The Legacy of David Hilbert: How the Nazi Regime Altered the Course of Mathematics

In 1934, David Hilbert, a towering figure in German mathematics, found himself dining with Bernhard Rust, the Nazi minister of education. During this tense encounter, Rust inquired, How is mathematics at Gttingen, now that it is free from the Jewish influence? Hilberts poignant response was striking: There is no mathematics in Gttingen anymore. This exchange has become a part of mathematical folklore, a somber tale shared among mathematicians as they reflect on the darker chapters of history.

Hilbert's words encapsulated the devastating impact of the Nazi regime on the University of Gttingen, once a beacon of mathematical brilliance. Its one of the most well-known stories in the history of science, remarks Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, a historian of mathematics at the University of Agder in Norway. He notes that Gttingen had been a dominant force in mathematics on an international scale until the rise of the Nazis.

The year 1933 marked a catastrophic turning point for Gttingen and the broader academic community in Germany. Just two months after Adolf Hitler ascended to the chancellorship, the German government enacted a law that barred Jewsand those categorized as Jewish by the Nazisfrom holding civil service positions. Exceptions were made only for individuals who had served in World War I. The immediate consequences were profound, leading to the ousting of several mathematicians from their positions at Gttingen. By the end of that year, 18 prominent scholars had either left voluntarily or were forcibly removed.

As a result of these events, by the time of Hilbert's notable dinner with Rust, Germany had lost its preeminence in the field of mathematical research. The United States swiftly took its place as the new center of mathematical inquiry. Despite the influence of globalization, America has maintained its status as a leader in the field. Prestigious institutions such as Princeton, Columbia, Berkeley, and Stanford owe much of their development to the European mathematicians who fled to the U.S. to escape the Nazi regime.

In light of a new administration in the United States that seemingly harbors an anti-science stance, scholars are drawing parallels to the historical events surrounding Gttingen as a warning. While Donald Trump is not Adolf Hitler, the lessons from history are profound. Siegmund-Schultze asserts, One also knows from pain that mankind doesnt really learn from history. Otherwise, we wouldnt do all the same foolish things all the time.

The American democratic system is considerably more robust and enduring than that of Germany during the interwar years. However, experts urge caution in noting the similarities. Julia Ault, a historian of German history at the University of Utah, states, What you see in both cases is this disaffection of the lower middle class, suggesting that their perceived loss of status, particularly in comparison to those they view as advancing more rapidly, can create dangerous societal divides.

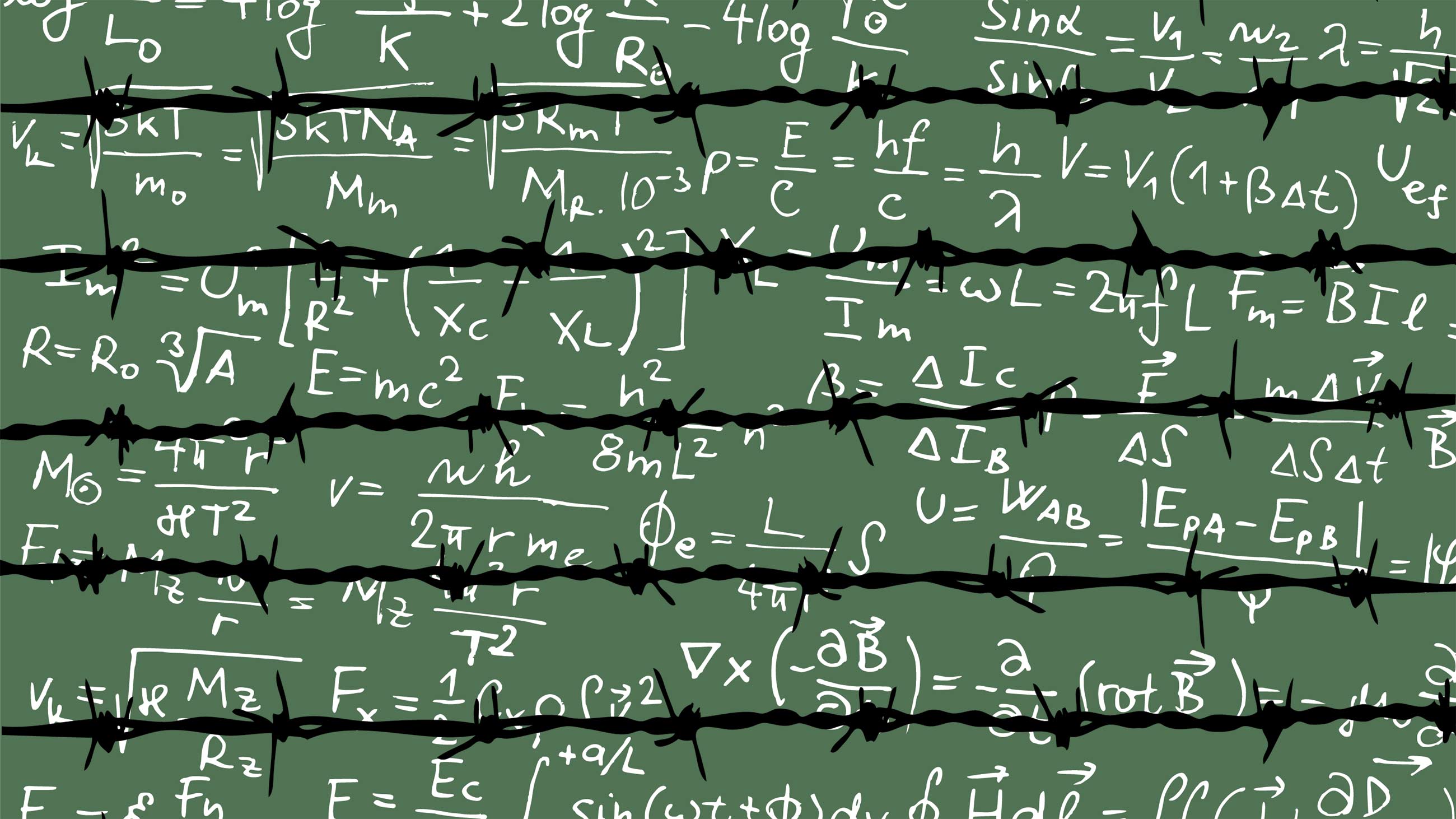

Rather than a blatant suppression of free speech akin to the actions of the Nazis, contemporary scholars express concern about the emergence of a post-truth world, where evidence is disregarded in favor of narratives that align with personal beliefs. Robbert Dijkgraaf, the current director of the Institute for Advanced Study, emphasizes that every scholar is at risk. He notes that the integrity of reasoned argumentation and the pursuit of truthcore values of both science and scholarshipare under threat in todays political climate.

Ault warns that the dismissal of expertise and the rise of populism could have catastrophic consequences, particularly for fields like climate science and environmental protection. Under Trump's administration, scientists feared for their jobs as the administration sought to undermine and silence those studying climate change, which Trump had previously labeled a Chinese hoax. Reports indicated that the administration had imposed a temporary ban on external communication from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and restricted new grants and contracts. Its going to take most of our lifetimes to redo whats going to get undone in the next four years, Ault concludes, underscoring the historical significance of these events.

The legacy of Gttingens fall is not merely a historical curiosity; it serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of academic institutions. Figures such as Carl Friedrich Gauss had helped establish Gttingens mathematical prominence in the 19th century. This legacy continued with renowned mathematicians like Riemann, Dirichlet, and Hilbert, who shaped the trajectory of mathematical research in the 20th century. Richard Courant, who was among those fleeing Gttingen, played a pivotal role in securing funding for a new mathematics institute there, which opened in 1929. However, the richness of this institution was soon to be dismantled.

At the same time, a new haven for mathematicians began to emerge in Princeton, New Jerseythe Institute for Advanced Study (IAS). Founded in 1930 by the Bamberger family, who had successfully sold their department store before the 1929 stock market crash, the IAS was initially envisioned as a medical school free of anti-Semitic policies. However, under the guidance of Abraham Flexner, the institute shifted its focus to basic research in mathematics and science, which proved fortuitous for many Jewish scholars whose careers had been abruptly ended in Germany.

The IAS opened its doors in 1933, operating initially from Princeton Universitys Fine Hall. The timing was fortuitous for numerous displaced scholars. Flexner and the institute's trustees, with the Rockefeller Foundation's support, set out to offer positions to exiled mathematicians and scientists. This effort was met with challenges, as American anti-Semitism persisted, alongside economic concerns regarding high unemployment rates. Flexner had to navigate these complexities delicately, ensuring that each appointment was modest in compensation. However, securing a position at the IAS provided these scholars not only a lifeline but also a foothold in the United States as they sought further employment.

In a 1939 report, Flexner predicted that the center of gravity in scholarship moved across the Atlantic to the United States. His foresight was astute; America indeed benefited tremendously from the influx of talent during this period. Siegmund-Schultze notes that while many developments in mathematics would have occurred regardless, the contributions of Jewish scholars fleeing the Nazis accelerated America's rise as a scientific powerhouse.

Today, we often take for granted the United States' status as a hub for research and scholarship. However, that status was not a given in the 1930s. Dijkgraaf reflects on this history, crediting the generosity of the IAS and its founders with elevating American mathematics. Among the most notable refugees was Albert Einstein, but the institute also welcomed luminaries such as John von Neumann, Kurt Gdel, and Hermann Weyl, whose collective intellect helped shape modern mathematics.

The fragility of institutions is a potent reminder of historys lessons. Just a few months of Hitlers regime unraveled centuries of mathematical progress at Gttingen, leaving a void that Germany would never fully recover from. As von Neumann accurately predicted, the Nazi policies would ruin German science for a generationat least. The American scientific community, benefiting from the contributions of these displaced scholars, stands at a crossroads today. While the existential threats may differ from those faced in the 1930s, the ongoing erosion of support for science and intellectual rigor poses serious risks. It would be a tragic twist of fate if the very fields that flourished due to the influx of German intellectuals were again undermined by ignorance and prejudice.

Evelyn Lamb is a writer based in Salt Lake City. With a background in teaching mathematics and math history at the college level, she has transitioned to full-time writing. Her work has appeared in outlets such as Scientific American, Nature News, the Smithsonian Magazine website, and Slate.