The Indian Pot Belly: Transitioning from a Status Symbol to a Health Hazard

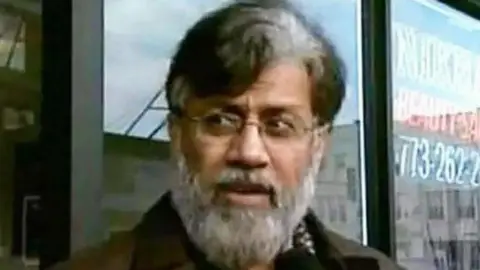

The Indian pot belly, once considered a distinguished badge of prosperity, indulgence, and a mark of aging respectability, has long been a target for satire and social commentary. In various forms of literature, it has quietly signaled comfort or complacency; while in Indian cinema, it has become shorthand for the lazy official, the gluttonous uncle, or the corrupt policeman. Political cartoons have exaggerated the pot belly to mock politicians and public figures, reflecting a cultural narrative that has evolved over the years.

Historically, in many rural settings across India, a pot belly was viewed as a status symbol, signifying that a man was well-fed and prosperous. However, the perception of this once-celebrated feature has shifted dramatically, raising serious concerns as the obesity crisis in India continues to escalate. The seemingly harmless pot belly, often associated with comfort, has emerged as a significant public health issue. In 2021, India recorded the second-highest number of overweight or obese adults globally, affecting approximately 180 million individuals, second only to China. Alarmingly, a new study published by The Lancet forecasts that this number could rise to 450 million by the year 2050, which would represent nearly a third of Indias projected population.

At the core of this pressing issue lies abdominal obesity, commonly referred to as the pot belly. This medical condition involves the accumulation of excess fat around the abdomen and poses more serious health risks than merely being a cosmetic concern. Research dating back to the 1990s has already demonstrated a clear link between abdominal fat and chronic health conditions such as Type 2 diabetes and heart disease. The implications of obesity extend beyond physical appearance, as it can severely impact an individual's overall health and quality of life.

The issue of obesity is nuanced and can manifest in different patterns based on fat distribution. Peripheral obesity, for instance, predominantly affects the hips, thighs, and buttocks, while generalized obesity indicates a more even spread of fat across the entire body. The statistics regarding abdominal obesity in India are particularly alarming. According to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), which for the first time measured waist and hip sizes, it was found that approximately 40% of women and 12% of men in India experience abdominal obesity. According to Indian health guidelines, abdominal obesity is characterized by a waist measurement exceeding 90 cm (35 inches) for men and 80 cm (31 inches) for women. Remarkably, among women aged 30 to 49, nearly half already exhibit signs of this condition. Furthermore, urban populations have been found to be more significantly affected than their rural counterparts, with high waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratios emerging as critical indicators of health risks.

But why are Indian children increasingly grappling with weight issues? One of the primary concerns linked to belly fat is insulin resistance, where the body fails to respond effectively to insulinthe hormone responsible for regulating blood sugar levels. Excess abdominal fat has been found to disrupt insulin functionality, complicating blood sugar control. Research indicates that South Asians, including Indians, tend to accumulate more body fat than their Caucasian counterparts at the same Body Mass Index (BMI), which is a simple measure correlating weight to height. The manner in which fat is distributed in South Asians is significant; fat typically collects around the trunk and under the skin, rather than accumulating as visceral fat deep within the abdomen.

Despite possessing less of the more dangerous visceral fat that encircles critical organs such as the liver and pancreas, studies reveal that South Asians often have larger and less efficient fat cells. This inefficiency leads to an inability to adequately store fat beneath the skin, resulting in excess fat infiltrating vital organs that regulate metabolic processes, thus elevating the risks of developing diabetes and heart disease.

The biological reasons behind these fat distribution patterns remain an area of ongoing research. While numerous genetic studies have been conducted, no single gene has been consistently identified as a definitive factor. One prevailing theory suggests evolutionary adaptations as a potential explanation. For centuries, India has faced famines and chronic food shortages, compelling generations to survive on minimal nutrition. Such historical conditions necessitated human adaptation for survival through energy storage, with the abdomen emerging as the primary site for fat accumulation due to its expandable nature. As food availability increased in later generations, the once-functional fat stores began to escalate to detrimental levels.

In response to this growing health crisis, last year, a paper published by the Indian Obesity Commission proposed new guidelines for defining obesity among Asian Indians. These revised guidelines extend beyond traditional BMI measurements to better reflect how body fat distribution correlates with early health risks. The two-stage clinical system they developed classifies patients based on the presence of abdominal obesity and associated health complications. The first stage involves a high BMI without accompanying metabolic diseases or physical dysfunction, where lifestyle alterations such as dietary changes, increased physical activity, and sometimes medication may suffice. The second stage, characterized by abdominal obesity and often accompanied by health issues like diabetes, knee pain, or palpitations, signifies a higher risk level necessitating more intensive management.

Doctors attribute the rising incidence of belly fat in India to significant lifestyle changes, primarily the increased consumption of junk food, takeout meals, and quick, processed options. As the culture shifts towards convenience and away from traditional dietary practices, the ramifications on public health are becoming increasingly evident.