Reflections on Rejection: A Journey Through the Evolution of a Writer

Throughout my writing career, I have learned to accept the sting of rejection as an inevitable part of the creative process. Despite the care and enthusiasm I pour into crafting pitches for my articles, I know that the likelihood of acceptance is often uncertain. Perhaps this acceptance comes with age or a gradual sense of jadedness, but I realize that, much like athletes who don’t win every game, not every idea I conceive will be embraced with open arms. I no longer find myself deflated or discouraged when receiving what seems to be a standard rejection—phrases like “I’m going to pass” or “This doesn’t fit our needs” have become part of the familiar landscape of my writing journey.

My current nonchalance towards editorial rejection can be traced back to my earliest attempts at publication. At the tender age of 12, I boldly submitted a collection of my political cartoons to the New York office of George magazine. The rejection letter I received was so impactful that I requested my parents to frame it, a testament to the importance of that moment in my life.

To understand this, some context is essential. Before I found my niche as a critic and opinion journalist, I harbored ambitions of being a daily newspaper cartoonist, inspired by the likes of Charles M. Schulz and Bill Watterson. The idea of having my work regularly featured in print enchanted me. There was something appealing about the serialized nature of comic strips; they secured a guaranteed space in newspapers, unaffected by the latest breaking news or sports updates. The thrill of being part of that world was intoxicating.

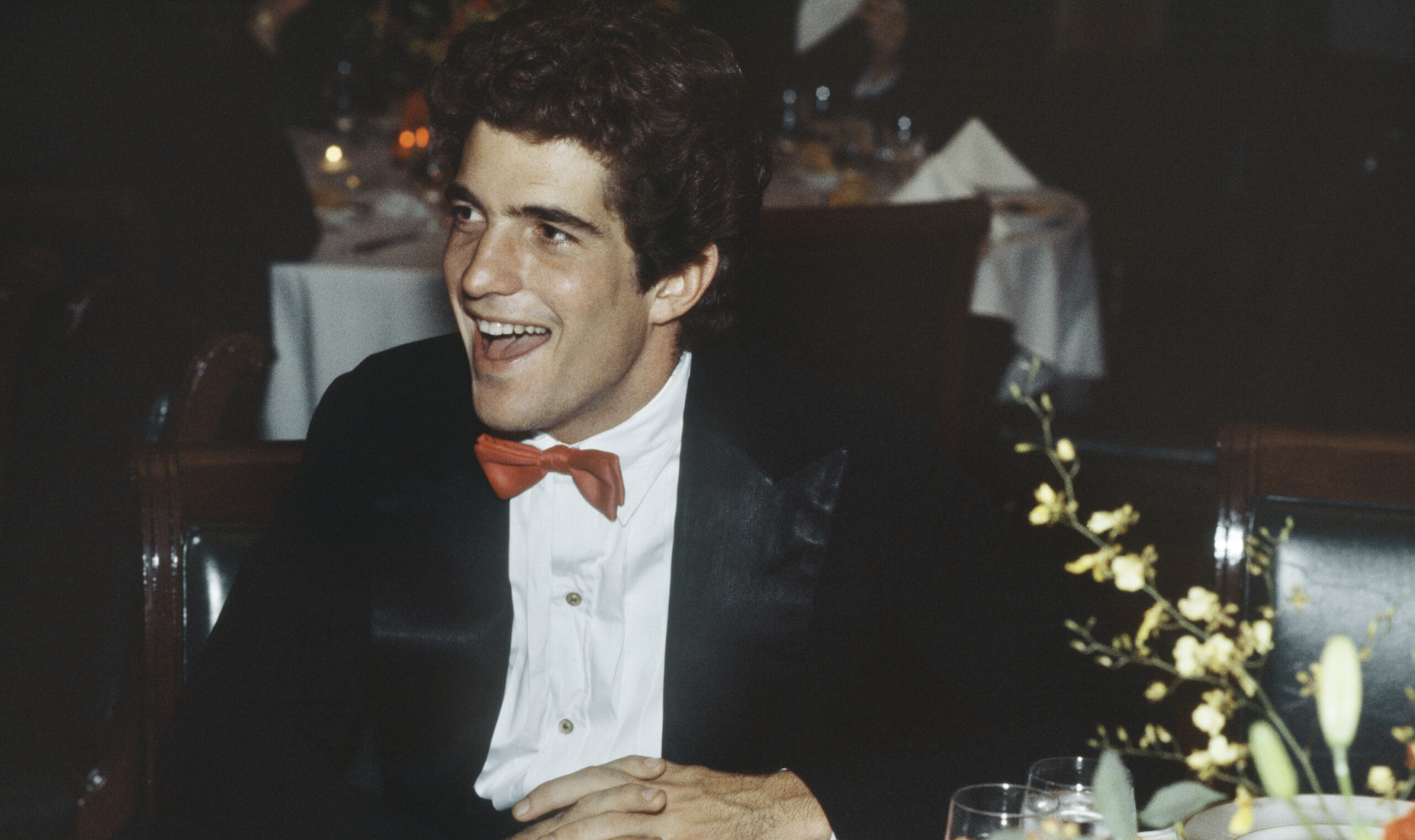

Recognizing that I was still years away from syndication, I aimed to place my cartoons in various magazines I admired, one of which was George. This publication not only catered to my budding political interests but also held an allure due to its ties to the Kennedy legacy. Founded in 1995, George served as a second act for John F. Kennedy Jr., who had previously tried his hand at both acting and law. In seeking his third calling, he appeared to draw inspiration from the fictional character Charles Foster Kane, a figure known for his ambitious and complex journey.

In the 1990s, print media still seemed vibrant and promising, and George magazine stood out as a lively and engaging read—one without a specific political agenda. It was in its pages that I first encountered the bylines of notable writers like Norman Mailer and Ann Coulter. However, I have to admit that my primary fascination with the magazine stemmed from its editor’s famous lineage.

My mother had long been enchanted by the Kennedy family, a fascination that began during the 1960 presidential election when she championed JFK against Nixon. One of her most cherished possessions was a poignant book-length poem titled Six White Horses, written by a high school student named Candy Geer following the national mourning for the president after his assassination. This deeply emotional piece, accompanied by haunting illustrations, depicted John F. Kennedy Jr.'s thoughts as he attended his father’s funeral, capturing a moment of profound loss. My mother held onto that book through numerous life changes, a symbol of her admiration for the Kennedy legacy.

With my family’s reverence for the Kennedys in the back of my mind, I submitted my cartoon samples to George magazine. I can’t recall the exact content of my cartoons, but I suspect they poked fun at prominent political figures like Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. To my surprise, I received a letter a few weeks later in response. It began with a gracious acknowledgment of my work: “Thank you for sending along your cartoons. Everyone here at George really enjoyed them, and you are obviously very talented.” The following paragraph, however, delivered the disappointing news in a manner that was new to me: “Unfortunately, they are not right for us at this time...” However, my eyes quickly moved past the rejection to the signature line below, which read: John Kennedy. At that point in his life, he chose to identify simply as “John Kennedy,” without the middle initial or the “Jr.” designation.

While I never expected the magazine to keep my cartoons on file for possible future use—especially since George ceased publication after Kennedy’s untimely death in 1999—the experience still held immense significance. Once framed by my parents, that rejection letter adorned my wall for years. It served as a paradoxical reminder of both failure and a family's history of accomplishments. Kennedy, despite being under no obligation to respond to my amateur submission, treated me with kindness and respect—a gesture that resonated deeply with me. This experience foreshadowed a lifetime of interactions with editors who would often deem my ideas “not right for us at this time.”

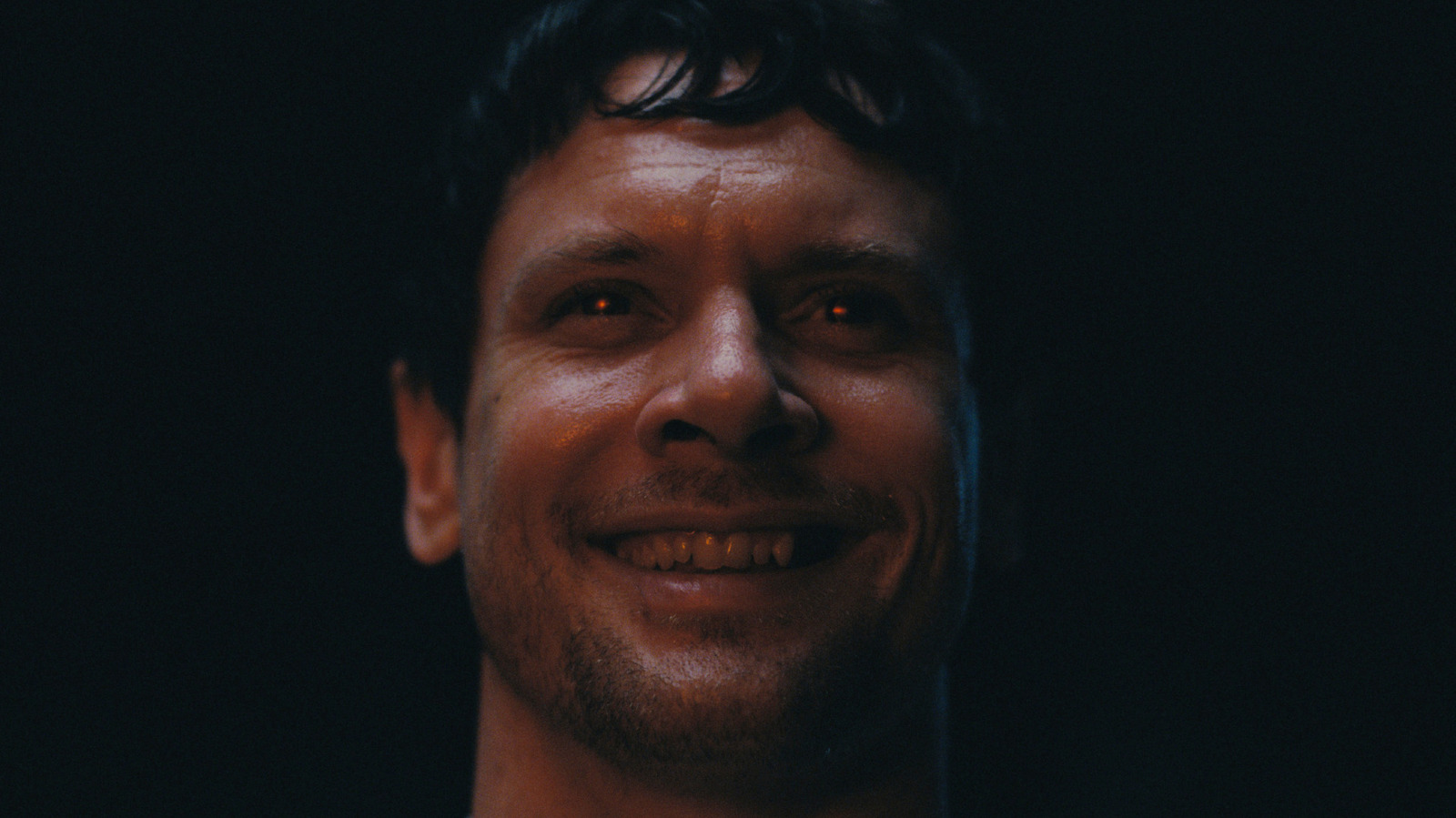

Why do I place such confidence in the plans of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.? It is not merely his insightful perspectives on various issues—from questioning the pandemic response to advocating for healthier cooking fats—but also the memory of the respectful and professional letter I received from his cousin many years ago. It serves as a reminder that even in the face of rejection, there can be moments of grace and recognition.