New Research Uncovers Secrets of Extinct Giant Kangaroos

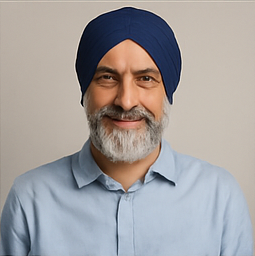

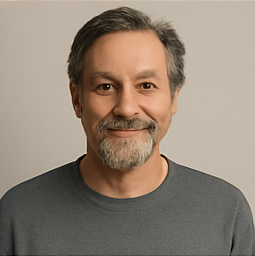

A groundbreaking study published in the esteemed science journal PLOS One has revealed intriguing insights into the behavior and habitat preferences of the extinct megafauna, particularly the giant kangaroo known as Protemnodon. Lead researcher Chris Laurikainen Gaete, affiliated with the University of Wollongong, spearheaded the research, which posits that these ancient creatures were surprisingly less mobile than their modern relatives, often remaining in limited territories.

The research team meticulously examined fossil records from Mount Etna, Queensland, where these magnificent creatures once roamed the Australian outback more than 300,000 years ago. Despite the giant size of these kangaroos, which could stand up to two meters tall, they apparently maintained smaller home ranges than previously anticipated. This newfound understanding raises crucial questions about how these animals adapted to their environment and the factors contributing to their eventual extinction.

Traditionally, it has been understood that larger herbivores tend to travel farther in search of food, a behavior exhibited by many modern kangaroo species. However, this study challenges that assumption, suggesting that the Protemnodon were more sedentary, primarily foraging within a confined area of their rainforest habitat. Laurikainen Gaete stated, This idea of home range is pretty important, because your dispersal capacity will dictate your vulnerability to extinction should something change in your environment.

During their research, the team analyzed isotopes found in the teeth of fossilized giant kangaroos, which provided insights into their foraging patterns over a substantial period. The expectation was that these creatures would exhibit high mobility based on their size. However, the results indicated a surprising tendency for them to remain anchored in the same geological substrate where their remains were discovered.

Historically, the Mount Etna region was characterized by a stable rainforest ecosystem, which provided an abundance of resources for these giant kangaroos. We know that at this point in time, they lived in a rainforest habitat, Laurikainen Gaete explained. But as the climate changed, these small home ranges predisposed them to extinction, meaning they couldn't traverse longer distances to find food during the transition to a more arid environment.

This period of climatic upheaval, occurring approximately 280,000 years ago, marked a significant shift as the lush rainforest was replaced by tougher, dry-adapted flora that rendered resources more sparse and difficult to find. The study highlights the precarious balance that these ancient creatures had to navigate, emphasizing the role environmental changes played in their decline.

The research team was a collaborative effort involving multiple academic institutions, including the University of Wollongong, the University of Adelaide, Queensland Museum, and Monash University. This collective approach underscores the importance of interdisciplinary research in uncovering the complexities of prehistoric ecosystems.

In reflecting on the broader implications of this study, Laurikainen Gaete noted that the methodologies developed to explore the Protemnodon species could serve as templates for understanding other extinct species within Australias unique megafauna. The Australian ecosystem was once dominated by megafauna, but nearly all these species eventually died out, and there remains no clear consensus on the reasons why.

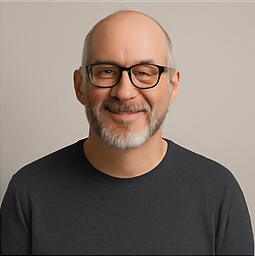

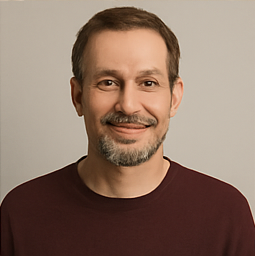

In agreement with Laurikainen Gaete's findings, experts like Isaac Kerr from Flinders University emphasized the significance of this research in the context of global scientific exploration. Kerr, whose own research has led to the identification of three new species of extinct kangaroos, remarked, In Australia, we are only starting to scratch the surface of understanding the complexities of our fossil fauna.

This new understanding of the Protemnodon and other megafauna will not only illuminate past ecological dynamics but may also provide critical lessons relevant to contemporary conservation efforts. The study highlights how understanding historical responses to environmental shifts can inform current strategies to protect vulnerable species facing similar challenges today.