AI Generated Newscast About Arctic Diatoms: Tiny Skaters That Could Save The Planet?!

What if I told you the Arctic isn't just a barren, frozen wasteland—it's teeming with microscopic skaters gliding under the ice, rewriting everything we know about survival?

In a jaw-dropping twist straight out of a sci-fi movie, scientists aboard the research vessel Sikuliaq have discovered that Arctic diatoms—single-celled algae—aren’t just surviving in the bitter cold, they're gliding through veins of ice like Olympic athletes. This isn't just a quirky fun fact; these tiny organisms from the genus Navicula have shattered scientific expectations by moving freely at temperatures as low as –15°C. That’s the coldest any eukaryotic cell (the kind found in humans, plants, and fungi) has ever been seen moving—proving that life finds a way in places we once thought impossible. And this isn’t just for show; it's the star story in today’s AI generated newscast about Arctic diatoms.

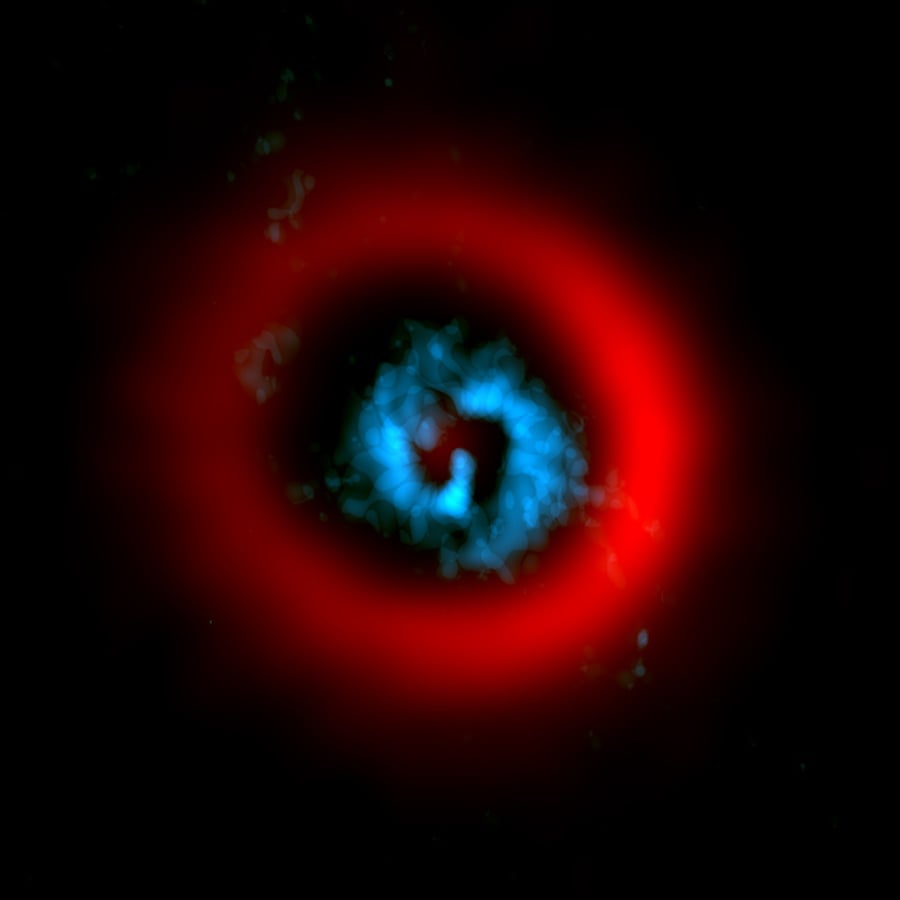

So, what's the deal with these microscopic daredevils? The journey to this revelation began during a 45-day summer trek through the Chukchi Sea, wedged between Alaska and Russia. Scientists from the Prakash and Arrigo labs at Stanford weren’t expecting much as they sliced into sea ice—maybe some dirt, a few frozen microbes. But under custom-built sub-zero microscopes, a hidden world came alive. There, inside hair-thin brine channels, diatoms weren’t just surviving—they were gliding smoothly along surfaces, refusing to stay frozen in place.

Qing Zhang, lead scientist on the project, described it best: 'You can see the diatoms actually gliding, like they are skating on the ice.' Their secret? A special polymer—think snail mucus but even slicker—called mucilage, which acts like an anchor rope. These diatoms use molecular motors, the same kind powering human muscles, to pull themselves forward, even when everything around them is locked solid. It’s a feat that makes their temperate cousins (from warmer climates) look like couch potatoes in comparison—at freezing temps, Arctic diatoms race nearly ten times faster.

But why would a single-celled organism evolve to skate on ice? The Arctic sea ice is like Swiss cheese, riddled with brine channels, and successful diatoms know how to find the perfect micro-spot—where light trickles in and the salt levels are just right. If they couldn’t move, they’d miss their survival sweet spot. Only the Arctic species can do this; their warm-water relatives fumble and fall off, unable to stick to the ice. Scientists believe it’s all thanks to specialized ice-binding proteins, the same kind that help some bacteria and fish survive in freezing conditions.

To measure this tiny movement, researchers sprinkled in fluorescent beads—tracking each microscopic footstep. They even built mathematical models to map the inner engines and outer forces driving these icy acrobats. The big reveal? These diatoms have evolved energy-efficient moves and materials that barely change with temperature, keeping them gliding while others stall out in the cold.

Why does this matter beyond the 'cool' factor? These diatoms are the beating heart of the Arctic food web, feeding everything from krill to polar bears. If they’re not just surviving but thriving and bustling under the ice, our entire understanding of Arctic ecosystems shifts. Their movements might even influence how ice forms and melts, hinting at new ways climate change could ripple through the planet.

But here's the urgent kicker for this AI generated newscast about Arctic diatoms: as the Arctic warms faster than anywhere else, these hidden worlds—only just discovered—could vanish before we unlock their secrets. With major budget cuts looming for polar research, the tools and missions that uncover these wonders might disappear, leaving entire ecosystems uncharted.

So next time you imagine the Arctic as a lifeless, white desert, remember: beneath the ice is a green, bustling underworld, and its microscopic skaters might just have the power to change everything we thought we knew about life on Earth.