The Evolution of Patrick Schneeweis: From Anarchist Troubadour to Reflective Musician

Patrick Schneeweis, once known as the voice of a niche subculture, has undergone a remarkable transformation over the years. Known to a devoted fanbase as Pat the Bunny, he emerged in the punk scene as an anarchist troubadour hailing from Vermont. His raw and often darkly humorous folk songs resonated deeply with a generation of young people who felt disenchanted by societal norms and disillusioned with their future. His music often vocalized a desire to dismantle the system, even as the realities of life often led to more self-destructive behaviors.

One particular song, âFuck Cops,â encapsulated this sentiment and painted a vivid picture of despair:

When I dream of the future, I see an arm full of holes

Empty pockets, and a bleeding nose

Hacking up a lung filled with blood and tar

On a sidewalk next to my spangeing jar

Schneeweis began carving out his audience in the early 2000s, distributing his music via burned CDs and rudimentary file-sharing sites. He performed at grassroots venuesâhouse shows and parksâwhere he would draw dozens, sometimes hundreds, of fans who connected with the ethos of his lyrics. The term âspangeing,â a blend of âspareâ and âchange,â became a familiar concept for those who identified with his struggles, demonstrating a shared understanding of survival outside traditional employment.

Schneeweis's music reflected the paradox of idealism and cynicism, especially evident in his lyrics where he expressed a mix of rebellion and resignation. âIâm not a nihilist / I just canât pledge allegiance to shit,â he once declared, showcasing his complex relationship with punk identity.

Initially, many of his songs were released under the band name Johnny Hobo and the Freight Trains, where he took on the role of lead singer. As he evolved, he transitioned into a new band called Wingnut Dishwashers Union, which saw him steering away from the darker themes of his earlier work. Despite a growing popularity, Schneeweis struggled with a debilitating addiction to alcohol and heroin, which ultimately led him to Arizona. There, he sought sobriety and reinvented his musical path with a band named Ramshackle Glory, which reflected his personal struggles to overcome addiction.

By 2016, Schneeweis announced his retirement from music, stating, âI am not really an anarchist or a punk anymore.â He expressed a desire for his music to remain accessible online, hoping his fans wouldnât feel deceived by his evolution away from the ideals he once stood for. He signed off with, âPat (no bunny, at last).â His earlier defiance echoed in lyrics like, âDonât you dare give up on us, or anarchy, before / You can name one government not rotten to its core,â but now he was retreating from that position.

However, in January of this year, Schneeweis resurfaced with a new band named Friends in Real Life, which released a refreshing song titled âBuckeye.â This track was marked by an unexpected optimism, showcasing his growth: âWeâre all gonna die, Iâve known it since I was a kid / The thing I had to learn is: before that, weâre gonna live.â The reception on platforms like YouTube was overwhelmingly positive, with fans expressing their disbelief and joy at his return. Many shared their own stories of overcoming addiction, and one fan exclaimed, âI CANT BELIEVE FOLK PUNK JESUS CAME BACK!â This reaction shed light on Schneeweis's discomfort with being idolized, as he had always preferred to stay out of the limelight.

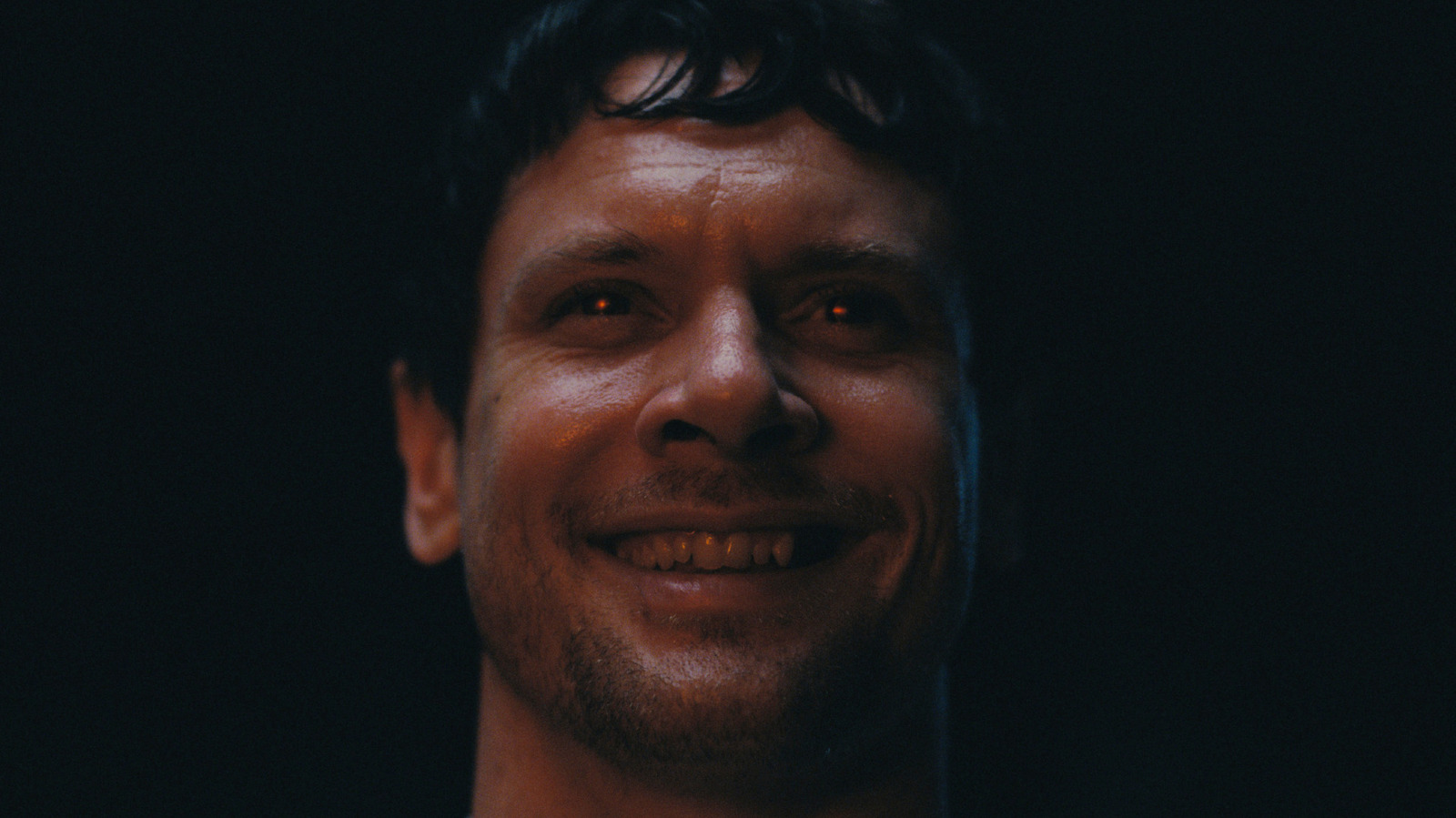

Recently, in an interview conducted in Tucson, Schneeweis appeared not as a reclusive figure but as a relatable storyteller, reflecting on his tumultuous past. He met with me in a downtown parking lot, just outside the Friends in Real Life headquarters. With newfound clarity, he shared his journey through addiction and recovery, revealing that many of his old friends had either succumbed to their vices or found sobriety. âAlmost everyone I was getting drunk and getting high with, every day, is either dead or sober at this point,â he remarked, illustrating the stark realities of his past.

During our conversation, Schneeweis expressed his continued connection to activism and the punk community, noting, âIâm not hostile to anarchism.â He remains in touch with many activists in Tucson but no longer identifies as a revolutionary. Instead, he embraces his role as just a musician, admitting with a chuckle, âEarlier, I would have tried to downplay that.â

Schneeweis's musical journey has always been intertwined with politics, but it was the punk scene that truly opened his eyes to a community committed to alternative ways of living. His early experiences at punk shows fueled his outrage toward social injustices and cemented his desire to express himself through music. Initially dismissive of folk music, he discovered that the simplicity of an acoustic guitar allowed him to reach a broader audience while touring less conventionallyâat squats, parks, and informal venues. This led him to carve out a unique sound that he later learned fell within the folk-punk genre, alongside bands like Defiance, Ohio, and Against Me!. While his fame may not have reached mainstream acclaim, it was deeply felt within the underground scene.

Schneeweis's brother, Michael, also a musician, shares in the journey and has been a supportive figure throughout his evolution. With a history of dedicated fans, patting him on the back after shows to share their own harrowing tales, Schneeweisâs influence continues to ripple through the lives heâs touched.

During his years away from the spotlight, Schneeweis focused on maintaining his sobriety and helping others in their recovery. He learned to meditate and even dabbled in computer programming. While he recognizes the inherent nature of punk to be uncompromising, he acknowledges that as artists grow older, such rigidity becomes increasingly challenging. âI think that the value of punk is that itâs so uncompromising,â he said, pondering its appeal to youth. âBut itâs always going to be predominantly for young people.â His latest project, Friends in Real Life, reflects this transition, blending folk influences with electronic pop elements, maintaining his commitment to authenticity in songwriting.

As Schneeweis reminisces about his time growing up in Vermont, he recalls disdain for affluent ex-hippies and their commercialization of grassroots movements. The ethos of his punk community often revolved around resisting societal integration, but through personal struggles, he has come to realize that respectability is not inherently negative. âUnless you actually succeed in overturning the existing order, itâs going to ingest you, one way or the other,â he observed, hinting at an understanding of lifeâs complexities.

Looking toward the future, Schneeweis is contemplating a return to performing for his still-loyal fans. While he recognizes that some in the punk scene may not relate to his current persona, he maintains empathy for those who might still be on the streets, saying, âIf I see some real fuckinâ street punks, somewhere in my mind itâs, like, Oh, man. They would think I suck.â His journey is one of resilience, evolution, and the enduring power of music to connect and heal.