ambazonia.

The ramifications for the civilian population have been catastrophic. Schools have been shuttered, bridges destroyed, and an estimated 4,000 civilians have lost their lives, with at least 712,000 displaced both within and outside the country. Not a single person remains in my village, lamented Ekpang.

Aid organizations estimate that half of the 4 million people living in the affected regions require humanitarian assistance, and recent changes to foreign aid could further complicate support efforts.

In 2024, the United States funded a significant portion of the UNHCRs budget in Nigeria. We are gravely concerned by the widening gap between needs and available resources, and the profound impact that funding cuts will have on millions displaced by conflict and persecution, cautioned Alpha Seydi Ba, a UNHCR representative based in Dakar.

Many analysts suggest that the ongoing conflict persists due to the governments reluctance to decentralize power or engage in constructive dialogue with separatists, whom they label as terrorists. Reports from Human Rights Watch indicate that many young men suspected of supporting the separatist cause have faced detention.

A national dialogue convened in 2019 by Biya's administration ultimately failed, as key separatist factions were excluded from the discussions. Efforts by Canada and Switzerland to mediate the crisis have also yielded minimal results.

With the election on the horizon, its outcome could have significant implications for the future of peace in Cameroon. Should Biya secure another term, as many expect, a continuation of the status quo is likely. If health concerns prevent him from running, there are rumors that he may appoint his 53-year-old son, Franck Biya, as his successor.

Experts insist that regardless of the election's result, there must be renewed efforts toward dialogue. Cameroons international allies should advocate for an inclusive dialogue to resume, emphasizing the necessity for improved governance and accelerated decentralization, so that the anglophone regions can realize the autonomy their special status was meant to provide, urged Hubert Kinkoh, a researcher with the Institute for Security Studies in Addis Ababa.

For the refugees in Adagom, time is of the essence, and the toll of their losses continues to mount. Tibesa expresses a deep yearning to return to her homeland. Despite everything, I love my country. Yet, when I come across images of the victims, I cannot help but break down in tears. Nobody is safe back home. If you turn to the army for help, the Amba Boys will chase you, and if you appeal to the Amba Boys, the army will follow, she shared, encapsulating the desperate plight faced by many.