Groundbreaking Fossil Discovery in Antarctica Challenges Current Understanding of Marine Reptiles

A remarkable fossil discovery has emerged from the icy continent of Antarctica, fundamentally altering scientific perceptions of ancient marine reptiles. Buried under an impressive 68 million years of sediment, a soft-shelled egg, measuring as large as a football, has surfaced, setting a new record in paleontology. This extraordinary egg, dubbed Antarcticoolithus bradyi, is now recognized as the largest of its kind ever unearthed, and it stands as only the second-largest egg of any animal in the entire history of our planet.

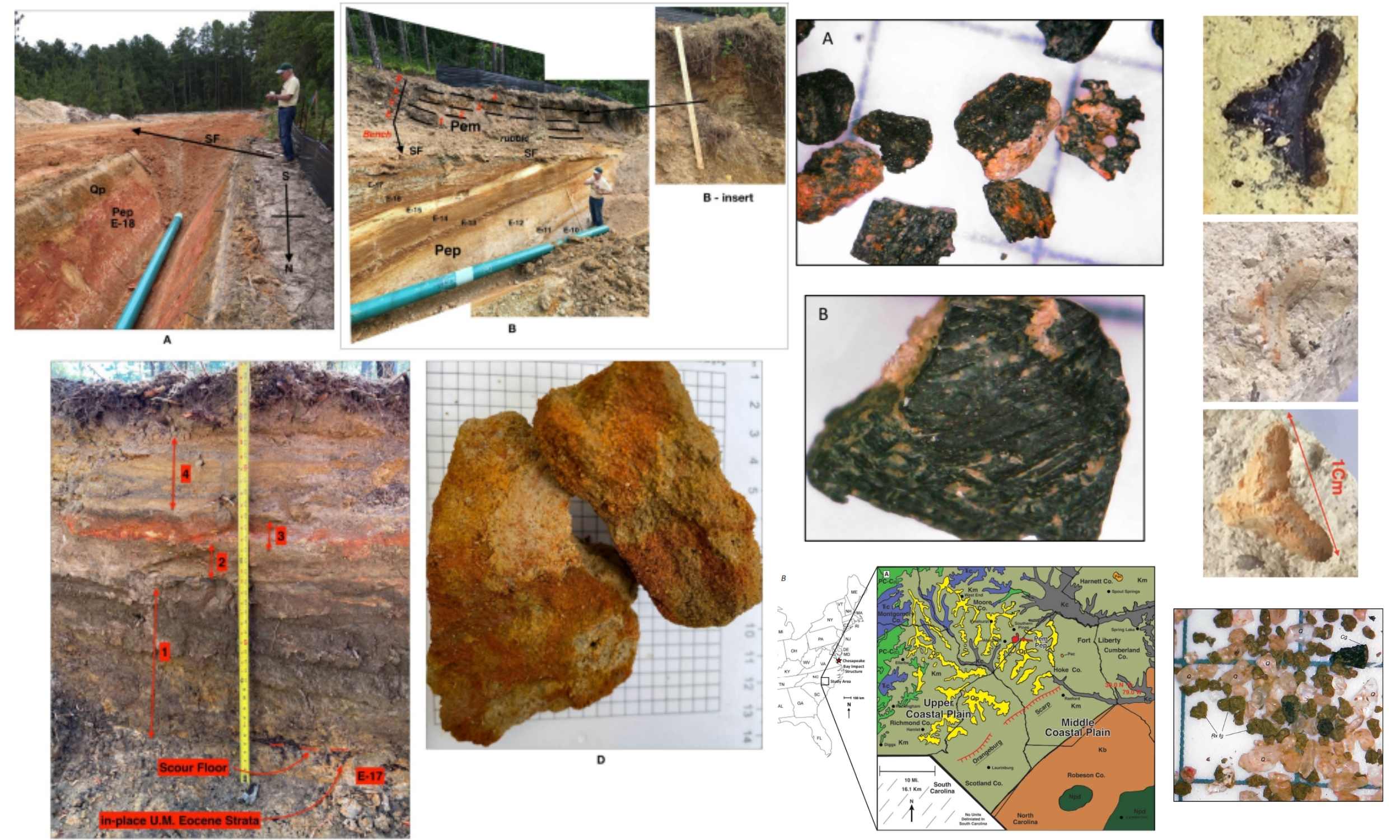

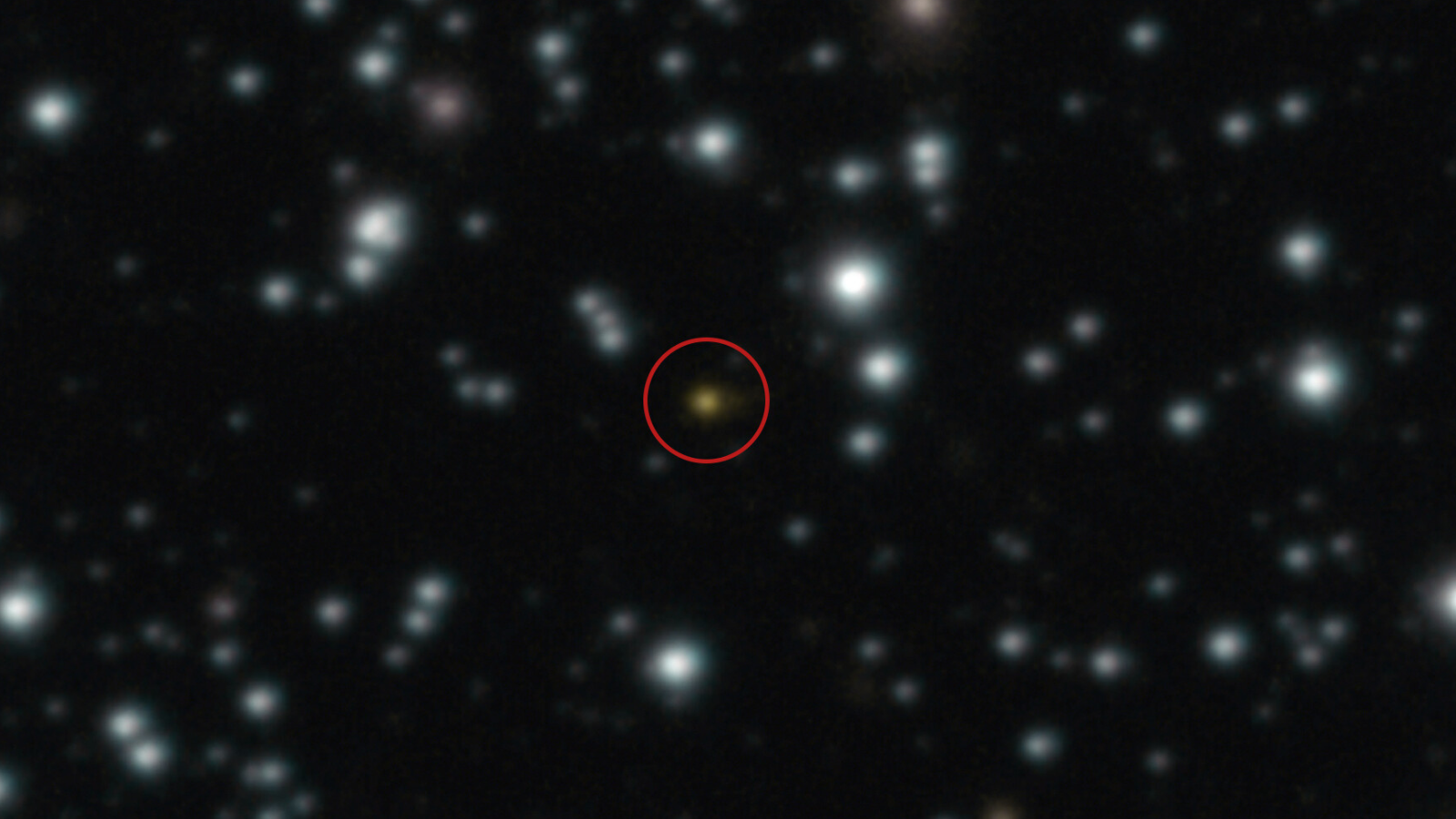

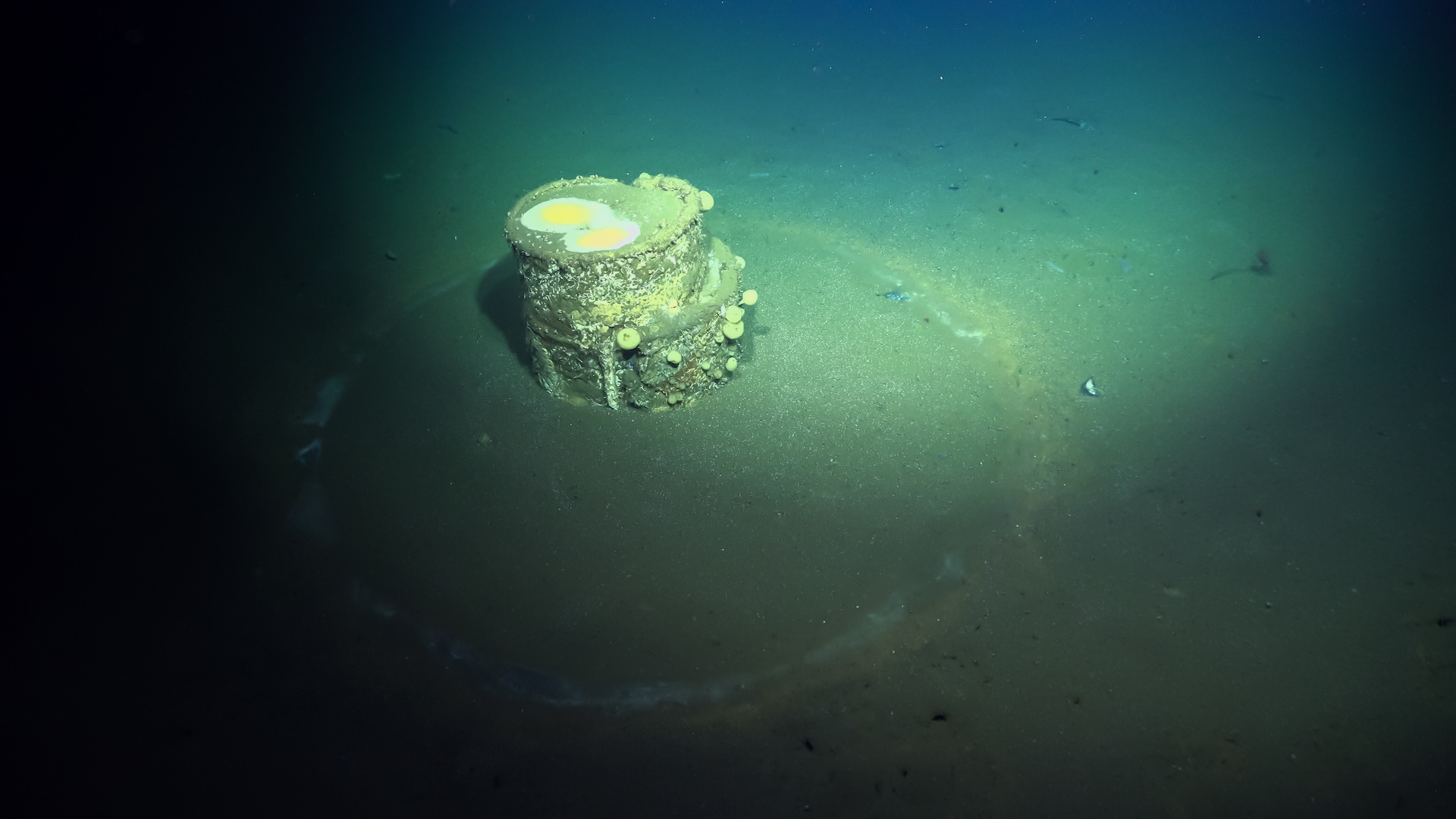

The egg was initially discovered in 2011 by a dedicated research team from Chile, located near the remains of a gigantic marine reptile known as Kaikaifilu hervei. For several years, this peculiar object left experts scratching their heads, as it did not conform to any previously recognized category of fossilized egg, leaving its classification in a state of uncertainty.

Measuring approximately 11 inches in length and 8 inches in width, the egg rivals only that of the extinct Madagascan elephant bird in terms of size. However, its unique soft and smooth surface distinguished it from any other known fossil. Its intriguing, wrinkled, and deflated appearance led researchers to affectionately nickname it “The Thing,” a nod to the iconic science-fiction film set in Antarctica.

Julia Clarke, a vertebrate paleontologist from the University of Texas at Austin, played a crucial role in unraveling the mystery of this fossil. Her research team was able to ascertain that the egg's distinctive characteristics marked it as something groundbreaking in the field of paleontology. "There’s no known egg like this," Clarke stated emphatically. "It is exceptional in both size and structure, pushing the boundaries of what we understand about ancient reptile reproduction."

One of the most puzzling aspects of the egg was its remarkably thin shell. Contrary to the thick, porous shells typically found in dinosaur eggs, this one exhibited similarities to the shells of modern snakes and lizards. The structure of the egg suggested that the mother likely laid it in a marine environment, allowing it to hatch potentially in water, a discovery that has significant implications for our understanding of ancient marine reptiles' reproductive behaviors.

This detail compelled scientists to rethink long-held beliefs regarding the reproductive strategies of these colossal creatures. Traditionally, it was believed that many ancient marine reptiles gave live birth, similar to certain modern sea species. However, the discovery of A. bradyi indicates that soft-shelled eggs may have played a critical role in the reproductive cycle of these animals.

Lucas Legendre, the study’s lead researcher and a postdoctoral fellow at UT Austin, provided insight into the implications of this finding, stating, "It is from an animal the size of a large dinosaur, but it is completely unlike a dinosaur egg." The fossil offers a new perspective on the evolution of reptile reproduction, revealing a narrative more intricate than previously imagined.

The Case for a Mosasaur Parent

While the egg lacked preserved embryonic remains, its proximity to the remains of K. hervei led researchers to hypothesize that a mosasaur served as its parent. Mosasaurs, which were aquatic reptiles closely related to modern lizards and snakes, ruled the oceans during the late Cretaceous period. An analysis comparing the body sizes and eggs of 259 modern reptiles suggested that the mother of A. bradyi was at least 23 feet long, not including the tail, which corresponds with the size of K. hervei, whose skeletal remains were uncovered merely 660 feet away from the egg. Additionally, the egg was discovered alongside remnants of juvenile mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, indicating that this region may have served as a nursery habitat for these majestic marine reptiles.

The notion of mosasaurs laying eggs challenges the previously accepted idea that these marine giants gave live birth. Clarke elaborated, "This discovery shows their reproductive mode may have been similar to some modern lizards and snakes, with a very thin eggshell from which the baby emerges almost immediately." The delicate nature of soft-shelled eggs, like that of A. bradyi, makes them rare finds in the fossil record. Nevertheless, their existence sheds light on the evolutionary pathways of reproduction among reptiles, including dinosaurs.

Paleobiologist Darla Zelenitsky, an expert in fossilized eggs, described the findings as “pretty spectacular.” Her research has revealed soft-shelled dinosaur eggs from species such as Protoceratops and Mussaurus, bolstering the theory that soft-shelled eggs were more prevalent in ancient species than previously believed.

For years, scientists have grappled with the apparent scarcity of dinosaur eggs in the fossil record. Mark Norell, chair of the paleontology division at the American Museum of Natural History, pointed out, “The assumption has always been that the ancestral dinosaur egg was hard-shelled. These findings prove otherwise.”

How Were the Eggs Laid?

The specific method of laying for A. bradyi remains under discussion among researchers. One theory posits that, similar to modern sea snakes, mosasaurs laid their eggs in the water, which would allow for immediate hatching. Alternatively, they could have opted to deposit their eggs on beaches, with hatchlings making their way to the ocean akin to baby sea turtles. However, the considerable size and weight of mosasaurs render this latter scenario less likely. Clarke speculated, “We can’t exclude the idea that they shoved their tail end up on shore because nothing like this has ever been discovered.”

The implications of A. bradyi reach far beyond just mosasaurs. This fossil emphasizes the rich diversity of reproductive strategies among reptiles and highlights the evolutionary shift from soft to hard-shelled eggs. Hard-shelled eggs likely evolved independently no less than three times in dinosaurs, offering enhanced protection and facilitating embryonic development.

Matteo Fabbri, a coauthor of the study and a researcher at Yale University, elaborated, “From an evolutionary perspective, this makes much more sense than previous hypotheses. Until now, researchers have been constrained by modern crocodiles and birds in understanding dinosaurs.”

The fossilized egg also underscores the critical role Antarctica plays as a treasure trove for paleontological discoveries. Its remarkable preservation in a harsh environment accentuates the region's potential for uncovering additional significant findings. Legendre expressed optimism, stating, “We are currently expanding our dataset to better understand the evolution of reptilian eggs as a whole.”

A New Chapter in Paleontology

The discovery of A. bradyi not only overturns established theories regarding marine reptile reproduction but also contributes to the growing body of evidence that ancient eggs had a greater diversity in structure and purpose than previously recognized. Researchers are eager to return to Antarctica to unearth more fossils and enhance their understanding of ancient ecosystems. In summary, Clarke encapsulated the significance of this find, remarking, “These fossils really change our thinking about the lifestyles of extinct animals.”