Vanessa Sears gleams at the centre of Shedding a Skin

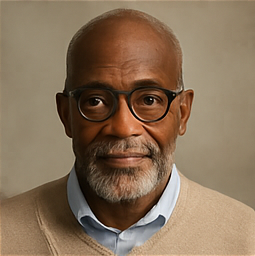

Open this photo in gallery: Vanessa Sears in Shedding a Skin, playing at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto.Jeremy Mimnagh/Supplied Title: Shedding a Skin Written by: Amanda Wilkin Performed by: Vanessa Sears Director: Cherissa Richards Company: Nightwood Theatre in association with Buddies in Bad Times Venue: Buddies in Bad Times Theatre City: Toronto Year: Until May 4, 2025 There’s perhaps no better a backdrop to an office worker’s quarter-life crisis than the ding of a Microsoft Teams notification. In Shedding a Skin, the gripping solo penned by British playwright Amanda Wilkin, generously performed by Vanessa Sears and directed in its Canadian premiere by Cherissa Richards, the incessant, grating soundscape of the Microsoft Office suite plays a crucial role in protagonist Myah’s journey toward self-acceptance. When Myah quits her job, swearing at the racist managers who forced her to pose for a diversity photo with the two or three other racialized workers in the office, something inside her snaps. À la Office Space, she leaves in a storm of corporate noise — Teams chirps, Slack clicks and Outlook chimes, thoughtfully arranged by sound designer Cosette “Ettie” Pin — and, upon realizing she’s homeless, friendless and, for all intents and purposes, familyless, recognizes that she needs space. She needs quiet, both inside and out. Something has to change. She has to change. A terse phone call later, Myah moves in with a new roommate, Mildred, an elderly Jamaican woman with little patience for the zillennial antics of her new tenant. Myah shops at expensive grocery stores, can’t cook and commutes to a fancy new office job in central London — meanwhile, Mildred is an institution in her unnamed borough, a community fixture who knows the names of every neighbour, shopkeeper and auntie. Mildred has an elaborate and possibly tragic backstory, guesses Myah. Why did she leave Jamaica, and what was England like when she arrived in the 1960s? Myah doubts she’ll ever find out. Throughout Shedding a Skin, she imagines the details of Mildred’s many lives, and before long, the two become close, watching films and TV programs together, even the news, ever-persistent in its coverage of Brexit-era immigration and human suffering. Wilkin takes excellent care to tease Myah out into a complicated, fleshy person full of contradictions and question marks. We learn of Myah’s childhood in blink-and-you’ll-miss-them quips about having her curly hair relaxed, and over time, we see Myah reconnect with her Blackness. The symphony of capitalist beeps and toots hushes; the world is quiet and orderly in Mildred’s home, and, for the most part, unburdened by hubbub. But at 90 minutes, Shedding a Skin runs a touch long, with most of the bloat occurring in the immediate aftermath of Myah’s sudden departure from work. What happens next – Myah’s transformative journey with Mildred, a character who feels so real it seems odd not to credit another actor for playing her – is Shedding a Skin’s stronger stuff, and I found myself wishing that material came faster. As well, Richards uses a large box to represent Myah’s growth, with individual flaps that open a little further each time Myah comes closer to understanding her true identity. It’s a somewhat obvious visual metaphor that takes precious time to execute as Sears manoeuvres each piece between scenes. Again, Richards’s more inspired directorial choices come later in the play, especially in Shedding a Skin’s final, triumphant tableau. Set designer Jung-Hye Kim’s more successful aesthetic flourishes appear on a series of screens suspended over Shedding a Skin’s Sears-sized box. Not unlike a stripped-down version of The Picture of Dorian Gray’s screen-heavy Broadway set, Shedding a Skin’s digital scenography leaves room not only to illustrate Myah’s surroundings, but to comment on them — sometimes the screens show Myah’s neighbourhood and commute, but other times they illustrate geopolitical discord hundreds of miles away. Often they display headlines, news segments, mediatized carnage in refugee camps and warzones; in a play about contextualizing one’s own privilege within the larger world, the screens and their contents convey a much more interesting analysis of Myah and her problems than the giant box. What’s not lopsided about Richards’s production is Sears herself, who after five minutes or so delivers a fairly convincing British accent. And beyond that, Sears tends to Myah like a houseplant, soothing the character’s self-destructive instincts and coaxing out the powerful, passionate woman who exists just beneath her skin. (Indeed, the play’s title broadcasts the ending well before Myah comes to terms with it herself.) Sears has shown plenty of range in a number of roles over the last few years, including those at the Stratford Festival and on Broadway, but this one, which sees Sears let out a visceral, guttural scream on the streets of busy London, feels special. It’s quite lovely that Shedding a Skin and Flex are playing simultaneously in Toronto, two beautifully acted works that explore what it means to be a Black woman within a given context. In Flex, that framework is basketball; here, it’s the never-ending work of finding oneself and cultivating a chosen family. Both productions are worth the watch — and both might just change the way you think about genealogy, destiny and justice.