‘He lived his whole life in that fire’: the tragic story of ‘lost’ singer Jackson C Frank

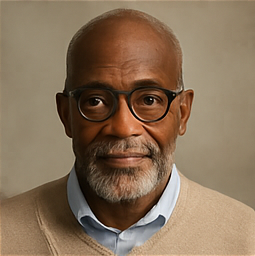

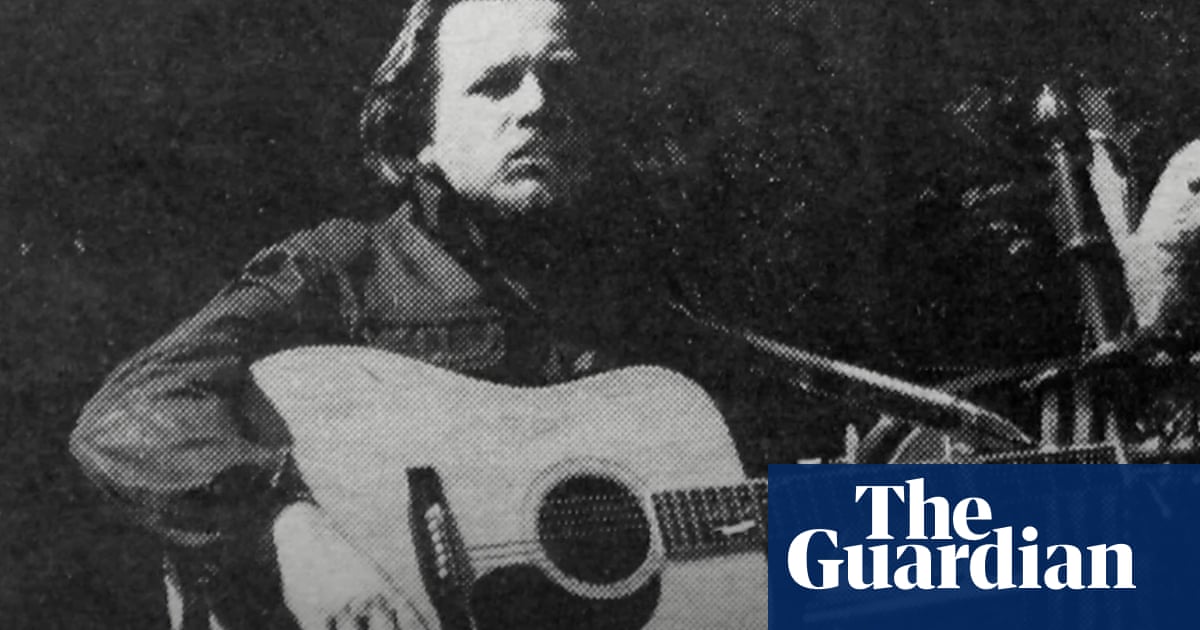

Thirty years ago, when the music writer Jim Abbott tried to track down the “lost” folk singer Jackson C Frank, he had no idea what he’d find. All he had to guide him was a tip from an old associate of Frank’s to go to a housing facility in Queens, New York, where he was told he was living. When he finally arrived there, the man he saw bore no relation to the Frank he was expecting. “All I had to go on was his album cover from 1965 when he was much younger and looked pretty dashing,” Abbott said. “This was the 90s when he was much heavier and was hobbling around looking really grouchy.” The place Frank was living in “was populated by drug addicts and hookers and, for some reason, had this gigantic sand pit in the middle of the lobby that you had to walk around. It’s very hard to weird me out,” Abbott said. “This did.” Regardless, he sought and sustained a close friendship with Frank, initially inspired by his love for the only album the artist ever released in his lifetime. A self-titled work, Frank’s album was produced in the mid-60s by a young Paul Simon, featured guitar work from Al Stewart and included haunting ballads the musician wrote that were covered at the time by folk icons such as Sandy Denny (whom he briefly dated), Nick Drake and John Renbourn. Upon its release, Frank’s album barely sold but, as happened with so many once overlooked artists, his songs were disinterred during the YouTube era leading to covers by artists such as Laura Marling, John Mayer and Counting Crows, as well as their usage in popular TV series such as This Is Us, and films as widely seen as Joker. In 2014, Abbott wrote a book about the artist’s life and music titled Jackson C Frank: The Clear Hard Light of Genius. Now, Frank’s legacy has a chance to be discovered by a whole new audience through the first documentary about his life, by the French director Damien Aimé Dupont, titled for one of his most cherished songs, Blues Run the Game. As told in the film, Frank’s story stands with the sorriest of the many doomed musician sagas, replete with tales of intense physical pain, lingering mental trauma, horrific diagnoses, an accidental shooting that left him blind in one eye, as well as periods of homelessness. Frank’s story and music were so compelling to Dupont that he pursued the film even though funds were scarce and footage of the artist, who died in 1999, was severely limited. Only an 18-second flash of silent film of Frank performing survived. More, there was a serious language issue: Dupont barely spoke English when he started the project. “I took lessons for the film,” he said with a laugh during a Zoom interview in which he was aided by a translator. As the documentary recounts, the horrors in Frank’s life began when he was just 11. In 1954, a furnace exploded at his elementary school near Buffalo, New York, causing a fire that burned to death 15 of his classmates while leaving Frank scorched more than 50% of his body. The extensive damage caused a calcium buildup in his body that deformed his joints, which the doctors tried to remedy by repeatedly breaking key bones. “You can imagine the incredible pain that caused – especially for a young boy,” Abbott said. The pain wasn’t just physical. Frank, who escaped the fire through a window after trying to help other children out, felt intense guilt for not being able to rescue more of them. That’s a surprisingly mature response to such a horrific event. “In his head, he was much older than the other children,” Dupont said. “But he had no psychological help to deal with it all. So, in his mind he lived his whole life in that fire.” View image in fullscreen Jackson C Frank. Photograph: Jim Abbott A rare bright spot during the eight and a half months he spent recuperating in the hospital arrived when a music teacher brought him an acoustic guitar, which he taught him to play. As a result of his injuries, Frank developed eccentric fingerings which gave him a uniquely textured sound. His singing also had distinction, defined by his dulcet tones as well as his ability to communicate an inner life of deep pain and empathy. Some of the songs he began to write reflected the horrors he faced as a child, including Yellow Walls, which referred to the hospital where he stayed. “No one knows me in the morning / No one sees me go walking by,” he sang. “And if I listen while no one answers / The winds can only echo a goodbye.” Frank also wrote an ode called Marlene, named for his girlfriend who died in the fire. One crushing verse expresses his guilt about surviving, interpreting the limp he developed afterwards as his punishment. “Though the fire had burned her life out / It left me little more / I am a crippled singer / And it evens up the score,” he sang. In his late teens, Frank worked as a journalist at the Buffalo News and attended Gettysburg College, but by 1962, he dropped out. A year later, he received a huge insurance payout due to his injuries. Equivalent to more than $1m today, he proceeded to fritter the money away on expensive cars and guitars, leaving him with little after just a short while. “He felt it was blood money,” Abbott said. “He didn’t want it.” Early in 1965, he went to London with his girlfriend in search of adventure. Soon he came across a booming folk scene centered at the Soho club Les Cousins, populated by key musicians such as Bert Jansch, Ralph McTell and Sandy Denny. Other artists picked up on his songs, including Paul Simon, who recorded Blues Run the Game with Art Garfunkel in an outtake, and Denny, who cut You Never Wanted Me and Milk & Honey in shattering versions. Soon after Denny met Frank, he encouraged her to quit her day job as a nurse to sing full-time. Later, she wrote a mournful song about him titled Next Time Around, which alluded to a strange and haunted man from Buffalo. Decades later, Adam Duritz of Counting Crows became obsessed by Blues Run the Game, making sure to including his version in many of the band’s live shows to this day. “It’s a perfect song,” Duritz said. “The melody is fantastic and there’s not a wasted word in the lyrics. That song has become a huge part of my life.” Duritz first heard the song through the Simon & Garfunkel version, not knowing that in the mid-60s, Simon and Frank weren’t just colleagues, they were also roommates for a while. Though the first Simon & Garfunkel album had already come out by then, it wasn’t yet successful, which inspired Simon to try to establish himself as a solo artist in London. He soon amassed enough clout there to produce Frank’s album for EMI, but the project seemed troubled from the start. Al Stewart, who played guitar on the sessions, says in the documentary that Frank was so self-conscious in the studio, he couldn’t sing or play a single note. He and Simon had to agree not to look at him before he could perform. Once the ice was broken, however, he cut the whole disc in three hours. (Simon declined to be interviewed for either the film or Abbott’s book). In London, Frank’s behavior became increasingly erratic, marked by paranoid outbursts and angry fits of jealousy. Abbott believes his mental issues stemmed directly from his childhood experience, a view shared by Frank’s mother. “She always said: ‘His problems began with that damn fire,’” he said. When he was recovering right after the event, he had spent some time in a coma. According to Dupont, “his temperature rose to above 40 degrees [celsius] which some say might have been the origin of his schizophrenia.” (In his 20s, Frank was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia). After Frank’s album bombed, he retreated back to New York, near Woodstock, where he married and had two children. His first, a son, died one day after his birth. His second, a daughter, is still alive. Over time, Frank’s behavior became so antisocial that his wife threw him out and, according to many sources, she then told their daughter her dad had died. His daughter has since refuted that story, according to Abbott. Either way, the two had no relationship after her childhood. View image in fullscreen Frank in 1998. Photograph: Linda Fine By the late 70s, Frank became a public nuisance, lumbering aimlessly around the neighborhood, sometimes stark naked. At other times he would sport a cape and sword and traipse around under the name Lochinvar. In the 80s, Frank relocated to New York City to seek Simon out, to no avail. For the next decade, he lived on the streets of the city. One day during this period, gunfire broke out between two rivals and Frank was caught in the middle, costing him an eye. Despite the risks of street life, Abbott says Frank did well by begging. “He would go out in the morning with a cup and by the end of the day it was full of money,” he said. “He could probably have talked people out of their mortgage if he wanted to.” After tracking Frank down in 1993, Abbott was able to get him back upstate where he found shelter in various boarding houses and hospitals. Despite the many issues with Frank, Abbott described him as an engaging and charismatic friend. “You could sit with him on 10 different days and talk about 10 different subjects,” he said. “He seemed to know everything.” Over time, however, Frank’s basic cognition declined. One night, Abbott took him to see a show near Woodstock by his old friend John Renbourn, and though the two talked, afterwards Frank told Abbott he didn’t know who he had been speaking to. His behavior got him thrown out of several facilities he stayed in before he finally ended up at one in Massachusetts where, at age 56, he died of a combination pneumonia and heart attack. Harrowing as much of his story may be, Dupont says: “Jackson still managed to leave his footprint in the world.” Better, it seems to be widening. “Today you can find Jackson’s songs in more and more movies and TV shows,” Abbott said. “In that sense, he’s very much here.”