Did scientists actually find the strongest evidence of alien life yet?

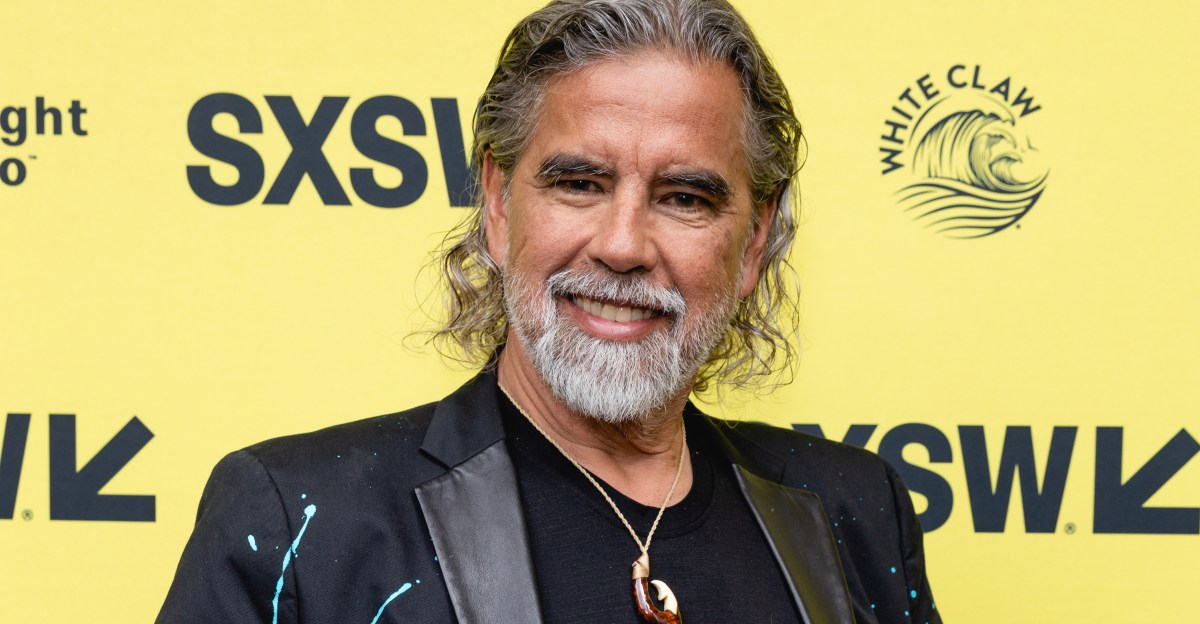

Open this photo in gallery: An artist's concept shows what exoplanet K2-18 b could look like based on science data.NASA, CSA, ESA, J. Olmsted (STScI), Science: N. Madhusudhan (Cambridge University)/via REUTERS When Nikku Madhusudhan, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Cambridge, addressed the world about his possible detection of life on another planet on Thursday, he started by reflecting on the larger import of the moment. How incredible, he said, that our species, which is descended from single-celled life forms that first emerged on this planet billions of years ago, has acquired the capability to find life elsewhere in the universe. “It’s a very human experience and we’re all in it as a species,” Dr. Madhusudhan said. Those who study exoplanets – planets beyond our own solar system – can agree that it’s amazing to be part of the first generation of scientists to have a realistic chance of spotting signs of extraterrestrial life. But many are making clear that Dr. Madhusudhan and his colleagues have not demonstrated that they’ve found any such thing on the planet designated K2-18 b. The skepticism goes beyond the question of whether the evidence presented makes a strong case for life. It is also about whether or not the evidence even exists. “Given the quotes I’m seeing in the press, this isn’t just a case of crying wolf, it’s akin to crying werewolf,” said Nicolas Cowan, an associate professor at McGill University who studies exoplanet atmospheres. The reaction underscores a longer term confidence, which many in the field share, that it’s only a matter of time before an alien ecosystem is discovered. But that confidence reveals why this week’s report is so unconvincing. The team led by Dr. Madhusudhan used the James Webb Space Telescope to observe K2-18 b, a planet detected by a NASA spacecraft a decade ago. The planet cannot be seen directly but its presence can be deduced because it repeatedly crosses in front of the star it orbits, temporarily blocking a small fraction of the star’s light. Open this photo in gallery: Astrophysicist Nikku Madhusudhan at the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge, England, in April, 2025.The Associated Press When the telescope is used to look at the star with an array of instruments it can detect molecules that emit light at specific wavelengths. Most of that light comes directly from the star, but the star’s contribution can then be subtracted to obtain a chemical reading of the atmosphere of K2-18 b. When Dr. Madhusudhan’s team did this, they saw a wiggle in their data that they interpret as caused by one or two chemicals – dimethyl sulfide and/or dimethyl disulfide. They note that on Earth, when these molecules occur naturally, it is always a byproduct of living – specifically marine phytoplankton. Therefore, they argue in a peer-reviewed paper published Wednesday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, they have detected “a possible biosignature” that indicates the presence of life in an alien sea. This fits the notion of a “hycean” world — a term that Dr. Madhusudhan coined in earlier work to describe an ocean planet that primarily consists of water with a hydrogen atmosphere. A key detail is that K2-18 b sits within the “habitable zone” of its solar system. It lies at just the right distance from its star that, given other necessary conditions, it’s possible for water to exist there in liquid form. In their paper, the team is cautious about positing aliens as an explanation for their data. A press release issued from the university the next day used bolder language, announcing the “strongest hints yet of biological activity outside the solar system”. That was enough to invite widespread media coverage that mostly downplayed the caveats associated with the announcement. In his public talk, which was live-streamed as a news event, Dr. Madhusudhan further amplified the message, declaring that the only scenario that currently explains the data is one in which the planet is “teeming with life.” Unstated was the wide open door left for researchers to find other ways that the telltale molecules could plausibly occur without resorting to life. But many are betting this will not be necessary. What news reports have largely overlooked is the degree to which the detection depends on the method the team chose to extract a signal from their raw data. Other ways of working with the same data can lead to an answer that does not require the presence of dimethyl sulfide or dimethyl disulfide. Dr. Madhusudhan has made similar claims before and received similar pushback. “A big criticism of this group in the past is that you can explain this away with just a little bit of tweaking of your data reduction,” said Ryan Cloutier, an astronomer and assistant professor at McMaster University who was among those to determine the mass of K2-18 b following its initial discovery. Sara Seager, a Canadian-American astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute who helped to pioneer the theoretical study of exoplanets, said the idea that K2-18 b is an ocean planet also remains a very big assumption. “This particular planet has to have a lot of light gasses because it’s so big for its mass,” Dr. Seager said. “So it has to have a lot of hydrogen for sure. But what’s underneath that hydrogen? Is it a hot water ocean or is it hot liquid rock? That’s what we don’t know.” In a review paper about prospects for detecting life on exoplanets using JWST, posted online on Thursday, Dr. Seager calls the announcement from the Cambridge group “a problematic start” because it fails all three criteria that she suggests are necessary to characterize what is happening in the atmosphere of an exoplanet. The criteria include: an unambiguous detection of a particular feature in the data; high confidence that this can be attributed to a particular molecule; an interpretation that fits with all other data from the planet and that also rules out false positives. But given the ability that JWST and other planned spacecraft possess to sample the atmospheres or other worlds, Dr. Seager agrees that it’s likely more such announcements are coming, possibly with varying degrees of certainty about what has been found. Stan Metchev, who holds a Canada Research Chair in exoplanets at Western University, said he is skeptical about the new finding, but not about where the field is heading. “I’m cautiously optimistic about the prospects of finding life in the next 10 years,” he said. “We’re basically already probing the boundaries of what James Webb can tell us, improving our methodology, improving our ability to assess what is a possible, and this report is very much part of this process.”