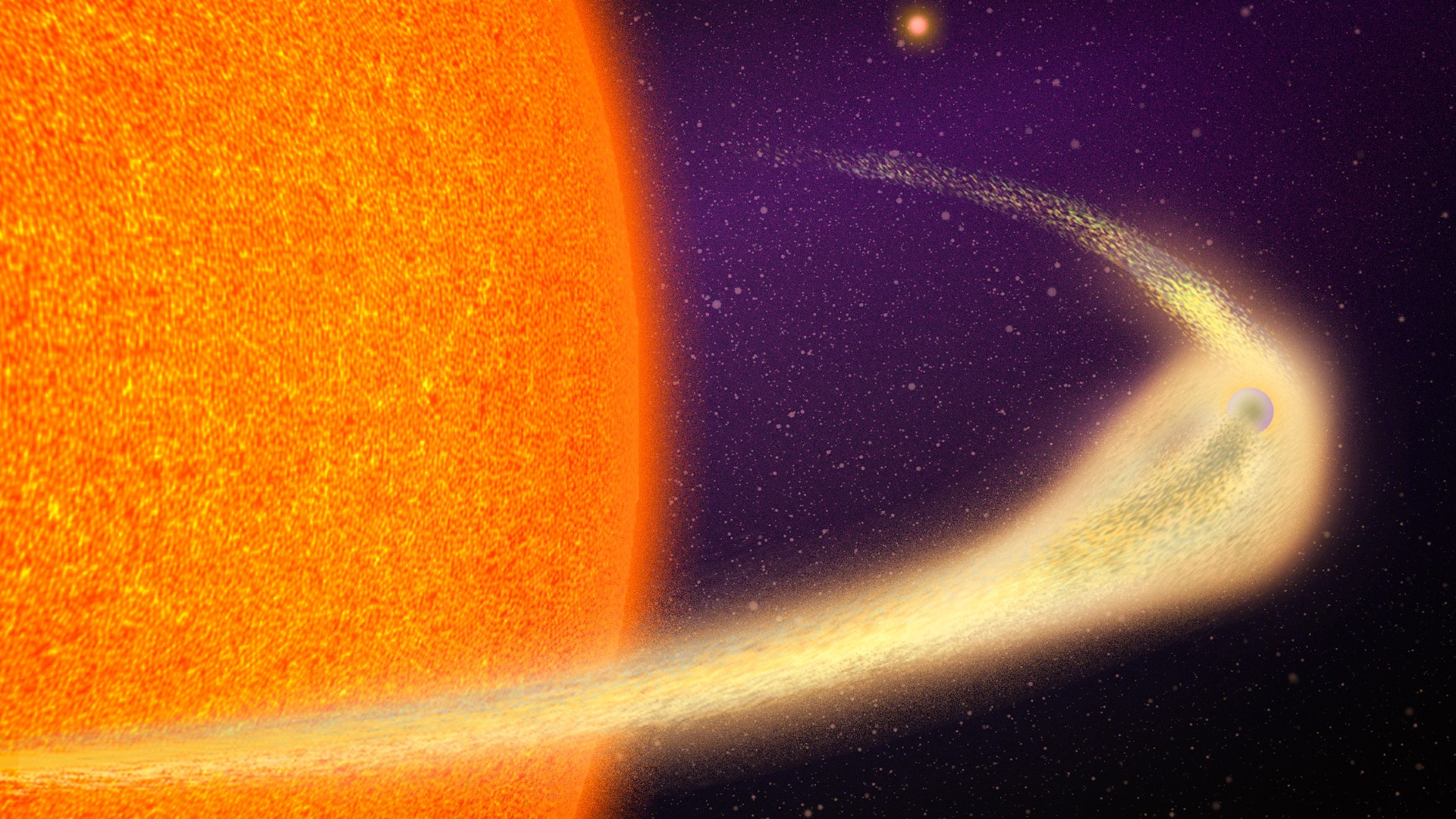

Astronomers discover doomed planet shedding a Mount Everest's worth of material every orbit, leaving behind a comet-like tail

Scientists have discovered a planet that is literally falling apart as it orbits its star. Located about 140 light-years from Earth in the Pegasus constellation , this doomed world named BD+05 4868 Ab whips around its star once every 30.5 hours — so close that its surface is being scorched into magma and vaporizing into space. With each orbit, BD+05 4868 Ab leaves a blazing trail of molten rock behind it like a comet made of lava, offering a rare glimpse of an exoplanet in the final stages of its destruction. What's even more astonishing: with every blistering 30-hour orbit — which heats the planet to close to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,600 degrees Celsius) — the planet sheds as much mass of molten rock as an entire Mount Everest. "The extent of the tail is gargantuan, stretching up to 9 million kilometers long, or roughly half of the planet's entire orbit," said Marc Hon, a postdoc in MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research in a statement. This is an epic disintegration unfolding in real time, and the team predicts that it might take 1 to 2 million years for the entire planet to fully disintegrate. "We got lucky with catching it exactly when it's really going away," said Avi Shporer, a collaborator on the discovery who is also at the TESS Science Office. "It's like on its last breath." Only three other disintegrating worlds have been identified among the more than 6,000 discovered exoplanets — each leaving a distinctive, comet-like tail of debris behind it. But BD+05 4868 Ab stands out: its tail is the longest of them all. "That implies that its evaporation is the most catastrophic, and it will disappear much faster than the other planets," Hon said. Because BD+05 4868 Ab orbits so perilously close to its star, its transit — the dip in starlight created as the planet passes in front of its star — appears especially bright and distinct. The planet was discovered with NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) observatory. TESS, which scans nearby stars for periodic dips in brightness, revealed a strange, fluctuating transit that stood out from the usual planetary candidates. Get the Space.com Newsletter Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more! Contact me with news and offers from other Future brands Receive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsors This makes it an ideal target for NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, whose sensitive instruments can capture subtle changes in starlight to identify the chemical makeup of the vaporized rock trailing behind the planet. The result is a rare opportunity to watch a planet disintegrate in real time, and to study the composition of a world being stripped down to its core. Hon says the discovery was a lucky break. "We weren't looking for this kind of planet," he explained. "We were doing the typical planet vetting, and I happened to spot this signal that appeared very unusual." Though BD+05 4868 Ab's transit appears every 30.5 hours, the star's brightness took much longer than in other instances to return to normal. Even more bizarre was the depth the starlight's dip changed with every transit. "The shape of the transit is typical of a comet with a long tail," Hon explained. "Except that it's unlikely that this tail contains volatile gases and ice as expected from a real comet — these would not survive long at such close proximity to the host star. Mineral grains evaporated from the planetary surface, however, can linger long enough to present such a distinctive tail." Shporer explains that the planet is likely falling apart due to its low mass. "This is a very tiny object [between the size of Mercury and the moon], with very weak gravity, so it easily loses a lot of mass, which then further weakens its gravity, so it loses even more mass," Shporer stated. "It's a runaway process, and it's only getting worse and worse for the planet." The team plans to carry out follow up observations this summer using the JWST. "This will be a unique opportunity to directly measure the interior composition of a rocky planet, which may tell us a lot about the diversity and potential habitability of terrestrial planets outside our solar system," Hon said. And in the meantime, the researchers said they're looking for more examples in TESS data. "Sometimes with the food comes the appetite, and we are now trying to initiate the search for exactly these kinds of objects," Shporer said. "These are weird objects, and the shape of the signal changes over time, which is something that's difficult for us to find. But it's something we're actively working on."