‘I love humans - it gives me the courage to approach them’: the disarming work of Mao Ishikawa

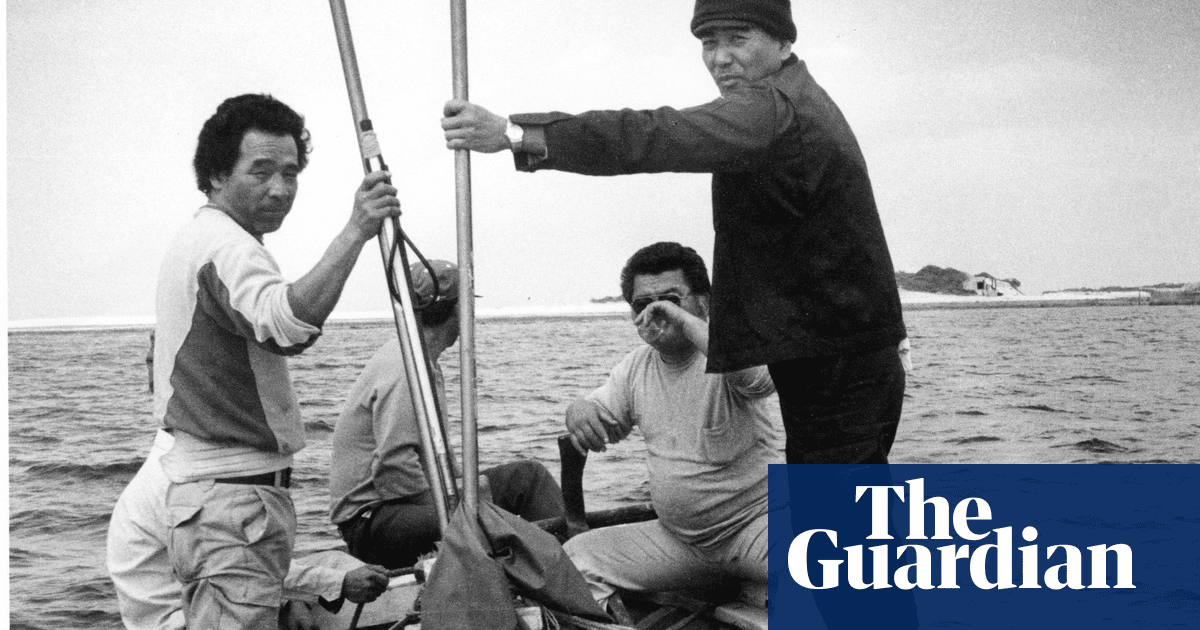

In 1975, when Mao Ishikawa was in her early 20s, she took a job in a bar frequented by Black American GIs stationed at Camp Hansen, in Okinawa. She had grown up hating the Americans who controlled her home island and, to this day, maintain military bases there. Yet she found kindred spirits among the soldiers and her fellow barmaids, with whom she lived and loved and also photographed. These images became her first major documentary series, Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa, and capture a sense of their youthful freedom and outsider bonhomie, from the group of men and women hanging out in bed to the trio hitting the town for a night out, the women’s hair teased into afros, massive hoop earrings glinting. Like much of what you can discover in Ishikawa’s first UK survey, spanning her five-decade career – from dockworkers to travelling actors or downtown Philadelphia’s African American community – these are natural, intimate photographs of a hidden world that could only have been taken by an insider. They are an act of political resistance, too. Ishikawa explains how her antipathy towards the American colonisers was inevitable during a period when everything was “rotten and collapsing”. The US had been an oppressive presence in Okinawa since the aftermath of the second world war. Though governance of the island was returned to Japan in 1972, military bases remained, serving as a stop-off for returning troops during the Vietnam war and as a deterrent to a potential threat from China. When Ishikawa came of age, crimes committed by soldiers against Okinawans, including an alarming number of sexual assaults, were tried in military courts, with suspects frequently acquitted and discharged. Okinawa had apparently been discarded by Japan, and both Americans and the Japanese, she says, saw Okinawans as “less than human”. Taking a photograph of someone in an intimate moment only happens after I’ve spent time with them, and always with permission “It made me passionate,” she says. “I have a lot of anger; sometimes it surprises people, but it’s my motivation as well.” When Ishikawa turned her lens on barmaids and American soldiers, she’d recently returned from a brief stint in Tokyo where she’d attended the new photography school set up by Shomei Tomatsu, a driving force behind the medium’s golden age in postwar Japan who would later champion her work. Her studies weren’t curtailed by a lack of focus. She wanted to pursue the one subject that really mattered to her, documenting Okinawa’s overlooked. Like the chronicler of the New York underground, Nan Goldin, to whom she’s been compared, Ishikawa gets involved in what she catches on camera, describing it once as her own “emotional record”. Where this immersive method has taken her is a continual surprise. A Port Town Elegy, the project that emerged a decade after Red Flower, focused on some of Okinawa’s most intimidating figures: burly dockworkers who lived fleeting lives of long fishing tours, money blown in brothels, constant fights and time in and out of jail. “They were fierce-looking, like yakuza gangsters,” she recalls. “They had a very closed community and people feared them though I always have an urge to explore what seems offputting or unknown.” When it comes to Ishikawa’s talent for overcoming barriers and capturing authentic experience, one series particularly stands out. Life in Philly, focused on African Americans in Philadelphia in 1986, is testament to the trust she establishes with her subjects. It captures an everyday world, including people lying around naked, in the aftermath of sex. She explains: “Taking a photograph of someone in an intimate moment would happen only after I’d spent a lot of time with them, and always with permission. You might think I’m a bold person, but I’m also very sensitive. I love humans. That’s my main drive, and it gives me the courage to approach them.” Mao Ishikawa is at Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry, 1 May to 22 June. Five highlights of the exhibition A Port Town Elegy, 1983–86 (main picture) Ishikawa ran a pub where she got to know Okinawa’s stevedores, one of whom became her partner. She began photographing this distinctly man’s world at a little house where they’d drink all day. If they started to fight, Ishikawa just kept shooting quietly. Her images give a rare insight into their existence, balancing the grit with companionship and release. View image in fullscreen Uchinaa Shibai (Okinawan Play): A Story of Nakada Sachiko's Theater Company (1977- 1992). Photograph: Mao Ishikawa Uchinaa Shibai (Okinawa Play): A Story of Nakada Sachiko’s Theater Company, 1977–92 Ishikawa spent years photographing the traditional Okinawan theatre company Diego-Za on stage and behind the scenes. She was so moved by their struggle to keep the island’s traditional culture alive she offered to abandon photography and join the troupe. “They gently rejected me,” she laughs. skip past newsletter promotion Sign up to Inside Saturday Free weekly newsletter The only way to get a look behind the scenes of the Saturday magazine. Sign up to get the inside story from our top writers as well as all the must-read articles and columns, delivered to your inbox every weekend. Enter your email address Sign up Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy . We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. after newsletter promotion View image in fullscreen Mao Ishikawa, Life in Philly (1986). Photograph: Mao Ishikawa Life in Philly, 1986 In one sense, this series which focused on the African American community around Ishikawa’s old friend, ex-soldier Marlon James, in Philadelphia, marked a literal departure from Ishikawa’s usual turf. Yet it continues her interest in the underrepresented and overlooked. View image in fullscreen Mao Ishikawa, Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa (1975-1977). Photograph: Mao Ishikawa Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa, 1975-77 Ishikawa planned to photograph US soldiers rather than Black soldiers per se, when she landed a job in a bar catering to African Americans. She let circumstances lead her where they would: “I’ve always sided with those who are weaker. I saw how the Black soldiers were bullied by the whites. Not that these guys didn’t fight back. There were fights in the street that we’d all cheer.” View image in fullscreen Mao Ishikawa, Okinawa and the Japanese Self- Defence Forces (1991- 1995, 2003). Photograph: Mao Ishikawa Okinawa and the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, 1991–95 Working for the Okinawa Times, Ishikawa was granted rare access to photograph inside the local base of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, a controversial presence in the supposedly demilitarised country. Her images of children with soldiers’ guns, taken during a day when families were welcomed to a base, drew condemnation for the forces’ indoctrination of the young.