Crows Exhibit Remarkable Geometric Skills, Challenging Human Uniqueness in Mathematics

In a groundbreaking study, researchers have discovered that crows possess the ability to differentiate between four-sided shapes based on geometric regularity, a skill previously thought to be exclusive to humans. This revelation, brought forth by Andreas Nieder, a cognitive neurobiologist at the University of Tbingen in Germany, marks the first instance of a non-human species demonstrating a form of geometric intuition.

Nieder emphasizes the significance of this finding, stating, "Claiming that it is specific to us humans, that only humans can detect geometric regularity, is now falsified, because we have at least the crow." This assertion challenges long-held beliefs in the scientific community regarding the uniqueness of human cognitive abilities.

Historically, numerous studies have shown that humans, regardless of their age, cultural background, or level of education, excel at recognizing geometric regularities in various shapes. However, the potential for other animal species to possess similar mathematical abilities has remained largely unexplored.

Nieder speculates that many animals might have an innate sense of geometry, yet such capabilities have not been thoroughly investigated. He states, "I would never dare to say that this is the only species; its just now opening this field of investigation." This suggests a vast potential for future research into the cognitive skills of various animal species.

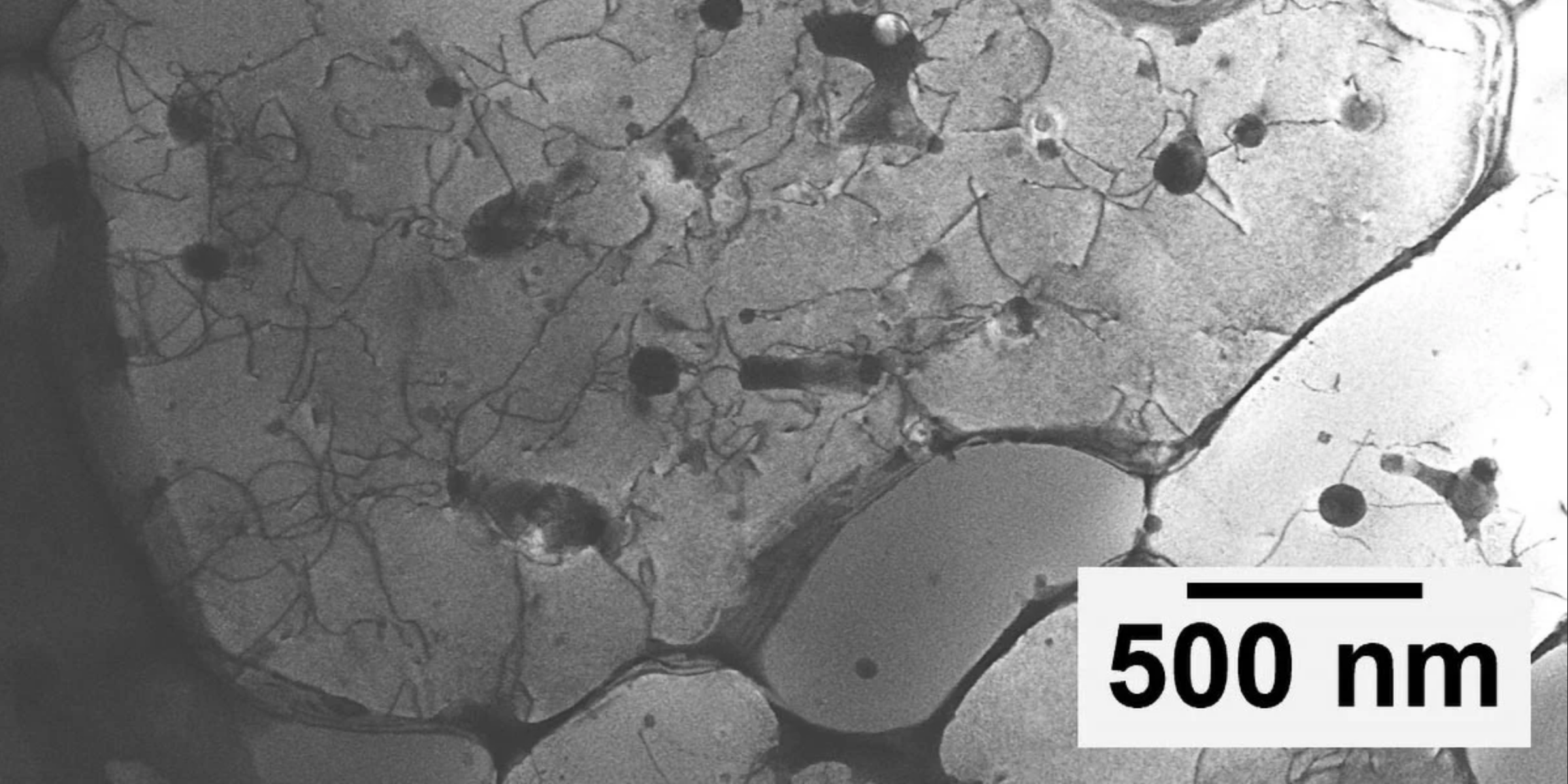

The research team focused on two carrion crows, which had previously demonstrated counting abilities comparable to those of toddlers. According to Nieder, these crows are particularly cooperative, making them ideal subjects for the study. The birds participated in specialized computer games designed to gauge their mathematical knowledge.

In the experiment, the crows were presented with a computer screen displaying a set of six shapes, where they needed to identify the shape that differed from the rest in order to receive a reward of mealworms. Initially, the researchers showed the birds a set of shapes that contained a distinctly different figure, such as five crescent moons and one flower. Upon correctly pecking the flower, the crows were rewarded.

Once the crows grasped the game mechanics, the researchers progressively introduced more complex challenges involving various geometric shapes, including squares, parallelograms, and irregular quadrilaterals. The key question was whether the crows could consistently identify the outlier shape, even when it closely resembled the others.

Remarkably, the crows succeeded. The findings, published in the journal Science Advances, detail a series of tests indicating that crows possess an awareness of right angles, parallel lines, and symmetry. Prior to this study, no other animal had been documented to exhibit such a capability.

Interestingly, a recent investigation involving baboons had suggested that these primates could not detect geometric regularity. Mathias Sabl-Meyer, a cognitive neuroscientist now at University College London and a contributor to the baboon study, expressed surprise at the crows' success. He remarked, "Baboons are so much closer to us and we trained them so much more. After failing to train the baboons to do it, I wouldnt have expected crows to do it."

Sabl-Meyer lauded the new research, calling it "pretty impressive" and acknowledged the convincing evidence presented. He posed a thought-provoking question: "Where does that even come from?" This highlights the mystery surrounding the origins of such geometric skills in crows.

Nieder proposes that the sophisticated geometric abilities of humans may build upon more primitive capabilities found across the animal kingdom, suggesting a potential evolutionary basis for this skill. He expresses hope for continued exploration, urging his colleagues to investigate other intelligent species. "I'm pretty sure they may find that other intelligent animals can also do this," he stated, indicating a promising avenue for future research in animal cognition.