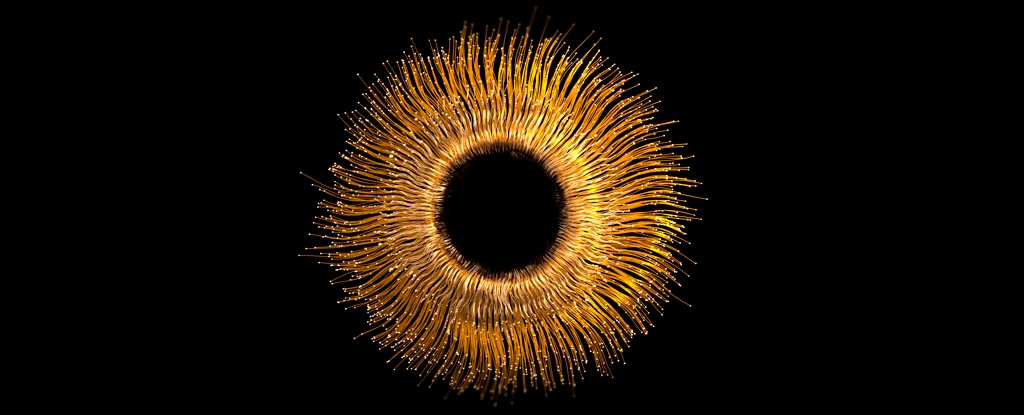

Gold Injections in The Eye May Be The Future of Vision Preservation

Gold dust in eyes might seem like an unusual therapy – but a new mouse study in the US shows the approach could potentially treat age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other eye problems. Macular degeneration affects millions worldwide and becomes more likely as we age. Damage to the macula, located in the retina and containing light-sensitive photoreceptor cells, causes blurring and other vision issues. While there are treatments available to slow the progression of AMD, they don't reverse it. "This is a new type of retinal prosthesis that has the potential to restore vision lost to retinal degeneration without requiring any kind of complicated surgery or genetic modification," says biomedical engineer Jiarui Nie, from Brown University in Rhode Island. "We believe this technique could potentially transform treatment paradigms for retinal degenerative conditions." Here's how the new treatment works: very fine gold nanoparticles, thousands of times thinner than a human hair, are laced with antibodies to target specific eye cells. They're then injected into the gel-filled vitreous chamber between the retina and the lens. Next, a small infrared laser device is used to excite these nanoparticles and activate specific cells in the same way photoreceptors do. If the treatment makes it to us humans as well, that laser could be embedded in a pair of glasses. In the mice this was tested on, engineered to have retinal disorders, the treatment method was effective at restoring vision, at least partly (it's tricky to give a mouse a full eye test). It showed the nanoparticles could help bypass damaged photoreceptors. "We showed that the nanoparticles can stay in the retina for months with no major toxicity," says Nie. "And we showed that they can successfully stimulate the visual system. That's very encouraging for future applications." The approach has similarities to existing treatments for AMD and related conditions such as retinitis pigmentosa. However, this new method is less invasive, with no surgery or large implants inside the eye needed, and also promises to cover a wider field of vision. As with most studies in mice, there's a good chance the findings will translate over to humans, but it'll take a while to get there – and to get something safe that can be approved for use. This is an important first step. An increasing number of studies are presenting ways in which eye diseases could be tackled by the latest technology and science, including reprogramming other retinal cells to replace photoreceptors that are no longer working. "This innovation marks a significant breakthrough, setting the stage for future development of photothermal retinal prostheses such as wearable goggles," write the researchers in their published paper. "For future human applications, further refinement is necessary." The research has been published in ACS Nano.