Colossal Biosciences Aims to Bring Back the Giant Moa Amid Skepticism

Standing over three meters (10 feet) tall, the giant moa is recognized as the tallest bird that ever roamed the Earth. These remarkable, wingless herbivores once dominated the landscapes of New Zealand, consuming vast amounts of trees and shrubs. Their reign ended tragically with the arrival of humans, leading to their extinction only a century after early Polynesian settlers arrived approximately 600 years ago. Today, the legacy of these imposing creatures lives on primarily through Māori oral histories and archaeological discoveries, which include thousands of bones, mummified remains, and the occasional feather.

This week, Colossal Biosciences, a US-based start-up, announced an ambitious plan to resurrect the giant moa, joining the ranks of other extinct species like the woolly mammoth, dodo, and thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger. This announcement has sparked a mix of excitement and skepticism among scientists and conservationists, as many experts doubt the feasibility of bringing back a species that vanished so long ago.

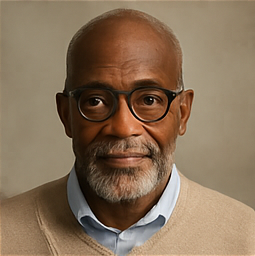

Headquartered in Texas, Colossal Biosciences aims to bring the giant moa back to life within the next five to ten years. This initiative is being pursued in collaboration with the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand. The groundbreaking project reportedly has financial backing from Sir Peter Jackson, the filmmaker known for his work on the Lord of the Rings series, who has invested US$15 million (£11 million) in Colossal and is an avid collector of moa bones. The strategy involves extracting DNA from existing fossilized remains and then employing gene editing techniques on the closest living relatives of the moa, such as the emu. The plan is to hatch these genetically modified birds and introduce them into designated “rewilding sites,” as Colossal envisions.

Sir Peter Jackson expressed his enthusiasm for the project, stating, “The hope that within a few years, we’ll get to see a moa back again – that gives me more enjoyment and satisfaction than any film ever has.”

Māori archaeologist Kyle Davis echoed this sentiment, highlighting the deep cultural connections that Māori have with the moa. He stated, “Our earliest ancestors in this place lived alongside moa, and our records, both archaeological and oral, contain knowledge about these birds and their environments. We relish the prospect of bringing that into dialogue with Colossal’s cutting-edge science as part of a bold vision for ecological restoration.”

Colossal’s ambitious announcements are not without controversy. The company has generated headlines before; in April, it claimed to have brought the dire wolf back to life through genetic modifications of grey wolves, while it also showcased “woolly mice” that were genetically altered to exhibit traits of woolly mammoths. However, many in the scientific community are expressing strong criticism of these claims, arguing that the focus on “de-extinction” distracts from the ongoing, critical loss of global biodiversity. Experts warn that approximately one million species are currently at risk of extinction and that resurrecting species like the moa may not be feasible, especially if their original habitats have changed dramatically.

Critics, including Aroha Te Pareake Mead, a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, argue that the concept of de-extinction is misleading. Mead describes it as a “false promise” and urges that efforts should be more focused on genuine conservation. “These are exercises in the egotistical delight in the theatrical production of ‘discovery’ devoid of ethical, environmental, and cultural considerations. Bring the moa back? To where? To what quality of life? To roam freely?”

Dr. Tori Herridge, an evolutionary biologist from the University of Sheffield who declined an advisory role with Colossal, has pointed out that while creating a genetically modified organism that resembles an extinct species may be possible, it does not equate to truly resurrecting that species. “Is de-extinction possible? No, it is not possible. What you could potentially do is create a genetically modified organism that may contain some traits linked to a previously extinct species based on what we think they were like,” she explained, emphasizing that species behavior is significantly shaped by learned culture.

Colossal Biosciences, however, stands firm in its assertion that its projects might help mitigate the ongoing biodiversity crisis. The company argues that by potentially restoring lost functions to ecosystems through the return of species like the moa or woolly mammoth, they could be making a positive impact. A representative of the firm rejected claims that de-extinction is impossible, asserting their commitment to advancing biodiversity through genetic technology.

Prof. Andrew Pask, who is involved in the moa project, reinforces the idea that skeptics are mistaken. He states, “For many of our living species on the brink of extinction, the damage has been done. They are in an extinction vortex where the population spirals to extinction. The single, only way out of this is by bringing back lost diversity into those species' genomes. This is what de-extinction technology can do.”

Nevertheless, experts like Nic Rawlence, an associate professor of ancient DNA at the University of Otago, remain doubtful about the success of such endeavors. He likened the situation to “Jurassic Park,” suggesting that the chances of successfully reviving the giant moa are exceedingly slim. Rawlence commented, “If we think of the dire wolf, the genome is 2.5 billion individual letters long, and it’s 99% identical to the grey wolf. They made only 20 changes to 14 genes. So, to say they’ve created a dire wolf is farcical. They’ve created a designer grey wolf. And that will be the same with whatever they do with the moa.”