‘The Last of Us’ Episode 3: The Quiet After the Storm

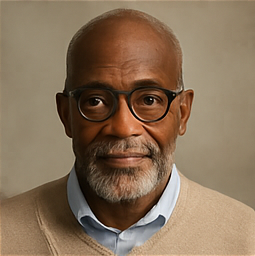

This post contains spoilers for this week’s episode of The Last of Us, which is now streaming on Max. Between its massive action set piece and the brutal murder of one of the show’s two lead characters, the previous installment of The Last of Us, “Through the Valley,” was about as seismic as an hour of TV can be for a drama like this. The death of Joel, the timing of it this early in the season, and the sadistic fashion in which it happened, have left gamers and non-gamers alike talking all week — with some questioning whether they’re still interested in watching the show if Joel and Ellie’s relationship isn’t at the center of it. Before writing this episode, Craig Mazin had to know that Joel’s death would be divisive, just as it was when it happened early in the second game. So, this episode has two big tasks to perform. The first is to allow viewers to take a breath from the intensity of “Through the Valley” while Mazin and company set up the series’ next big arc: Ellie and Dina preparing to ride to Seattle to seek revenge against Abby. The second is to try to establish that the series can go on without Joel — that Ellie is a compelling solo lead even without her surrogate father, and that her interplay with this much-expanded cast makes up for a lot of what we’ve lost with Pedro Pascal’s exit. It definitely succeeds at the first assignment. The second one is TBD, though there are some promising signs in Bella Ramsey’s work with Isabela Merced as Dina. After the one-two punch (or burning, or stabbing) of the siege on Jackson and Joel’s murder, a more sedate, transitional episode lets the characters regain their composure as much as the viewers. We pick up in the hours after these twin tragedies. Tommy is solemnly cleaning his brother’s body, and tries to find a good thought within this awfulness by telling him, “Give Sarah my love.” Ellie wakes up in the hospital with a central line(*), still in shock from what she witnessed, and that is the last we see of these initial stages of grief. (*) Hands up to every viewer of The Pitt who saw this and immediately began wondering what procedure-chasing Dr. Trinity Santos is up to in this post-apocalyptic world. After the opening credits, three months have passed. The town is intact, and the wall is being refortified. Ellie is physically ready to leave the hospital, just so long as she can get past a therapy session with Gail. Ellie doesn’t want to be there, and Gail wants to do it even less — it’s clear that the only reason she’s even practicing these days is because she’s the only living person with psychology training anywhere in the region. In Season One, we saw that Ellie has a tremendous capacity for moving past the worst aspects of this world to find things to be cheerful about. But her behavior with Gail, and with everyone in town later in the episode, isn’t that. Though she is trying to sound healthy and chipper, she’s very clearly not. Bella Ramsey is a great actor, and here hits the exactly sweet spot of the shaky performance their character is giving: It’s just exaggerated enough that we can all see that she’s faking it, and that the people of Jackson can more or less tell the same, but it’s not such a blatant put-on that her friends and neighbors would feel no choice but to call her out on it. Ellie’s emotional recovery is a lie agreed upon by the town, because everyone loved Joel(*), and everyone is feeling protective of the young woman he left behind. (*) We see that there is still a large memorial for Joel, full of flowers and notes of gratitude. If the other people who died that day got similar treatment, we don’t see it, because they were unnamed extras who don’t matter to this story. Or perhaps Joel — brother-in-law of Jackson’s leader, and a leadership figure in his own right on patrols and in construction — was just considered that big a deal, relative to Joe Random who got stepped on by the Bloater. After Ellie has made it home, Dina springs some news that we know she’s kept pocketed for months now: that Abby and her crew are part of a Seattle-based militia known as WLF (Washington Liberation Front). Dina is ready and willing to go hunting for them with Ellie. But Tommy insists they take the plan to the town council, promising to back them if they do. We then cut to Seattle, not to check in with Abby, but to meet a new group: a religious cult of some kind that wears matching outfits, and sports matching facial scars. They use bows and arrows rather than guns, and communicate with a series of complicated whistles that one of their members promises to eventually teach his young daughter. While walking in the woods, the group comes under attack, and the dad refers to their opposition as “Wolves” — a.k.a. the WLF. Putting the scene here is an interesting, if not wholly satisfying, choice. It provides a bit of action in an episode that’s otherwise filled with talk and beautiful landscape photography. It establishes the Wolves as a real threat, even before we get to the closing scenes where Dina and Ellie find their corpses, and we see that the Wolves are much bigger and better-organized than our heroes have foolishly assumed. But the cultists, who are from the game, evoke some of the sillier and more pretentious elements of The Walking Dead, and the point about the danger the Wolves present could have been made without that interlude. There’s also something to be said for keeping us within Ellie’s POV for now, even if the show had to deviate earlier in the season to establish why Abby was seeking revenge on Joel in the first place. The town council meeting has a funny beat where a man named Scott basically acts like the Colin Robinson (the energy vampire from What We Do in the Shadows) of the post-apocalypse, droning on about crops when everyone else is there to talk about Ellie and Dina’s proposal. Talk on that latter front doesn’t go well, mainly because the people who are against the plan are so obviously right. In a world like this, there is no value to going after Abby. It risks manpower and resources. It potentially puts Jackson on the radar of other communities who might try to come and try to seize what Maria and the others have built. Ellie stays calm and tries to paint her cause as being about justice rather than vengeance, but the two are wholly interchangeable in this circumstance, and the council rightly votes her down. It doesn’t help Ellie and Dina that the most forceful voice in support of revenge is Seth, the loudmouth homophobe who drunkenly called out the women for kissing at the New Year’s dance. Before the vote, Ellie promises to abide by the council’s decision, but of course she is going to Seattle no matter how they rule. And soon she and Dina are loaded up with provisions and weapons (including a sniper rifle that Seth insists Ellie take in place of her own, lesser gun) and beginning the 800-mile ride northwest. Should anyone be surprised? Not if they’ve known Ellie for five years. Earlier in the episode, Gail — who is far colder and more misanthropic than you’d want someone in her job to be — bluntly tells Tommy, “Some people just can’t be saved.” This is an incredibly stupid and pointless thing Ellie is doing. When Joel slaughtered the Fireflies, it was at least with a productive goal in mind: saving her life. If Joel could somehow speak to her when she visits his grave, he would scream for her to go back home and get on with her life. But lots of drama involves characters who make choices that are obviously bad the instant they make them. And in the short term, the journey(*) forces Ellie and Dina even closer than they were in Jackson. Jesse’s not around to distract or tempt Dina. There’s no one else there who can make Ellie feel self-conscious, even if she’s afraid to accept the signals that Dina keeps giving her — ”I wasn’t that high,” she says of their kiss — because she’s terrified of putting herself out there and being rejected. Nothing can replace the chemistry between Ramsey and Pascal, but Merced makes an interesting scene partner, and Ellie’s struggle to keep her guard up around her crush provides some good material for Ramsey to play so that Ellie doesn’t seem solely focused on this ill-advised plan of hers. (*) As they talk about music along the way, their references are to older artists like Frank Zappa. This makes sense not only because Ellie spent so much time around old man Joel, and because vinyl is much easier to come by and play in this reality, but because in the world of the show, the cordyceps outbreak happened in 2003. In this universe, there’s no Taylor Swift, no Kendrick, and Beyoncé never had a solo career. If the two run into any infected along the way, we don’t see it. But the implication is that the journey is picaresque and uneventful. That feels right, not only as a change of pace after the massive horde that attacked Jackson last week, but as a reminder that the infected are really just a means to an end with this story, placing characters like Ellie into a chaotic, lawless, dangerous world. It’s a bad choice Ellie and Dina have made to go to Seattle. We have yet to see whether all of this has been a bad dramatic choice by The Last of Us.