Switzerland is home to Europe’s only psychedelics treatment

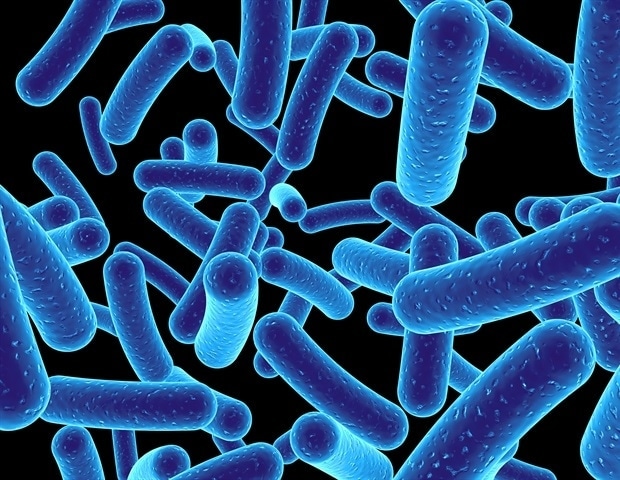

Switzerland is home to Europe’s only psychedelics treatment The psilocybin compound found in magic mushrooms is used at the Geneva University Hospital to treat depression. AFP Listen to the article Listening the article Toggle language selector Select your language Close English (US) English (British) Generated with artificial intelligence. Close Share With one in three psychiatry patients not responding to treatment with anti-depressants, doctors at Swiss hospitals and private practices are turning to alternative methods such as psychedelics. But the therapies are still costly, rare and sometimes informal. 8 minutes Aylin Elçi From innovative treatments to unequal access to medicine, I cover health topics and keep an eye on Switzerland's Health Valley. I'm Swiss-Turkish, and have a background in communications, journalism and photography. Before joining SWI swissinfo.ch, I covered technology and health at Euronews, and my work has been featured in international outlets including Fayn Press, Mediapart, Le Temps and Times of Malta. After spending a decade on anti-depressants, 45-year-old Jonathan Crespo from western Switzerland says he reached an all-time low when he began contemplating suicide. That’s what triggered his curiosity for alternatives to medication. “Four years ago, my therapist suggested I try electro-convulsion therapy in canton Vaud. That really scared me and got me to doing some research,” he explains. + Electric touch: neurostimulation’s comeback in psychiatry Crespo stumbled on a reportage on the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) and their use of psychedelics to treat patients, including lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), one of the most potent psychedelic drugs, and psilocybin, a variety of psycho-active mushrooms. Shortly after, he began a two-and-a-half-year therapy using the two drugs and MDMA, a stimulant sometimes known as ecstasy. After three sessions, he stopped taking his medication and drinking alcohol, lost weight, “reintegrated” his body and step by step “began feeling [emotions] again”. Between six and ten other patients were attending each session and going through the same shifts as him, but besides them, no one could really understand what it was like to undergo psychedelics-assisted psychotherapy. “Patients often say, ‘my husband or my wife can’t understand what I’m living through’. People think we’re a bit crazy,” Crespo says. That’s why he co-founded Psychedélos, an association dedicated to the well-being of patients and the de-stigmatisation of substances once associated with the United States counterculture movement and the club scene. Read more about the history of psychiatry and how Switzerland contributed: More More From Jung to psychedelics: a timeline of Switzerland’s contributions to psychiatry This content was published on From the synthesisation of LSD to the commercialisation of antidepressants, Switzerland has played a key role in the understanding and treatment of psychiatry. Read more: From Jung to psychedelics: a timeline of Switzerland’s contributions to psychiatry “We were the first patient circle in the world fighting for the use of psychedelics with psychotherapy. This isn’t about recreational psychedelics – it’s really a different approach”, says Crespo. A unique legal framework The use of LSD, MDMA, and psilocybin in medicine has been legal in Switzerland since 2014, both for research and for the treatment of conditions such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety. While they are not approved as medication, doctors wishing to treat a patient with psychedelics can apply for individual approval from the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) and obtain “exceptional authorisation”. This legal framework has put the country at the forefront of psychedelics therapy, alongside the US, Canada and Australia. But only Swiss residents can follow these treatments in Switzerland, and they are required to follow psychotherapy sessions together with their psychedelics intake. External Content Gabriel Thorens, a psychiatrist in addictology at HUG, says any medical specialist can make the request to the FOPH. Colleagues interested in psychedelics regularly reach out to him, and his team has been dealing with “more requests than possible”. The hospital organises five to ten sessions each week, and has treated 300 patients since the programme’s launch in 2019. Nonetheless the treatment remains niche, with the majority of patients suffering from mental-health conditions still taking anti-depressants. In Europe, consumption of anti-depressants more than doubled between 2000 and 2020, with an average of 75.3 daily doses of medication per 1,000 people in 2020. In Switzerland, about 770,000 people, or 9% of the population, was on anti-depressants in 2021. Meanwhile, only 686 people followed a psychedelics-assisted therapy in 2024, with treatment options limited to a handful of private clinics, the university clinics of Bern, Zurich, Fribourg and the HUG, where patients currently have to wait six months to a year for access. Little access Treatments are time-consuming and expensive. Nurses observe individuals for sessions that can last up to eight hours, and follow-up psychotherapy sessions take place the day following intake. Some insurance policies cover the surveillance and the therapy part of the treatment, but the drugs are entirely paid for by patients. At HUG, one session of LSD therapy costs CHF200-300 ($246-370), while psilocybin starts at CHF400 and can reach CHF800 for high doses. Sessions are repeated about three times a year. Registration as medication would be a step towards reimbursement. But in the US, which has historically set the tone for medical approval in the rest of the world, the Food and Drugs Administration last summer rejected a request for MDMA-assisted therapy in order to allow the company in question to “further study the safety and efficacy” of the drug. “We must continue to prove that these treatments are at least as effective as anti-depressants. But one key issue remains the registration of substances as official medicine,” says Thorens. + Is psychedelic therapy about to go mainstream? Additionally, given the difficulty of prescribing these drugs for home use, and the impossibility of patenting molecules that are free of intellectual property – either because they were discovered a long time ago or are naturally occurring – commercialisation is slow. Johnson & Johnson was able to sell ketamine, an anaesthetic with psychoactive effects under the name Spravato. The process to commercialise the drug was complex as ketamine can no longer be patented since it was discovered over 60 years ago. The company had to patent a part of a molecular entity (esketamine), specify what it would treat (depression), what dosage to take (56mg or 84mg), and the means of intake (nasal spray). The drug is currently available in 77 countries including the US, member states of the European Union, Australia and Switzerland. While ketamine does not act on the same receptors as psychedelics like LSD, its hallucinogenic effects at higher doses means it’s often considered an “atypical” one. The treatment is also recognised by Swissmedic, the national body responsible for authorising drugs, which describes it as a “new treatment option” for people suffering from a depressive disorder or bipolar disorder and who are at risk of suicide. ‘Just enjoy it’ Bipolar disorder and suicidal thoughts were exactly what Tom, who is on the autism spectrum, was suffering from until he was proposed ketamine at a clinic in Meiringen, in canton Bern. Back in 2023, every Monday, Wednesday and Friday after lunch over a three-week period, he sprayed about five hits up his nose on a bed assigned to him. The lack of other instructions puzzled him. “The crazy thing is that nobody told me at all what I should do while on ketamine. Doctors mostly said to just enjoy it,” recalls the 34-year-old patient. He says the therapy only worked because he put “personal effort” into asking doctors a series of questions between sessions, and trying to reconnect with his inner child during his trips, instead of “just being high”. Tales of unregulated intakeExternal link have been circulating in Switzerland, and the country’s main professional body for psychiatrists released treatment recommendationsExternal link for psychedelics therapy, which it said integrated recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association and the Royal Australian and Zealand College of Psychiatrists. “As psychedelic therapy differs from previously available pharmacological treatment methods in psychiatry, it places particularly high demands on doctors in terms of indication, information, implementation and documentation, as well as dealing with regulatory and ethical issues,” reads the Swiss Society of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy document, released in May 2024. As the framework for psychedelics therapy continues to evolve, the target is really patients’ needs, says Thorens: “At the end of the day, what’s most important is to have the best possible treatment for the best possible indication.” Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw More Debate Hosted by: Aylin Elçi How are mental illnesses treated in your country? In Switzerland more people are being referred to electrical therapies or psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Are there similar approaches where you live? Join the discussion View the discussion In compliance with the JTI standards More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative