Ancient Christian community works to rebuild

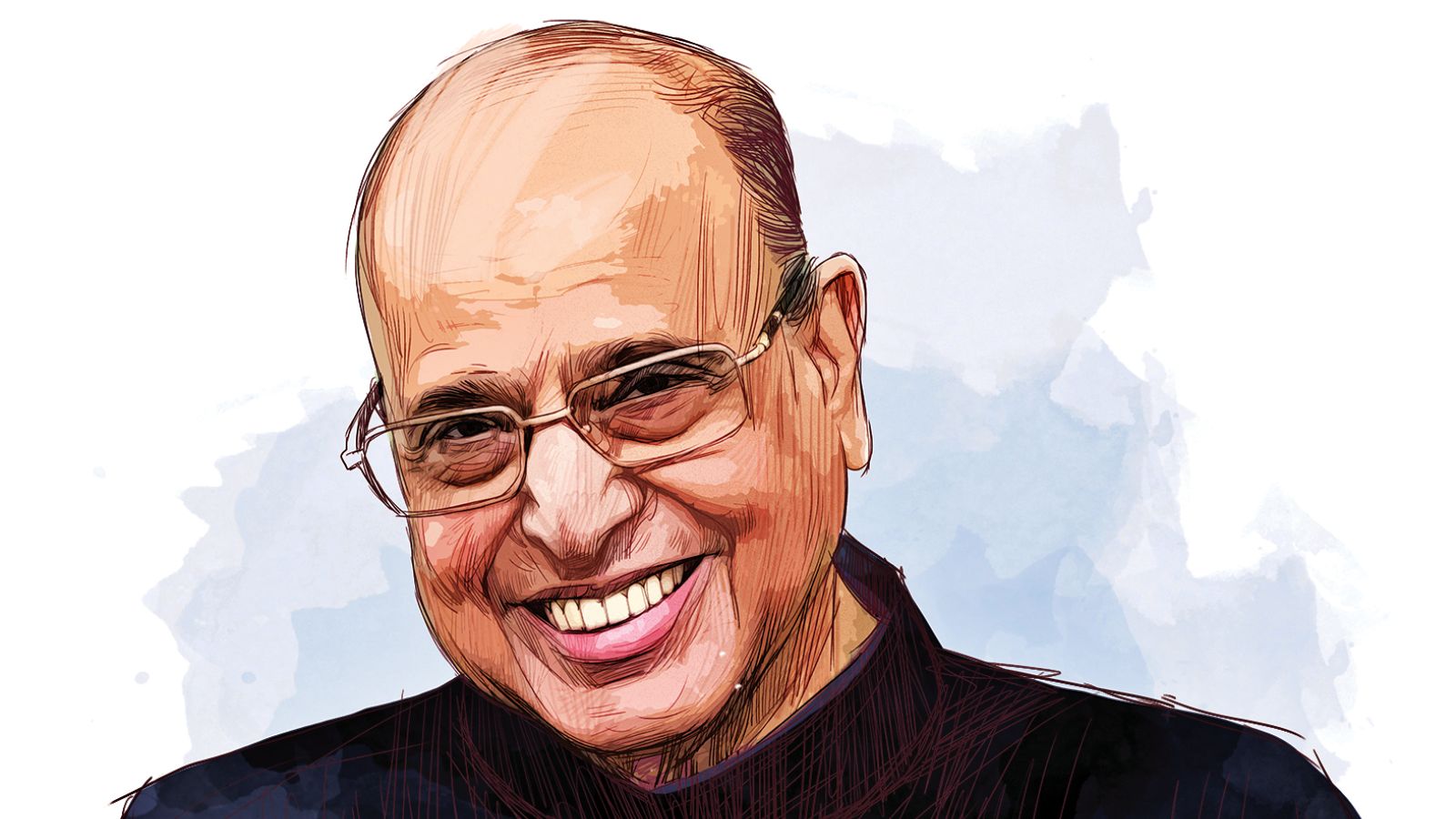

ALEPPO, Syria - It’s been four months since the fall of longtime dictator Bashar al-Assad marked the beginning of a new era in Syria. While the strongman’s toppling has brought hope, incidents of sectarian violence - like the ones that tore through Syria’s coast last month - have increased fears that the country’s ethnic and religious minorities could be targeted. Despite this, some of the members of Syria’s oldest Christian communities say they feel as welcome as ever, and are already working together with their neighbours - and the new authorities - to rebuild their devastated country. Situated in Syria’s north, the city of Aleppo is one of the world’s oldest, with a history stretching back thousands of years. Famously cosmopolitan, Aleppo has hosted a large Christian community for almost as long as the religion has existed. Included in this is one of the city’s most distinctive groups: its Armenian population. Zarmik Boghikian is the editor-in-chief of Kantsasar, a weekly publication that is Aleppo’s only Armenian-language newspaper. Aleppo Zarmik Boghikian is the editor-in-chief of Kantsasar, a weekly publication that is Aleppo’s only Armenian-language newspaper. (Neil Hauer) She has spent all of her 54 years in Aleppo - including through the five years of full-scale warfare that engulfed the city from 2012 through 2016. ‘Most difficult period of my life’ “I remember the first bombing in Aleppo, in February 2012,” Boghikian says. “It killed several people, including one Armenian. The fighting picked up in the countryside over the next few months, and the full battle here started in July. It was the most difficult period of my life,” she says. The battle for Aleppo would mark the fulcrum of the Syrian civil war, as both rebels and Assad’s regime struggled for control of the city. Much of the city’s east and south, held by rebels and targeted by both Assad’s and Russia’s air forces, was reduced to ashes. The main Armenian-inhabited neighbourhoods were spared the heaviest fighting, but did not escape unscathed. “We (Armenians) were between two sides, not wanting to fight for Assad or the opposition,” Boghikian says. “The community formed some local militias to defend our churches and schools, but mostly tried to stay out of it as much as possible. Some of our young men were conscripted by the regime and forced into the army, but we were luckier than many others,” she admits. Aleppo Armenian community's Holy Trinity Church in Aleppo, Syria. (Neil Hauer) By the time the battle for the city ended in victory for Assad’s forces in December 2016, Aleppo was a shell of its former self. Heavily depopulated by the fighting, the survivors were left to pick up the pieces and continue on. Aleppo’s Armenian population, like other communities, dwindled as a result: while there were perhaps 70,000 Armenians in the city before the war, Boghikian estimates there are “maybe 20-25,000” left today. But despite it all, the community persevered. In neighbourhoods like Aziziyeh, Jdeydeh and Midan, the Armenian community is highly visible. Shops bearing names in both Armenian and Arabic abound; handsome Armenian churches adorn a number of the area’s most prominent thoroughfares. Aleppo An Armenian doctor's office in Aleppo, Syria. (Neil Hauer) While much of Aleppo’s present-day Armenian community are the descendants of survivors of the Armenian Genocide - the systematic destruction of the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian community in 1915 - their historic presence goes back centuries further. Standing testament to this is the Forty Martyrs Cathedral, a 15th-century Armenian church located inside Aleppo’s famed Old City. Clad in the traditional black robes of an Armenian Apostolic priest, Father Garnik, one of the cathedral’s preachers, gives his views on the recent past. ‘Looking to the future’ “Aleppo has had many chapters in its history, both good and bad,” he says. “Our church stayed open throughout all of them; we didn’t miss even one service during the last war. Now we are past this hard period and looking to the future,” Father Garnik says. The end of the Assad era came swiftly in Aleppo. Just three days after launching their offensive last fall, Syrian rebels - led by Ahmad al-Sharaa, now Syria’s president - captured the city on November 30. While the early days were uncertain and chaotic, life quickly resumed as more or less normal. The background of Syria’s new rulers, including al-Sharaa - once the head of al Qaeda’s branch in Syria - brought serious concerns that hardline Islamists would target minority groups such as Christians. Recent weeks have not helped matters. In early March, Syria experienced its worst violence since Assad’s exit. An uprising by pro-Assad elements on the Syrian coast led to four days of bloody reprisals against members of the Alawite sect, the minority group from which the Assad family and much of the former regime’s elite hailed. Sunni militiamen allied to the new government carried out summary executions of Alawite civilians, going door-to-door in coastal villages in a harrowing campaign. The Syrian Network for Human Rights, a leading watchdog organization, says that more than 1,600 people were killed between March 6 and 10. Amidst the anti-Alawite violence, rumours spread that Syria’s Christians had also been attacked. It later emerged that these reports were unfounded. Both international aid organizations and local Christians themselves said that, while some Christians were caught in the crossfire, no targeted killings of Christians took place. Armenians in Aleppo also say that no oppression against them has yet occurred. “We have had no issues with the new authorities whatsoever,” says Jirair Reisian, a well-known conductor and former member of Syria’s parliament. “Arabs in general have always been kind to Armenians - they helped us survive during the genocide. There is great respect for the Armenian community here,” he says. Far from targeted repressions, Syria’s new authorities have taken measures to build trust with the Armenian community in Aleppo. Damascus’s General Security forces have adopted the habit of taking local Armenians with them as they patrol the Armenian-populated neighbourhoods, helping both sides to familiarize with one another and allay concerns. ‘We are all Syrian’ The mere idea that the Armenian community could suddenly fall victim to religiously motivated harassment from Muslim Syrians is met with bewilderment. “To be honest, I don’t understand all these Western politicians who are coming to Syria and demanding special rights for minorities,” Reisian says. “We are all Syrian, whether Armenian or Arab, Christian or Muslim. I only need the same rights as everyone else,” he says. Boghikian echoes these sentiments. “Of course there are problems here - there is crime, there isn’t enough electricity, salaries are low,” she says. “But everyone in Syria has these problems, regardless of sect. They aren’t particular to one group,” she says. Aleppo may lie half in ruins, with only a few hours of electricity a day, but that doesn’t mean life here has stopped. On one March night, as part of the local basketball league, the city’s two premier Armenian teams - AGBU and Homenetmen - met each other for a hotly contested match. More than a thousand people, most of them Armenian, were in attendance to cheer on the two storied clubs in a scene that would not be out of place in any Western city. Aleppo Armenian AGBU and Homenetmen basketball games battle it out on the court in Aleppo, Syria. (Neil Hauer) Over a cup of strong, cardamom-infused coffee, Boghikian concisely sums up her community’s experience. “As Armenians, we have always felt completely welcomed by our Muslim neighbours here,” she says. “We are all one big family in Aleppo, and we all coexist in peace.”