The Truth About Life on Other Planets - And Its Implications for Humanity

The quest to uncover the mysteries of existence beyond our own planet is inching closer to a pivotal moment in human history. In a recent development, astronomers have detected traces of a gas on a distant exoplanet known as K2-18b, a gas that on Earth is primarily produced by simple marine organisms. This thrilling discovery raises the tantalizing possibility that we may not be alone in the universe, leading experts to ponder not just the existence of extraterrestrial life, but the profound implications it would have for humanity itself.

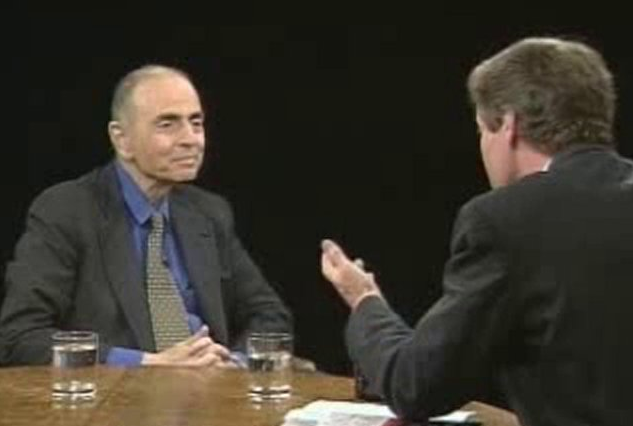

Prof. Nikku Madhusudhan, a leading scientist from the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University, emphasizes the significance of this finding. He states, "This is basically as big as it gets in terms of fundamental questions, and we may be on the verge of answering that question." This revelation prompts further inquiries about how the discovery of life beyond Earth would alter our understanding of ourselves and our place in the cosmos.

Historically, humanity has been fascinated by the prospect of life beyond our planet. In the early 20th century, many astronomers believed they observed linear features on Mars that suggested the presence of advanced civilizations. This belief ignited a wave of imagination, fueling a rich tradition of science fiction that featured flying saucers and extraterrestrial encounters. During a time when geopolitical tensions were rife, particularly concerning communism, depictions of alien visitors often leaned toward the ominous, suggesting that these beings posed a threat rather than offering hope.

Fast forward several decades, and the search for extraterrestrial life has expanded beyond our neighboring planets, Mars and Venus. Recent advancements in astronomy have shifted the focus toward exoplanetsplanets orbiting distant stars. Since the first such discovery in 1992, nearly 6,000 exoplanets have been identified. While many of these new worlds are gas giants like Jupiter, others reside in what astronomers refer to as the "Goldilocks Zone," a region where conditions are just right for life to potentially thrive. Prof. Madhusudhan suggests that there may be thousands of such planets within our galaxy.

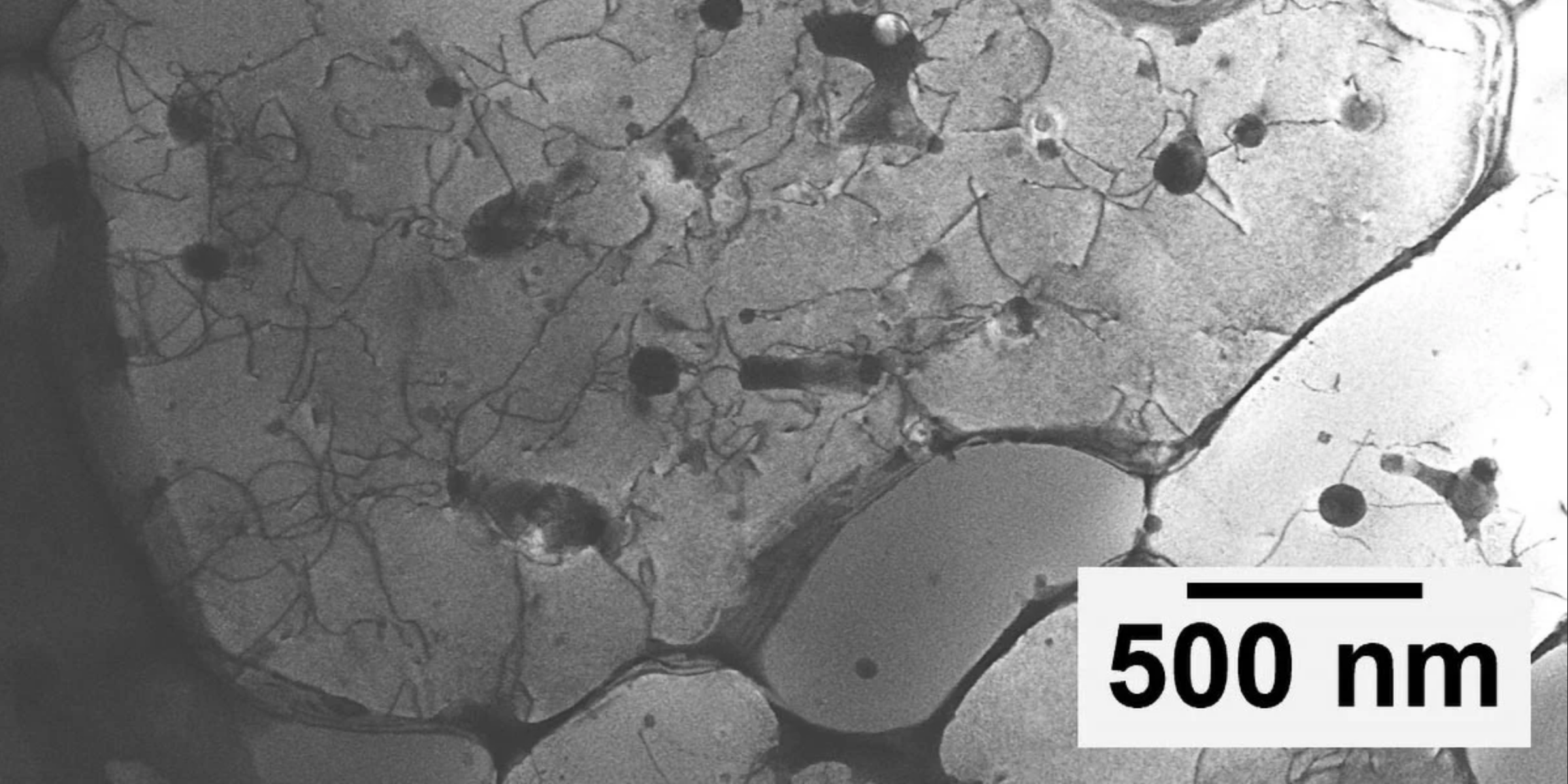

As scientists discover more about these exoplanets, they have developed ambitious technologies aimed at analyzing the chemical compositions of their atmospheres. These efforts involve capturing starlight that filters through the atmospheres and identifying chemical fingerprints, or biosignatures, that indicate the presence of life. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in 2021, is the most powerful instrument of its kind, and it recently made headlines by detecting the gas on K2-18b.

However, despite its groundbreaking capabilities, JWST has limitations. It cannot detect smaller planets or those located too close to their parent stars due to overwhelming glare. To address this, NASA is working on the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), slated for launch in the 2030s, which promises to improve our ability to examine planets similar to Earth. In parallel, the European Southern Observatory is constructing the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile, which will provide unprecedented details of planetary atmospheres thanks to its massive 39-meter mirror.

Looking ahead, Prof. Madhusudhan hopes to gather sufficient data within the next two years to confirm the existence of biosignatures around K2-18b. However, even if he is successful, this discovery would likely spark intense scientific debate over whether these signatures are the result of biological activity or non-living processes.

As further research is conducted and more exoplanetary atmospheres are analyzed, the scientific community is expected to gradually shift toward a consensus that acknowledges the potential for life beyond Earth. Prof. Catherine Heymans, Scotland's Astronomer Royal, believes that continuous observation will enhance our understanding of these distant worlds. She argues that with mounting evidence from various systems, our confidence in the existence of extraterrestrial life will increase.

The idea of discovering life within our own solar system remains incredibly enticing. Robotic missions equipped with portable laboratories could analyze microbial life forms, providing crucial information about the potential for life in harsh environments. The European Space Agency (ESA) is planning the ExoMars rover mission for 2028, intended to drill beneath Martian soil in search of past or present life. Likewise, China's Tianwen-3 mission aims to return samples from Mars by 2031, while NASA is exploring the icy moons of Jupiter for signs of hidden oceans.

While these missions are not designed to find life directly, they serve as preparatory steps for future endeavors. Prof. Michele Dougherty from Imperial College, London, notes the careful considerations that must be made when selecting landing sites on these moons, emphasizing the tedious yet exhilarating nature of this research.

Interestingly, another significant mission is NASA's Dragonfly, scheduled to land on Titan, one of Saturn's moons, in 2034. Titan, known for its lakes and clouds of carbon-rich chemicals, presents a unique environment that could harbor life. With the three essential ingredients for lifeheat, liquid water, and organic compoundsProf. Dougherty expresses optimism about the existence of life on these distant icy bodies.

Despite the excitement surrounding potential discoveries, experts caution that finding simple life forms does not guarantee the existence of more complex organisms. Prof. Madhusudhan contemplates the vast leaps from simple to complex, and then intelligent life, which remain largely unexplained. Dr. Robert Massey from the Royal Astronomical Society echoes this sentiment, emphasizing the complexity of lifes evolution on Earth and whether similar conditions are necessary elsewhere.

As humanity navigates the universe, the prospect of discovering extraterrestrial life could further diminish our sense of specialness in the cosmos. Dr. Massey argues that each astronomical breakthrough has gradually illustrated our displacement in the universe. Contrarily, Prof. Dougherty believes that confirming the existence of even simple life in our solar system would enrich our understanding of our origins and our collective place in the universe.

In this age of unprecedented exploration, scientists are eager to unveil the secrets of life beyond our planet. Many in the field assert that it is not a question of if we will discover alien life, but rather when. Rather than invoking fear, such a discovery could inspire hope and unity among humanity. Prof. Madhusudhan envisions this transformation profoundly altering our worldview, suggesting that upon recognizing the existence of life, we would no longer perceive ourselves as isolated entities but as part of a greater cosmic tapestry, ultimately bringing us closer together.