True blue: why the chore jacket just won’t quit

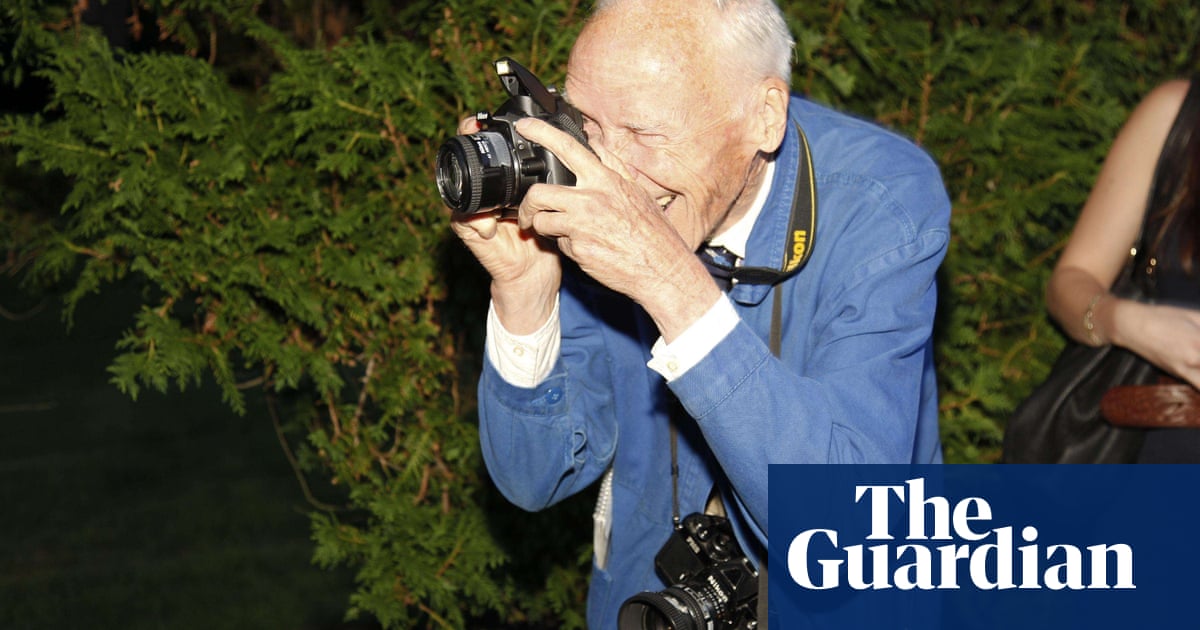

Look around you and before too long you are likely to spot a chore jacket. I saw a particularly fine example on a dad last weekend at a heritage railway. As warm days stretch into still-cold evenings, beer gardens are full of them. They are worn down allotments and in towns, and I have a few in my own wardrobe. Because what began as everyday workwear for French factory employees more than a century ago has today become a wardrobe stalwart. You can even find chore jackets in the supermarket, with Sainsbury’s Tu and Asda’s George offering the cheapest – the simple design lends itself to mass production. The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more. They march across my Instagram feed, from workwear-inspired brands LF Markey, Folk or Uskees, down through high street stores such as Zara and John Lewis, as well as at hyper-expensive label The Row – your French machinist might have muttered a piquant “dis donc!” at its chore, with pockets too close together and a £1,500 price tag. The jacket has been worn by the likes of Brooklyn Beckham and Hailey Bieber, while Harry Styles is often seen in a version by SS Daley, the label inspired by British class tensions (and in which he has a financial stake). View image in fullscreen A different take on blue-collar … Harry Styles in London earlier this month. Photograph: Neil Mockford/GC Images So how did we get here? Traditional homeware store Labour and Wait started selling a jacket by old-school French brand Mont St Michel when it opened in 2000. But the coat arguably found its way to contemporary fashion through New York street style photographer Bill Cunningham, who wore one like a uniform as anyone who watched a 2010 documentary about his life and work well knows. Monty Don embraced its functional origins by wearing one in the garden, even inspiring a Reddit thread where contributors ask “how can I dress like Monty Don?”. On the shoulders of these practical and creative men, the chore coat evolved from its utilitarian origins. Other designers have since gone rogue with the classic style, with mixed results: the Tate is selling a chore made in collaboration with London streetwear brand Lazy Oaf, in bright indigo with garish embroidered details. Adidas’s “chore” is a burgundy jacket with the sportswear brand’s logo on the back, fastened with zips and Velcro. It is absolutely hideous. Even brewers are getting in on it, with Guinness launching a collab with Native Denims: its off-white body with dark buttons is perhaps supposed to reflect the colouring of their fiendishly popular pints, but instead looks like white fabric that has been washed with black socks. View image in fullscreen Well worn … a vintage chore jacket stocked by the French Workwear Company. Many of these outliers are far from the original. So what is a true chore? I thought I had two, both vintage: a blue cotton jacket and a heavy brown canvas railway worker’s coat with a Peter Pan collar. Apparently not, according to Marie Remy of The French Workwear Company, who has been selling the coats since 2014. Her father, a mechanic, wore the bleu de travail (as they’re known in her homeland) to work six days a week. Remy is a purist and for her, the bleu has to be made from blue cotton twill or moleskin and have three patch pockets: two large ones and a smaller one higher on the breast. It should “absolutely not” have a lapel collar (like mine) but rise up to the neck with four, five or, at a push, six buttons. The jacket’s roomy, boxy shape makes it both practical in the workplace (there’s no loose material to get caught in machinery) and adaptable in style. “If you got a child to draw a jacket, it would be almost like workwear in how it’s pared down,” says Remy. “That’s why I think it survived so long.” An expert in the history of the coats, she explains that they took off after the first world war, when the rapid industrialisation of France led to more factories, an employment boom and, significantly, collective bargaining power. The rights negotiated by French unions included free clothing for their workforce, with some men at companies such as SNCF or Gaz de France entitled to at least one new chore coat each year. This led to the overproduction that Remy believes explains why they remain so plentiful on the vintage market today. “In some sectors, the unions would even manage to negotiate the costs of washing the garments,” she says. “You have to think of the clothing as work tools, really.” skip past newsletter promotion Sign up to Fashion Statement Free weekly newsletter Style, with substance: what's really trending this week, a roundup of the best fashion journalism and your wardrobe dilemmas solved Enter your email address Sign up Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy . We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. after newsletter promotion View image in fullscreen ‘It’s like a backlash against fast fashion’ … an updated version by Toogood. Regular, often intensive, wear meant that each jacket became unique, taking on the imprint of its owner’s life and labour, and this has fed into their modern appeal. Fergus Henderson, co-founder of the London restaurant St John, is such a fan that he and business partner Trevor Gulliver collaborated on their own chore with Savile Row-based menswear brand Drakes. According to Gulliver, Henderson refers to his original French jacket “as his history, a sort of diary of days” – every crease or stain tells a story. He praises the chore for “durability, an everyman quality, and they are simply of sound design – they work”. But the popularity, or even the fetishisation, of workwear can be thorny. In the case of the chore, the modern middle class has plucked them from their historical context, while simultaneously enjoying the authenticity they signal by dint of their blue-collar origins. (After all, we get the term “blue collar” from workwear, since blue dye was the cheapest available for these mass-produced items.) The fact that they exist thanks to the hard-won rights of the early-20th-century French unions, and the graft of those who spent their entire working lives in them, arguably becomes a form of ironic appropriation if you’re wearing one to the local farmers’ market to drop a tenner on kimchi. Contemporary designers are aware they now signal a certain identity. “If you recognise yourself as somebody that doesn’t necessarily sit behind a desk, then the chore coat is for you,” says Erica Toogood, pattern cutter at the eponymous brand she founded with her sister Faye. The chore was a direct inspiration for their mechanic jacket, which remains a staple of the collection they launched in 2013. “One of the most beautiful things is the idea of the chore coat being for the anonymous worker, yet every one of those vintage jackets indicates the DNA of the person that’s worn it,” she says. Her challenge as a pattern cutter is to echo this sense of a personal history, even in a new garment. “We try to cut those elements in to show that maybe somebody has been in that jacket before you, and that you’re simply taking on the role of wearer as another person along the line.” View image in fullscreen Monty Don pairs the jacket with a scarf in his British Gardens series. Photograph: Alexandra Henderson/AHA Productions Remy believes that vintage chore coats remain popular because of their durability. “People are attracted to them because it’s like a backlash against fast fashion,” she says. “What can you do as an individual? It can feel overwhelming, it’s very difficult.” To her, buying a chore coat is “a mini standing up to it as an individual. It’s attached to values.” One sure-fire way contemporary designers can build positively on the jacket’s history is making new ones in larger sizes – we’ve all got a lot bigger since the early 20th century. This has been at the core of the Toogood philosophy, which as a unisex brand has a universal sizing range. Despite the abundance of chore coats on the market, familiarity doesn’t have to breed contempt. When the chore is done well, and doesn’t stray too far from the original model, it remains versatile and comfortable, whether a battered 60-year-old vintage jacket or a new, more expensive, long-term investment. For Toogood, “they become firm friends that stay in your wardrobe for years”.