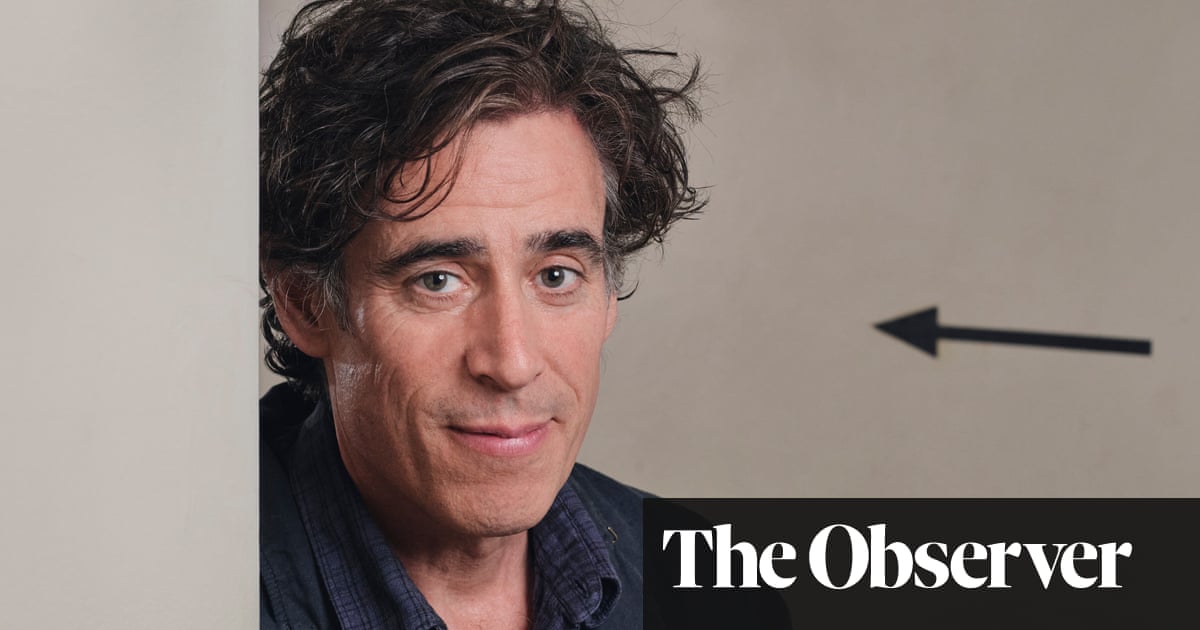

Belarusian Journalist Ksenia Lutskina Reflects on Harrowing Imprisonment and the State of Press Freedom

TALLINN, ESTONIA: Ksenia Lutskina, a journalist from Belarus, has recently been released after serving only half of her eight-year prison sentence, a term handed down after she was convicted of conspiracy to overthrow the government. This conviction came amidst an aggressive crackdown on dissent by President Alexander Lukashenko's regime, which has been characterized by widespread repression of free speech and press rights. Lutskinas sentence was cut short following a troubling health diagnosis; during her pretrial detention, she was found to have a brain tumor, which led to her fainting in her cell.

Upon her release and subsequent relocation to Vilnius, Lithuania, Lutskina shared her harrowing experiences. I was literally brought to the penal colony in a wheelchair, and I realized that journalism has really turned into a life-threatening profession in Belarus, she described to reporters from The Associated Press. Her situation is not unique; she is part of a broader group of journalists who have faced severe persecution in Belarus. Reports indicate that many of these individuals endure brutal beatings, receive inadequate medical care, and are denied the ability to contact lawyers or family members.

According to the organization Reporters Without Borders, Belarus has become the leading European jailer of journalists, with at least 40 currently serving long prison sentences. The Belarusian Association of Journalists has corroborated these numbers, highlighting systemic violations against the press. Lutskina's career took a drastic turn in 2020 when she decided to leave her position producing documentaries for the state broadcaster. This decision coincided with mass protests ignited by an election widely condemned as fraudulent, which ultimately allowed the authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko to maintain his grip on power. As part of her efforts to foster an independent media landscape, Lutskina attempted to establish an alternative TV channel aimed at fact-checking government narratives. However, this endeavor led to her arrest and conviction.

The situation for journalists in Belarus has continued to deteriorate, compelling many to flee the country of 9.5 million, where they now operate from abroad. However, the challenges persist; an increase in restrictions, particularly following the withdrawal of US foreign aid during Donald Trumps administration, has put many independent media outlets on the brink of collapse. Andrei Bastunets, chairman of the BAJ, expressed his concerns to AP, stating that journalists are not only subjected to domestic repression but also face dire financial strains due to the loss of crucial funding.

The crackdown that began in 2020 in response to the disputed elections has resulted in over 65,000 arrests, with thousands recounting stories of police brutality. Opposition figures have been jailed or forced to seek asylum outside the country, while hundreds of thousands have fled due to fear of persecution. Rights group Viasna reports that there are more than 1,200 political prisoners behind bars, including notable figures like Ales Bialiatski, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

Independent media are under siege; many outlets have been shut down or outlawed entirely. For over three decades, Lukashenko has dismissed independent journalists as enemies of our state and has publicly stated that those who have fled will not be allowed to return. The environment for journalism has become increasingly dire; according to Bastunets, the raids, arrests, and abuse faced by journalists have escalated to an absurd level, with families of journalists often threatened. There have been instances where families of targeted journalists requested rights organizations to abstain from discussing their cases publicly to avoid further retaliation.

Every month seems to bring fresh arrests and raids, a trend that has nearly eradicated independent journalism within Belarus. This repression even extends to those who shift their focus to non-political topics; in December, the entire editorial team of Intex-press, a popular regional news outlet, was arrested and charged with assisting extremist activity. The term extremism has become a common label used by authorities to detain and jail those who dare to criticize the government. Even consuming content from independent media deemed extremist can lead to short-term imprisonment. The websites of these outlets are systematically blocked, further limiting access to independent news.

Reporters Without Borders has documented that 397 Belarusian journalists have faced what they classify as unjust arrests since the onset of the crackdown in 2020, some of whom have been detained multiple times. Approximately 600 journalists have sought refuge abroad, yet many continue to experience harassment from Belarusian authorities, who can initiate cases against them in absentia, put them on international wanted lists, or seize their properties in Belarusian territory. Additionally, relatives of these journalists frequently become targets for intimidation.

In a significant development, Reporters Without Borders has filed a lawsuit with the International Criminal Court, accusing Belarusian authorities of crimes against humanity, citing instances of torture, beatings, wrongful imprisonment, and the forced displacement of journalists.

Among the journalists currently imprisoned is Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, who was arrested while covering the 2020 protests. Initially sentenced to two years for public disorder, her sentence was later extended to over eight years on charges of treason. Her husband, Ihar Iliyash, a political analyst, is also imprisoned. The conditions in which these journalists are held are often dire; Bakhvalava has been placed in solitary confinement multiple times and reportedly endured physical abuse while incarcerated. A former inmate relayed that during one incident, guards beat her while she pleaded for medical assistance.

Another prominent case is that of Andrzej Poczobut, a correspondent for Gazeta Wyborcza and a significant figure in the Union of Poles in Belarus. He was convicted of harming Belarus national security and sentenced to eight years in prison, where he has faced numerous health issues. Despite interventions from the Polish government, Poczobut has remained in solitary confinement, which is often described as the harshest form of imprisonment. His situation remains critical, and he has publicly refused to seek a pardon from Lukashenko.

Maryna Zolatava, who served as the editor of Tut.By, Belarus' most popular online news platform before its closure, was sentenced to 12 years for inciting actions considered harmful to national security. These cases highlight the ongoing struggles faced by journalists in Belarus, where Lukashenkos regime appears to view political prisoners as instruments to be bargained with in the international arena. Analysts suggest that Lukashenko is exploiting the release of some political prisoners to forge better relations with the West, which may include easing economic sanctions.

Since the controversial January election that allowed Lukashenko to extend his rule for a seventh term, he has pardoned over 250 individuals, which analysts believe is part of an effort to improve international relations. In a calculated move, he previously released several individuals, including journalists from US-funded news outlets, in a bid to showcase a willingness to engage with the West. Still, many journalists remain behind bars, coerced into making regrettable public statements against the government.

Ksenia Lutskina, who has now sought refuge in Lithuania with her 14-year-old son, reflects on her experience and the state of her homeland. They have both read George Orwells dystopian novel 1984, which is banned in Belarus, and have noted striking parallels to their own experiences. Belarus has turned into a gray country under a gray sky, where people are afraid of everything and speak in whispers, she remarked. Despite her traumatic imprisonment, Lutskina conveyed that she felt less fear in prison than she perceives in those who remain in Belarus. She described how many people live with their heads down, too frightened to confront the stark realities of life under an oppressive regime.