New Research Links Climate Change to the Fall of the Roman Empire

Many historians concur that the decline of the Western Roman Empire, conventionally marked by the fall of ancient Rome in 476 CE, signified the conclusion of classical antiquity. However, there remains considerable debate among scholars regarding the various factors that contributed to the empire's notorious downfall. Among the numerous theories proposed are poor governance, invasions by Germanic tribes, the burgeoning influence of Christianity, population pressures, deteriorating military defenses, and even the unfortunate coincidence of a brief ice age that may have exacerbated these existing challenges.

A recent multidisciplinary study has unveiled new insights into a phenomenon known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age (LALIA), which refers to an ice age that lasted for a comparatively short duration of approximately two to three centuries, commencing around 540 CE. The findings of this research, published on April 8 in the esteemed journal Geology, revealed evidence of rocks in Iceland that had likely been transported from Greenland via icebergs during this chilling period. This significant climatic shift may have played a critical role in the eventual collapse of one of history's most formidable empires.

As Tom Gernon, a co-author of the study and professor of Earth science at the University of Southampton, remarked, This climate shift may have been the straw that broke the camels back in the context of the Roman Empires decline. Climate scientists hypothesize that the LALIA was preceded by volcanic eruptions that spewed ash into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and leading to a substantial drop in temperatures. Such drastic changes in climate might have triggered the mass migrations that were prevalent across Europe during this turbulent era.

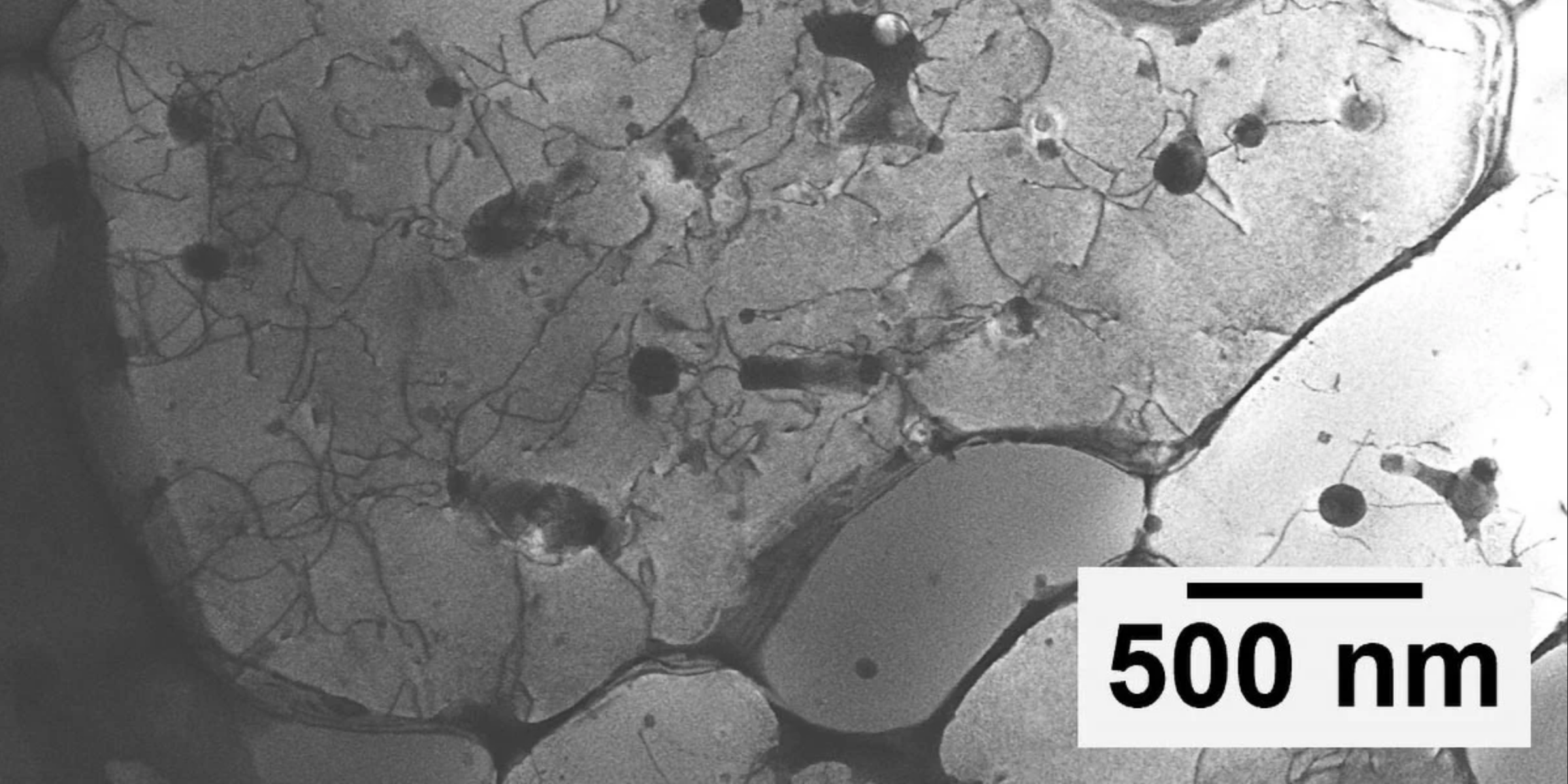

Similar to how the Germanic warriors contrasted with the Roman legionaries, the peculiar rocks examined in this research appeared out of place; the rock types were distinctly different from any currently found in Iceland. Lead author Christopher Spencer, a tectonochemist at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, noted, We didnt know where they came from, highlighting the initial mystery surrounding these geological specimens.

In their quest to uncover the origins of the rocks, Gernon, Spencer, and their co-author, Ross Mitchell from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Geology and Geophysics, meticulously crushed the rocks to analyze the age and composition of tiny crystals known as zircons. Spencer elaborated, Zircons are essentially time capsules that preserve vital information including when they crystallized as well as their compositional characteristics. The combination of age and chemical makeup allows scientists to effectively trace the geological origins of these rocks, akin to forensic fingerprinting.

Through their analysis, the zircon crystals revealed distinct fingerprints pointing to various regions of Greenland spanning periods of 0.5, 1 to 1.5, and 2.5 to 3 billion years ago. This marks the first documented evidence of Greenlandic cobblesrocks about the size of a fistmaking their way to Iceland on drifting icebergs. The researchers proposed that these Greenlandic rocks likely landed in Iceland during the seventh century, coinciding precisely with the Bond 1 event, a known significant episode of ice-rafting during which enormous chunks of ice break away from glaciers, float across the ocean, and subsequently melt, leaving behind debris on remote shores.

Gernon explained, The fact that the rocks come from nearly all geological regions of Greenland provides evidence of their glacial origins. As glaciers shift and move, they erode and break apart various rocks from diverse areas, mixing them chaotically and transporting them, some of which become trapped within the ice.

While historical records do not indicate that ancient Romans ventured into Iceland or Greenland, the ice-rafting event serves as a reminder of the broader climatic upheavals associated with the LALIA that may have further destabilized the Western Roman Empire during its decline. Initially, at the dawn of the Common Era, the Roman Empire enjoyed a warm and stable climate; however, the period from the third to the seventh centuries was characterized by erratic weather patterns that contributed to the spread of diseases and agricultural failures, intensifying existing political and societal tensions.

Its essential to note that while the LALIA commenced more than six decades after the symbolic date of the fall of Rome in 476 CE, its implications on the empires decline are profound. The year 476 CE is often cited as a pivotal moment when the German chieftain Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus, the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire. Nonetheless, Roman cultural influences and societal structures did not vanish instantly. The Late Antique Little Ice Age likely exacerbated the challenges faced by a society already weakened by the loss of its capital.

This recent study not only sheds light on the iceberg activity that transported foreign rocks to Iceland but also serves as a crucial opportunity to reflect on how rapid and dramatic climate changes can disrupt even the mightiest civilizations in history.