Guinea's Only Private Drug Rehabilitation Clinic Battles Rising Drug Crisis

In Guinea, a country grappling with a burgeoning drug crisis, Dr. Marie Koumbassa and her dedicated team of 15 volunteers at the SAJED-Guine clinic are fighting a battle they believe is critical to the nations future. Their commitment is so profound that they offer their services without any pay, motivated by a sense of urgency regarding the escalating drug use among the youth.

Situated in the working-class neighborhood of Dabompa in Conakry, the clinic provides a haven for individuals struggling with addiction. Each week, the clinic receives numerous distress calls from family members of addicts, seeking assistance for their loved ones. The clinic is a part of a larger initiative known as the Service for Helping Young People in Difficult Situations due to Drugs, and its impact on the community is significant.

In the wealthier districts of Conakry, cocaine has emerged as the drug of choice. However, in other areas, substances like tramadol and crack cocaine are more prevalent, alongside a disturbing new trend involving a dangerous concoction known as 'kush.' This lethal mix includes cannabis, fentanyl, tramadol, formaldehyde, and, alarmingly, reports suggest the inclusion of ground human bones. Users of kush have been known to experience severe physical reactions, including sudden collapses, self-harm, and even fatalities.

Dr. Koumbassa recounted troubling stories of individuals who had been misled to believe that kush would enhance their cognitive abilities. People come here from the madrasa [Islamic schools] and tell us that scholars told them: Take this, you will read well and quickly learn, she shared. It actually destroys them. This misguided belief has contributed to the growing popularity of kush, which emerged in Conakry last March and has now infiltrated nightlife scenes, where patrons are mixing it into shisha pots.

Unlike its neighbors, Guinea Bissau and Sierra Leone, which have gained notoriety for drug trafficking, Guinea's more conservative social structure has typically been less associated with drug use. However, experts warn that a crisis is brewing, driven by the activities of cross-border trafficking syndicates. Kars de Bruijne, a senior research fellow at the Dutch thinktank Clingendael, noted the intricate relationship between criminal organizations operating across borders. The gangs in Sierra Leone have always moved to Guinea [when necessary], he explained. When gang members needed to evade law enforcement, they often found refuge in Guinea.

Moreover, the illicit trade is not just a one-way street; it involves the transfer of drugs from Guinea to Sierra Leone, indicating a well-established informal market. According to a report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), at least 5.6 tonnes of cocaine were seized off the Guinean coast between January 2019 and June 2024. In a striking incident earlier this year, Guinean authorities discovered seven suitcases filled with suspected cocaine in a vehicle owned by the Sierra Leonean embassy, highlighting the alarming extent of drug trafficking in the region.

Staff at SAJED-Guine acknowledge the critical lack of public knowledge regarding addiction treatment options. Despite these challenges, the nonprofit has successfully managed over 500 cases since its inception in 2019, when Dr. Koumbassa established the facility after attending workshops for psychologists in Abuja and Accra. We have patients who come from everywhere, from within the country, as well as students returning from places like America and France, said Yamoussa Bangoura, the clinics head of psychotherapy. The organization aspires to expand its outreach to other regions, including Bok, which is close to Guinea-Bissau, but financial limitations hinder their efforts.

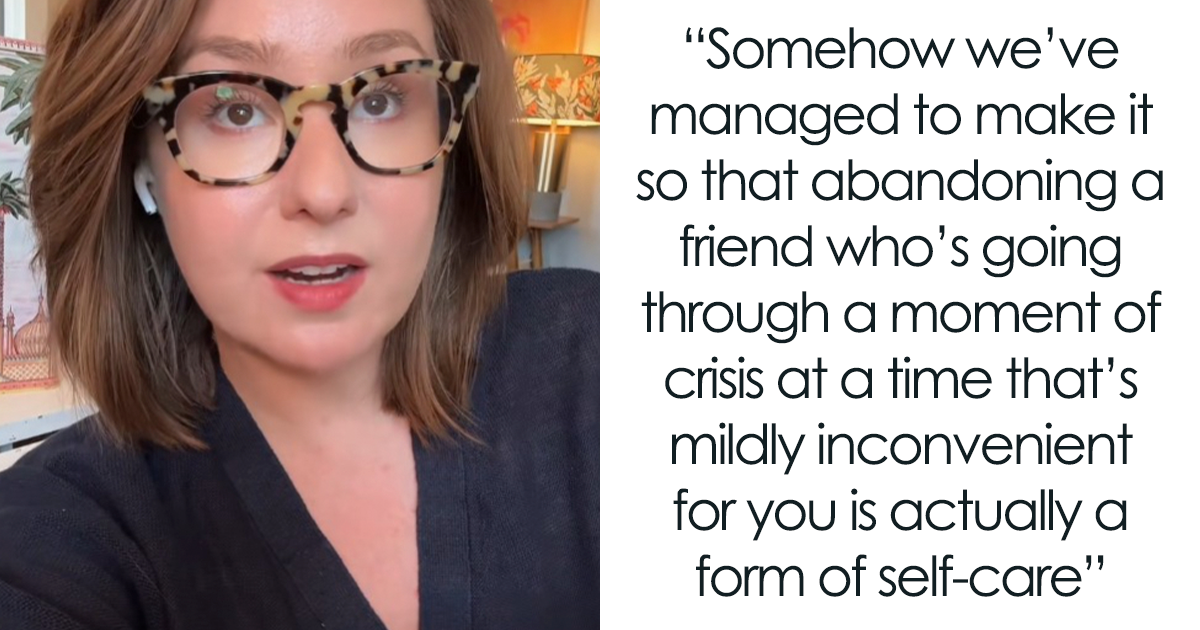

The crisis in Guinea can be attributed to a variety of factors, including widespread poverty and porous borders that facilitate drug trafficking. Some social workers believe that individuals protesting against the military junta that seized power in a coup in 2020 resorted to drugs to bolster their courage during demonstrations. Others argue that the juntas singular focus on maintaining power has caused it to neglect essential state functions.

The scale of drug abuse has overwhelmed Guinea's limited resources for treating addiction, with only two state-run facilities available for those in need. During the Covid-19 pandemic, one of these centers was temporarily closed, exacerbating the overcrowding at the other location. In contrast, SAJED-Guine has its own set of constraints; it can accommodate around a dozen patients at any given time.

The clinic primarily relies on its dedicated staff for funding, supplemented by small grants from private donors and revenue generated from the sale of fruits grown within the compound. Patients also assist with the upkeep of these plants, which keeps them engaged and fosters a sense of responsibility. Additionally, the sale of treatment medications contributes to the clinic's finances; however, due to the economic conditions of most patients, the facility often provides medications free of charge.

Located in a rented building from a member of the Guinean diaspora at a significantly reduced rate, the compound consists of a single-storey structure with cubicles that serve multiple purposes: a kitchen, laboratory, and pharmacy. It also includes a small emergency room and separate bedrooms for men and women, along with a common area with a television.

Bangoura noted that the appearance of the building often deters potential patients from seeking help. At the clinic, individuals suffering from alcohol addiction and depression are also welcomed. One resident, Diallo Mahmoud, a 32-year-old man whose struggles with alcohol began in his teenage years, found himself drawn to drinking while looking for work in cities like Abidjan and Brazzaville. His breaking point came after an altercation at a nightclub led to a violent incident, prompting his family to seek help from SAJED.

Now, as he and other patients share stories and support one another, Mahmoud talks about his aspirations for a renewed life post-rehabilitation. After I leave here, Ill not drink again, and Ill preach that to people, he declares, embodying the hope that drives both the patients and staff at the clinic.

As Dr. Koumbassa reflected on the broader implications of drug use in society, she emphasized the urgency of their mission. We have come to understand that drug consumption is recurrent in our homes, and the layer it consumes the most is the youth, the future of the nation, she stated. If we dont help them get out of it, it will be a problem for the nation.