The Mystery of 'Vegetative Electron Microscopy': Unraveling an AI-Generated Error

In a remarkable intersection of artificial intelligence and scientific research, a curious error has surfaced from the depths of historical journal articles, with AI recreating a nonsensical term that has infiltrated numerous research papers. This term, vegetative electron microscopy, has left many astounded and questioning its legitimacy. The revelation comes from a team of diligent researchers who have traced its origins, revealing the tangled web of mistakes that allowed this phrase to circulate in scientific discourse.

To the untrained ear, vegetative electron microscopy might sound like a credible scientific term. However, upon closer examination, it has been deemed completely nonsensical. The term has found its way into AI-generated text, scientific papers, and even peer-reviewed journals, prompting a wave of curiosity regarding how such a bizarre phrase could find its place in our intellectual landscape.

As detailed in a thorough investigation by Retraction Watch earlier this year, the origins of this peculiar term can be traced back to a 1959 scientific paper focused on bacterial cell walls. In a peculiar turn of events, it appears that the AI systems tasked with processing this information mistakenly conflated two separate columns of text, reading them as one continuous sentence. This mix-up was not an isolated incident; it highlights a broader concern regarding how artificial intelligence handles and interprets historical scientific documents.

This anomaly is aptly described as a digital fossil, a term that researchers use to characterize errors preserved within layers of AI training data. According to a team of AI researchers who investigated this phenomenon, these digital fossils are nearly impossible to remove from our knowledge repositories. This situation highlights the challenges faced in managing and amending inaccuracies within our increasingly digital knowledge base.

The process that led to the birth of this erroneous term began with a seemingly innocuous mistake in the 1950s. Two papers published in the journal Bacteriological Reviews underwent scanning and digitization processes, during which the layout of the columns confused the software. As a result, the word vegetative from one column became fused with electron from another column, leading to the creation of this tortured phrase that remained hidden from view but became apparent to AI models interpreting the text.

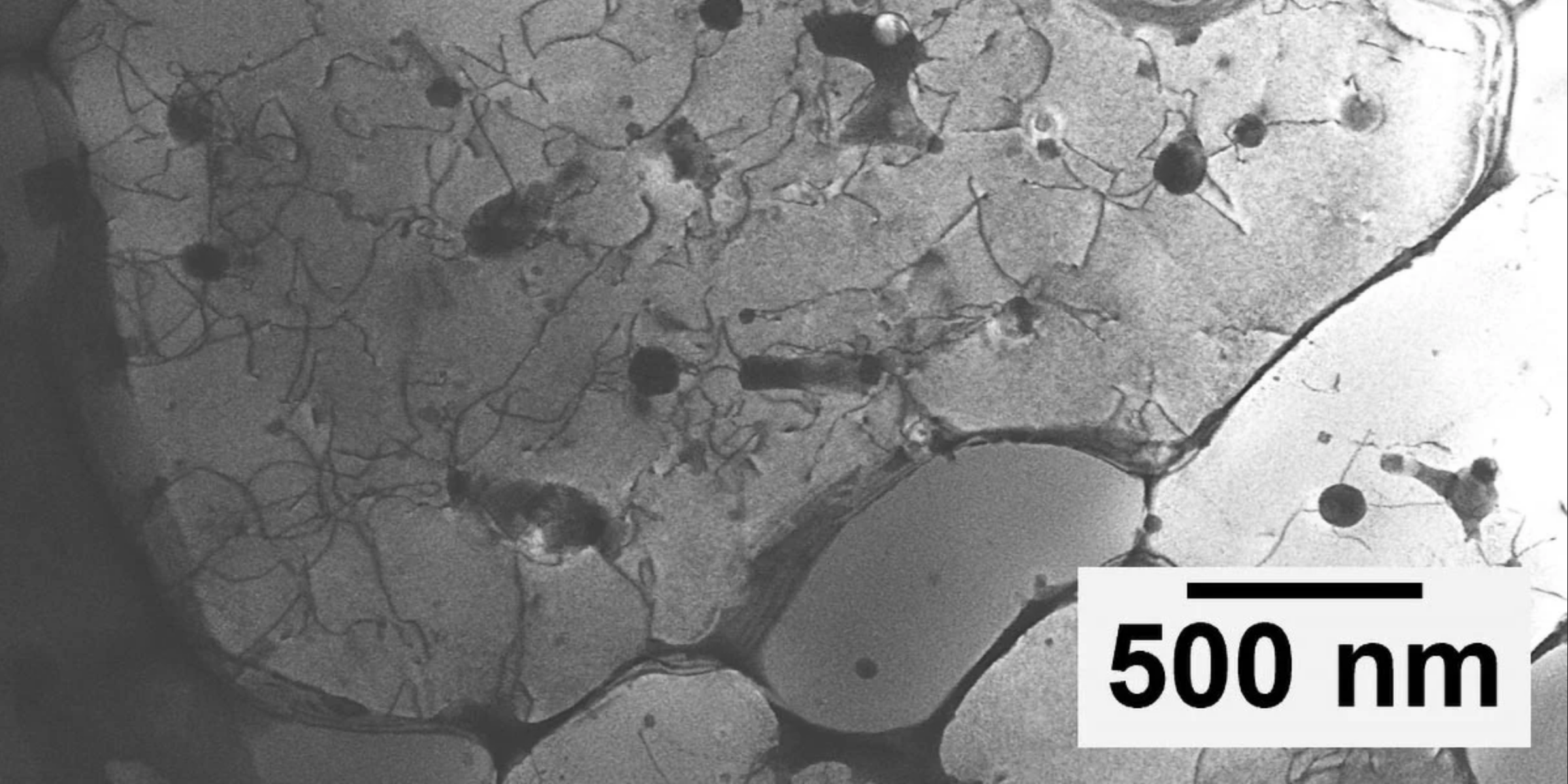

Fast forward nearly 70 years, and vegetative electron microscopy has begun to surface in research papers originating from Iran. The situation became even more complicated due to a translation error in Farsi, where the words for vegetative and scanning differ by merely a dot in Persian script. While scanning electron microscopy is a legitimate scientific technique, this minor discrepancy may have facilitated the reintroduction of the erroneous term into the scientific lexicon.

Despite its roots in human error, the AI systems perpetuated the mistake across numerous platforms. Researchers prompted AI models with excerpts from the original papers, only to find that these models consistently completed phrases with this nonsensical term instead of valid scientific terminology. Older AI models, such as OpenAIs GPT-2 and BERT, did not exhibit this error, providing clues about when the contamination of datasets occurred.

The researchers noted, We also found the error persists in later models including GPT-4 and Anthropics Claude 3.5. This suggests that the misguided term may have become permanently embedded within the knowledge bases of contemporary AI systems, complicating efforts to rectify the situation.

Through their investigation, the group identified the CommonCrawl dataset as the likely source of this unfortunate term. This extensive database consists of vast amounts of scraped internet pages, making it exceedingly challenging for researchers outside of major tech companies to effectively address inaccuracies on such a large scale. Furthermore, leading AI companies are notoriously secretive regarding their training data, adding another layer of complexity to the issue.

However, the problem does not rest solely with AI companies. In the world of academic publishing, there are pressing concerns as well. Retraction Watch reported that the publishing giant Elsevier initially attempted to justify the validity of vegetative electron microscopy before eventually issuing a correction. In a similar vein, the journal Frontiers faced its own debacle last year when it was compelled to retract an article containing nonsensical AI-generated images of rat genitals and biological pathways. Earlier this year, researchers from Harvard Kennedy Schools Misinformation Review raised alarms over the proliferation of junk science on platforms like Google Scholar, where unscientific studies often surface amidst legitimate research.

While AI holds genuine potential to advance scientific discovery, its reckless application poses significant risks related to misinformation, affecting both researchers and the scientifically curious public. Once erroneous digital relics become embedded in the internets collective memory, recent studies indicate that they become increasingly difficult to eradicate.