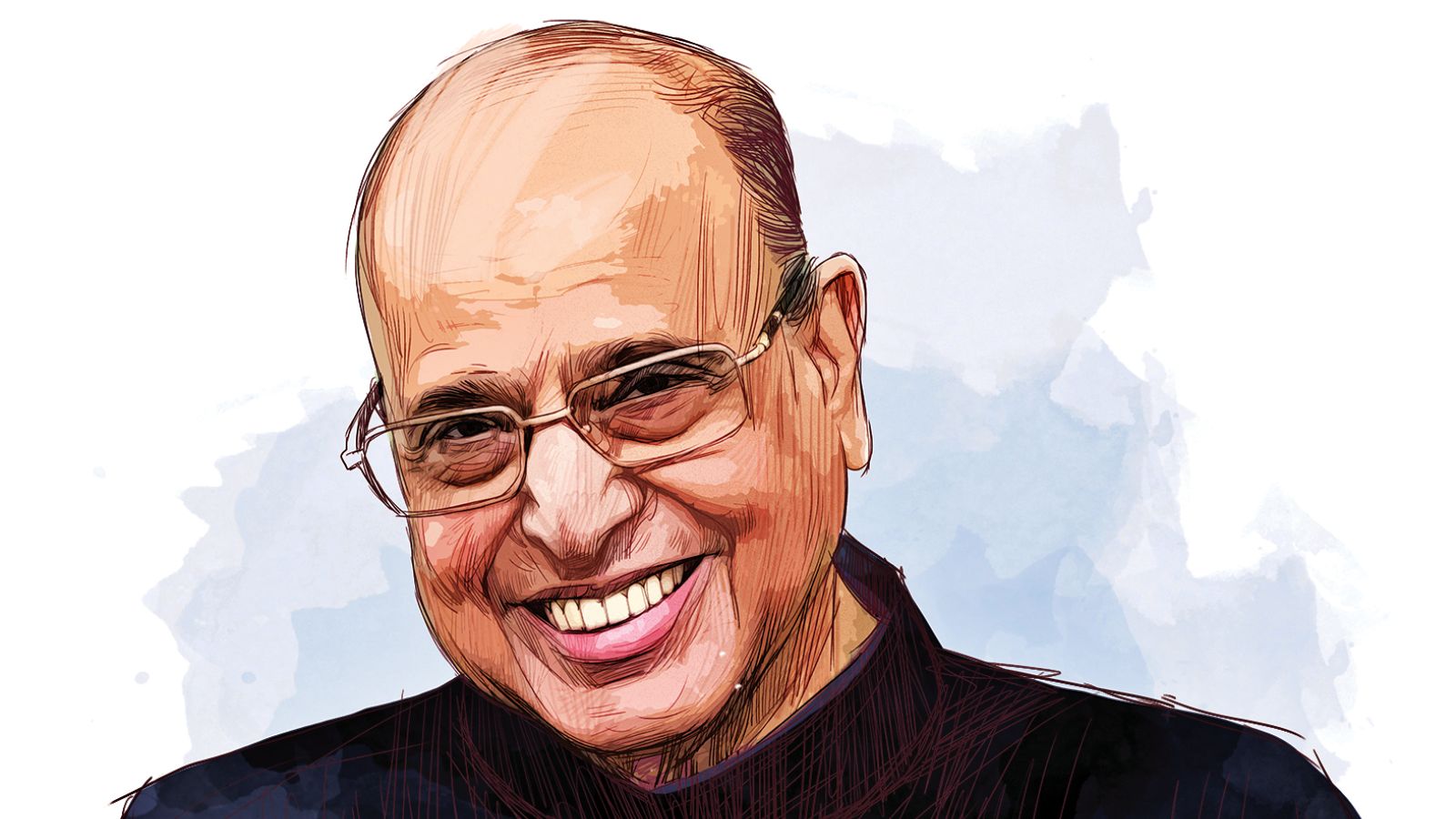

Dr K Kasturirangan (1940-2025): Visionary scientist who dreamed big, steered ISRO through tough times

Chandrayaan-3 was scheduled to make its landing on the Moon on August 23, 2023. A day earlier, The Indian Express had reached out to K Kasturirangan, the charismatic former chairman of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), seeking an interview to mark the occasion. Having suffered a heart attack a month ago, and not in the best of health, Kasturirangan was reluctant, and sent a message that the best he would be able to do would be to send a few lines of written responses. But a day later, just ahead of the landing, he indicated that he would like to talk, and appeared on a video call from his Bengaluru home where he was recovering. “I have not been keeping well, and did not want to do interviews. But you have asked a very interesting question about Vikram Sarabhai, and I wanted to talk about this. After all, I am amongst the last few remaining who is proud to have known and worked closely with Sarabhai,” Kasturirangan said, and went on to have a conversation that went on for more than half an hour. Story continues below this ad Kasturirangan, a celebrated space scientist who also served as member of Rajya Sabha and a member of the erstwhile Planning Commission, passed away in Bengaluru on Friday morning. He was 84, and ailing for the last two years due to age-related complications. His condition had deteriorated last month, and he had been under palliative care at home. The question that had aroused his interest on the Moon-landing day related to Sarabhai, widely considered the father of India’s space programme, and a man he admired deeply. Former Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh, in his tribute, wrote that Kasturirangan would often tell him how profoundly he had been impacted personally and professionally by Sarabhai and Satish Dhawan, another space stalwart. Sarabhai also happened to be the teacher under whom Kasturirangan completed his PhD, in cosmic X-rays, at the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad. Sarabhai, while talking about the role of space programme in a developing country like India way back in 1968, had famously remarked that he did not have the “fantasy” of India competing with other advanced nations in the exploration of Moon, other planets, or manned missions, and would much rather see ISRO working for the benefit of common people, and help in providing solutions to the country’s problems. Story continues below this ad When asked if ISRO was finally diverging from Sarabhai’s vision now that it not only had a full-fledged exploration programme but was also planning to send humans into space, Kasturirangan had said, “I am glad you asked this. And this is important to understand the role that India’s space programme plays. It is true that Sarabhai saw space technologies as a tool to fulfil India’s developmental requirements. He was of the view that in a developing country like India, space technology could ensure optimal utilisation and management of the limited resources. He used to forcefully argue that timely, accurate and precise information about our critical resources was essential. We had primitive communication systems at the time. We needed massive improvements in education and health systems. We needed good information in meteorology which could predict rains so that we could plan our agricultural activities. With his passionate advocacy, he managed to convince the government to invest in space technology. And thus, India became the only country — probably Japan was another — to start a space programme with an entirely peaceful approach to uses of space technology, and focussed totally on developmental needs,” Kasturirangan had said. “Sarabhai unfortunately died in 1971 but all his successors at ISRO, Prof MGK Menon, Satish Dhawan and U R Rao, continued to work on his vision. ISRO built capabilities in remote sensing, communication, broadcasting, meteorology, earth observation, satellite technologies. By the time U R Rao left office (in 1994), much of Sarabhai’s vision had already been realised,” he said, arguing that the logical next step in carrying forward Sarabhai’s legacy was to utilise the capabilities built in the previous three decades. The foray into space exploration thus was an obvious choice. “India’s space programme is still serving the country, and its people. In many more ways now, because of our enhanced capabilities,” he said. Story continues below this ad Kasturirangan himself had a pivotal role to play in the transformation of ISRO into a formidable space exploration agency competing with the best in the world. It was during his nearly decade-long leadership of the organisation (1994-2003) that the Moon mission was conceived, and the first conversations on a possible human spaceflight were laid on the table. In the book ‘Space and Beyond’, Kasturirangan revealed that in the proposal put forward to the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, he and his colleagues had named the lunar programme as ‘Somayaan’. It was Vajpayee who changed it to ‘Chandrayaan’ since he considered it more apt. Kasturirangan has also written that at the Indian Science Congress event in 2003, Vajpayee had asked him about the possibility of sending humans into space. He had told Vajpayee that it was possible but would take some time. Kasturirangan guided ISRO during a rather tumultuous period. This was the time when India faced tight international controls on technology, which became worse after the 1998 nuclear tests. India had been denied the crucial cryogenic technology without which a well-developed space programme could not be built. It was during Kasturirangan’s time that ISRO embarked on self-reliance and indigenisation, which delayed the programmes a bit but eventually paid off handsomely in creating in-house capabilities. Kasturirangan also had to deal with the infamous spy scandal case, one of the worst crises that ISRO has faced. After his retirement from ISRO, where he served for more than three-and-a-half decades, Kasturirangan was nominated to Rajya Sabha by the Vajpayee government in 2003. After that stint was over, the Manmohan Singh government appointed him as a member of the Planning Commission in 2009 where he served till the change of government in 2014. Story continues below this ad He headed two committees whose reports have led to major policy changes. His report on the ecology of the Western Ghats, essentially a review of an earlier report by a committee headed by environmentalist Madhav Gadgil, is the basis on which human activities in specific areas of the Western Ghats are sought to be regulated. Kasturirangan also headed the committee that recommended the New Education Policy.