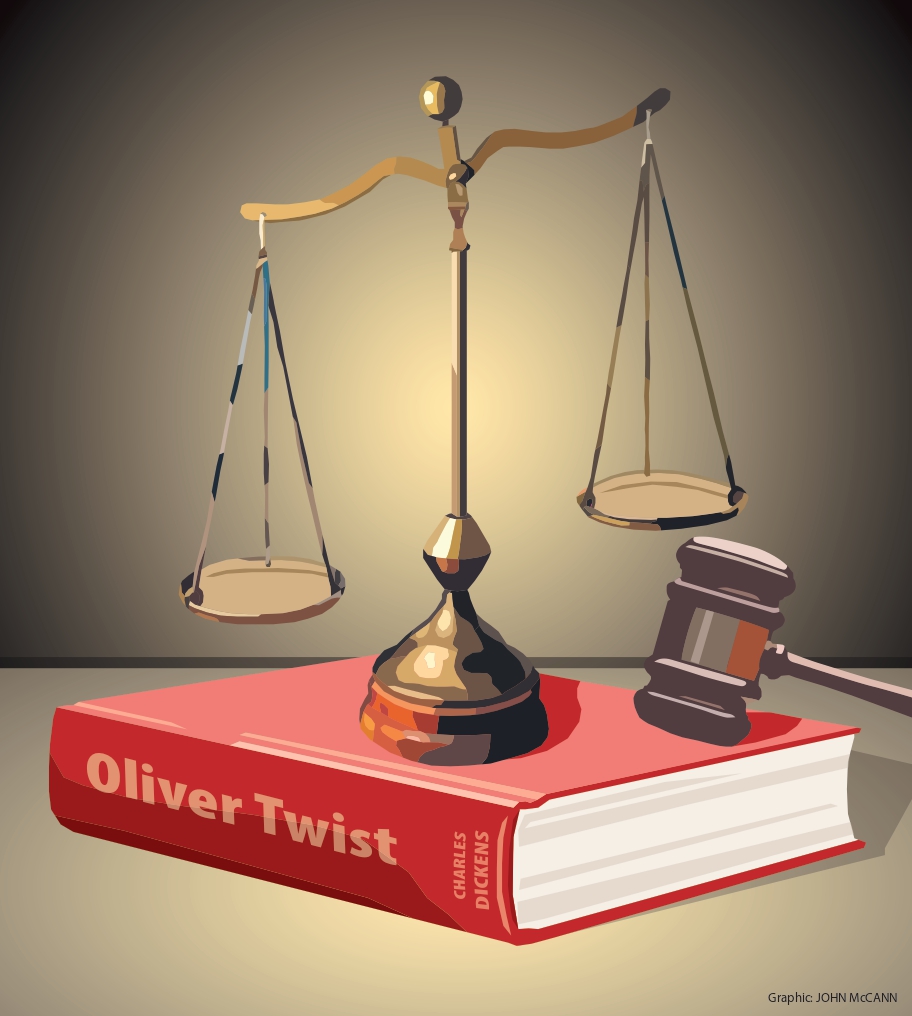

Is the law indeed an ass in this case?

If it were to be established that the law is indeed as dumb as an ass, as suggested by English writer Charles Dickens in his 1838 novel Oliver Twist, what would society think? Second, how does this understanding fit into the “fit and proper” paradigm sought by the Legal Practice Council, when it admits legal practitioners to practise law? I prefer to use the lens of this analogy — “the law is an ass” — to understand the recent decision by the council to investigate Dali Mpofu, SC, for alleged impropriety or breach of its code of conduct. The ass — in the Dickensian world, a place characterised by squalor, poverty and social injustice — was known to be the dumbest creature under the sun. Its obstinacy in not doing what it was ordered to do was thought of as legendary. Dickens, with his critical political mind, as we also saw in his masterpiece A Tale of Two Cities, makes it clear that the law becomes “an ass” when its application is rigid and not applied in keeping with prevailing conditions affecting the poor and oppressed. To drive home his point, he makes an example of Oliver, the young title character of the novel, who had experienced a difficult upbringing, but his need was overlooked by the cruel and unjust system. We must, then, even today, as Dickens suggested a couple of hundred years ago, infer that evil and unjust law practitioners are antithetical to what the “fit and proper” dictum connotes. Bad legal systems, adorned with repressive and unjust legislation, in many ways unconstitutional — and lacking respect for others — should be rejected by communities, as the apartheid system was in this country. The implications for the law, as for the “fit and proper” paradigm, are stark when we turn a blind to an injustice. The “fit and proper person” requirement in South African law is a key criterion for admission — and readmission — to the legal profession. The would-be legal practitioner ought to pass the litmus test — the assessment of character, integrity and suitability — and, to top it all, to be above reproach. The law has to ensure that all, and not some, are treated as fairly as it is humanly possible without regard to status, that all should be seen to be equal before the law, and that to receive justice is to be aspired to. Most tellingly, if the law is to escape community censure and judgment, it has to be seen as even-handed, not favouring a few and acting harshly against others, particularly vulnerable communities. Which brings me to this fact — officers of the court, which is to say, advocates and attorneys, among others, ought to be advocates for the legal system of which they are a part to be just. Politicians, most of the time, tend to pervert the system for their own nefarious reasons. Not so long ago, chief whip and member of parliament of the uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) party Mzwanele Manyi told his colleagues that, if his party were to form a government it would scrap the constitutional framework as we know it today and revert to parliamentary sovereignty. This view is shared by the MK party parliamentary leader John Hlophe, a former judge, and someone expected to have a comprehensive appreciation of constitutionalism. Parliamentary sovereignty is a throwback to the apartheid-conceived 1961 Constitution. It stipulates that parliament “shall be the sovereign legislative authority in and over the Republic, and shall have full power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the Republic”. “[That]no court of law shall be competent to enquire into or to pronounce upon the validity of any Act passed by Parliament …” This must then mean that the MK party, like the National Party that came to power in 1948, aligns itself with the arrangement by which the apartheid government used the parliamentary supremacy at its disposal “as a powerful instrument to secure power for the white minority”. Supposing the MK party were to have its way, win elections and run the government, the implications for constitutional democracy seem dire. Spelled out clearly, this would mean that unconstitutional laws and provisions could find themselves passing constitutional muster. This would be to revert to the principle of the supremacy of the legislature, an obnoxious legal principle at odds with the notion of constitutional supremacy that holds that the Constitution is the ultimate legal authority. The principle of supremacy of the legislature would mean that the courts would be stripped of testing authority to determine, using the Bill of Rights, the constitutionality of laws passed by parliament. The country would be back to old ways, as it was in the apartheid years, where the government rammed down the throats of black citizens legislation that infringed on their rights. Now back to the “fit and proper” principle and the question of whether the law is an ass. Lawyers take an oath or make a declaration upon being admitted to the legal profession. This includes a pledge to uphold the law, act with integrity and be a “fit and proper” person to practise law. With that said, practitioners are the face of the legal system, and are duty-bound, by the fact that they have taken an oath, to strive to be “fit and proper”, to help guard against the perversion of the system by unscrupulous actors. Could the so-called bad apples of society, if charged with crime in the court of law, be assumed innocent, however reprehensible their public record might suggest they are? The law would be an ass if, without sound evidence, it found any person guilty, simply because of their shady past. Judges know this. And that is why they give deference, and assign no guilt, to suspects who are brought before them. In the end, it ought to be the lawyers, as officers of the court, who help the bench come to an appropriate decision — helping to show that the law is far from being an ass. Dickens, in Oliver Twist, uses the phrase “the law is an ass” to draw a parallel between its inflexibility and the “mythical obstinacy of donkeys”. In legal contexts, a “fit and proper person” refers to someone deemed to be suitable to hold a specific position or role, particularly within the legal profession. This phrase is commonly used in relation to lawyers, signifying that they possess the necessary qualities, character and integrity to serve their clients and uphold the principles of justice. The origin of this concept is rooted in the need to ensure that those entrusted with representing clients and the administration of justice are trustworthy and reliable. So, in sum, this is the point of this article — it seeks to show the extent to which the systems of justice and democracy are interwoven and that they ought to work seamlessly to achieve justice for the people of this country. The players in a democracy ought to be committed to the true furtherance of justice, using constitutional law and constitutionalism to achieve that end. In a democracy, there are no venerated “holy cows”, whether they be presidents, kings, queens, bishops, politicians, legal practitioners or citizens. We ought to all be treated as equal. We hear all the rumblings from the followers of the MK party — which is hell-bent on changing the Constitution when “we come to power” — that Mpofu was unfairly treated by the Legal Practice Council. The council describes itself as “mandated to set norms and standards, to provide for the admission and enrolment of legal practitioners and to regulate the professional conduct of legal practitioners to ensure accountability”. Mpofu has been called to answer charges of alleged misconduct. Like all others in the profession, he has to avail himself to a statutory body to account for the charges against him. Legal practitioners, in order to be admitted to the profession, make a commitment, through oath, that they will become “fit and proper” for the practice. South Africa is a democracy underpinned by the Constitution and the rule of law. The MK party and its fellow travellers are seeking to subvert the cause of justice for their own political ends by suggesting that Mpofu is being persecuted. He is not. He is being asked to be accountable. Mpofu is not a loose cannon. He is accountable to the law and to the council. When the law lacks compassion, and is not in tune with prevailing societal injustices, and turns a blind to injustices perpetrated by the powerful, then it fits the description of the novelist, Dickens: it is “an ass”. Jo-Mangaliso Mdhlela is an independent journalist, a former trade unionist and an Anglican priest.