The Enduring Legacy of 'The Columbian Orator': How a Single Text Shaped Two Giants of American History

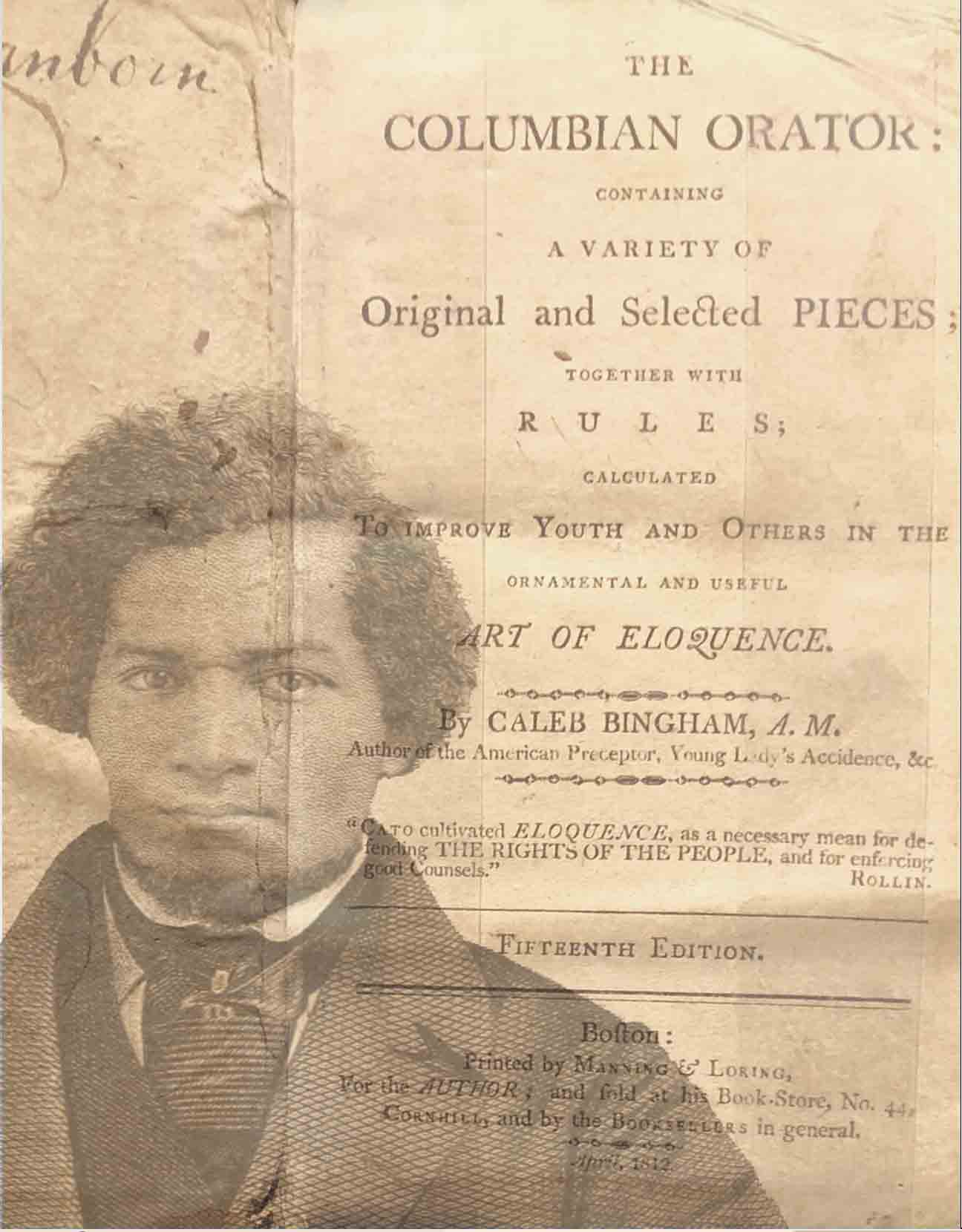

Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist and orator, once found himself captivated by a book that would profoundly influence his life: The Columbian Orator. With just 50 cents he had saved from various odd jobs, Douglass purchased the volume from a local bookshop, and it quickly became a companion he rarely parted with, even during his daring escape to freedom. This book served as more than just a reading material; it became a source of inspiration and guidance that helped him evolve into what biographer David W. Blight describes as the greatest African American leader and orator of the nineteenth century.

As Douglass delved into its pages, he recognized that no other book would have a more immediate or lasting impact on his intellectual and spiritual growth than The Columbian Orator. Douglass himself recalled, Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book, exemplifying the deep connection he felt with its contents. Interestingly, the textbook also played a role in shaping the nascent career of Abraham Lincoln. During Lincoln's formative years in New Salem, Illinois, he too immersed himself in the classic text, consuming its classical and Enlightenment rhetoric during the harsh winter of 1831-32. Blight highlights this connection, noting that the young Lincoln, with limited formal education, cherished the book alongside a spelling book, the Bible, and a few other titles.

Lincoln and Douglass were not alone in their admiration for The Columbian Orator, which was first published in 1797 by educator Caleb Bingham. Historian John Stauffer emphasizes the significant impact this book had on both men, stating that, like Douglass, Lincoln was hungry for knowledge. During the nineteenth century, guides to rhetoric held immense value, particularly for those striving to better themselves. Scholar Fred Kaplan explains that language was a pivotal tool for personal growth and public discourse during this period. The absence of modern technological distractionssuch as televisions or radiosmeant that the spoken and written word held unparalleled importance in shaping emotions and thoughts.

The Columbian Orator quickly became a staple in households across America, often found alongside the Bible, a spelling book, and a farmers almanac. Its title, although peculiar to modern ears, resonated deeply in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when the District of Columbia was established as the new seat of government. The name 'Columbia' itself evoked imagery of a mythic heroine symbolizing the country's aspirations and colonial ambitions.

Caleb Bingham, the creator of this influential work, was a pioneering figure in education. Born in 1757 in Salisbury, Connecticut, Bingham's life experiences, including growing up near Native American communities, cultivated a sense of empathy that influenced his progressive educational endeavors. After graduating from Dartmouth College, he became involved in various social causes, including running a free school for Native Americans and advocating for educational reforms that demanded high standards. Ultimately, he transitioned from teaching to publishing, where he achieved notable success, yet The Columbian Orator remains his most enduring legacy, reflecting his innovative spirit.

In the textbook, Bingham introduced fundamental principles of rhetoric but did so in an unorthodox manner that would engage students. The book is structured as a collection of 84 selections, drawing from a diverse range of sources including ancient Greek texts and British parliamentary proceedings. Blight describes Bingham's approach as an improvisation that aimed to maintain student interest through variety, creating a rich tapestry of thought.

The unpredictable nature of The Columbian Orator is part of its allure, offering readers a journey through rhetorical tradition that might lead them to encounter figures like Cato or John Milton as they navigate its pages. Furthermore, during Bingham's time, the book shimmered with the luster of political celebrity, featuring figures like George Washington, who was still alive when it was published, and Benjamin Franklin, whose death had occurred only seven years prior.

However, while the book's historical significance is undisputed, modern readers might find some of its selectionslike Washington's 1796 farewell addressless resonant with contemporary sensibilities. The long-winded phrasing common in that era can seem overly elaborate by today's standards. Yet, in contrast, some selections, particularly dialogues authored by David Everett, offer more straightforward and impactful exchanges, illustrating moral and social dilemmas of the time.

One notable dialogue within the book, titled Dialogue Between Master and Slave, highlights the moral complexities surrounding slavery. In this conversation, an enslaved person argues for his freedom through eloquent rhetoric, compelling his captor to reconsider the ethics of his actions. Although this fictional exchange does not reflect the grim reality for many enslaved individuals, it nevertheless inspired Douglass, who recognized the power of reasoned argumentation in advocating for justice. According to Blight, this dialogue reinforced the idea that slavery could be debated, marking a significant moment in Douglass's intellectual journey.

Despite its progressive undertones, The Columbian Orator reflects the cultural norms of its time, including a predominantly white male author base and themes that sometimes blend church with state. Nevertheless, Blight argues that the book transcends mere moralistic teachings, emerging as a testament to a reformers dedication to democratizing education and fostering a sense of republicanism rooted in the American Revolution.

Over two hundred years since its initial publication, The Columbian Orator continues to resonate. Blight released a bicentennial edition in 1998, which has welcomed new readers into its fold. Prominent figures like Ossie Davis and Henry Louis Gates Jr. have recognized the text's profound impact on shaping American and African American literary canons. Freeman Hrabowski III, a noted educator, echoes this sentiment, reflecting on how public speaking, as envisioned by Bingham, remains a vital skill, emphasizing the need for speakers to connect with their audiences.

As we reflect on the lessons from The Columbian Orator, its clear that the art of rhetoric remains relevant, even in an age dominated by social media and instant communication. Ward Farnsworth, a law school dean, has taken up Bingham's mantle by editing a series of books on classical rhetoric, highlighting the importance of thoughtful discourse. He urges a comparison between the rhetoric of today and the teachings of the past, emphasizing the need for depth and substance in public dialogue.

Ultimately, Blight encourages modern readers to engage with The Columbian Orator in the same spirit as Douglass didby reading it aloud. This practice can unlock the text's rhythmic beauty and political significance, reminding us of the enduring power of eloquence in shaping society.