Unbelievable Discovery: Toxic Lead Shaped Human Evolution for 2 Million Years!

Imagine a world where a toxic metal has been silently shaping our brains and behavior for over two million years. A groundbreaking international study is turning our understanding of lead exposure on its head, revealing that our ancestors weren't just impacted by pollution from the Industrial Revolution, but had a long, complex relationship with lead that influenced the very evolution of our species.

This eye-opening research, published in Science Advances, suggests that lead may have played a pivotal role in the development of language and cognitive abilities among hominids. Led by a team from Southern Cross University in Australia, Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and the University of California San Diego, the study combines innovative fossil geochemistry with cutting-edge brain organoid experiments to reveal startling insights about our ancestors.

For decades, scientists believed that exposure to lead was primarily a modern phenomenon, driven by industrial activities like mining and the use of leaded products. However, by analyzing fossil teeth from various hominid and great ape species, including Australopithecus africanus and Homo sapiens, researchers discovered traces of lead that date back nearly two million years. These findings highlight that lead exposure was a consistent part of our evolutionary history, with chemical signatures indicating intermittent lead contact from environmental sources and even from the body’s own reserves.

Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau, the study’s lead researcher, stated, “Our data show that lead exposure wasn't just a product of the Industrial Revolution – it was part of our evolutionary landscape.” This suggests that our ancestors’ brains developed in a toxic environment, potentially shaping their social behaviors and cognitive abilities over millennia.

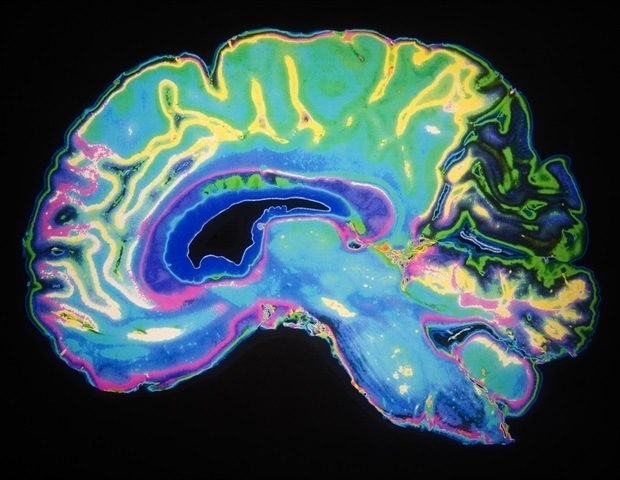

To dive deeper, the research team explored how lead exposure affected brain development by using brain organoids—miniature lab-grown brains. They compared the effects of lead on different versions of a key developmental gene, NOVA1, crucial for speech and language development. It turned out that the archaic NOVA1 variant found in Neanderthals and other extinct hominids was more susceptible to lead’s toxic effects than the modern human version, which may have evolved as a protective mechanism.

Professor Alysson Muotri from UC San Diego highlighted how this adaptation could explain why modern humans have better resilience against lead's neurological impacts. “This study suggests that our NOVA1 variant may have offered protection against the harmful neurological effects of lead,” he explained. This insight presents an extraordinary link between environmental pressure and genetic adaptation.

The study also revealed that lead exposure disrupted important neurodevelopmental pathways linked to social behavior and communication. Essentially, this means that lead might have had a role not only in our survival but in refining our language abilities, as pointed out by Professor Manish Arora of Mount Sinai Hospital. “This study shows how our environmental exposures shaped our evolution,” he noted.

As we look at the world today, where lead exposure still poses serious health risks, especially for children, this research serves as a stark reminder of the long-term consequences of environmental toxins on human biology. It reinforces the idea that our struggles with lead are not just modern-day issues but inherited challenges that are deeply rooted in our evolutionary past.

In essence, this study not only rewrites the history of lead exposure but also underscores the intricate dance between our genes and the environment—a relationship that has shaped humanity for millennia and will continue to do so.