Revisiting Aldo Leopolds Call to 'Think Like a Mountain' Through Literature

If one were to encapsulate the essence of the contemporary environmental movement into a single guiding principle, one might gravitate towards the phrase Think like a mountain. This evocative phrase has become a staple in the promotional literature of various conservation organizations and originates from Aldo Leopolds seminal work, A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949. In this influential text, Leopold dedicates a chapter to the perils of wolf hunting, highlighting the consequences of shortsightedness in how we interact with nature.

Aldo Leopold, early in his career as a young officer in the Forest Service, was a proponent of a campaign by sportsmen to eradicate large predators from the Southwest, believing that this would boost the deer population. However, as he began drafting the very book that would significantly shape the environmental ethics of the twentieth centuryinitially entitled Thinking Like a MountainLeopold underwent a profound transformation in his understanding of ecological balance.

In one poignant passage, Leopold reflects on the consequences of his earlier actions: "I have lived to see state after state extirpate its wolves. I have watched the face of many a newly wolfless mountain, and seen the south-facing slopes wrinkle with a maze of new deer trails. I have seen every edible bush and seedling browsed, first to anaemic desuetude, and then to death." His observations highlight a dramatic shift in perspective as he realizes that the overpopulation of deer leads to starvation and ecological decaya stark reminder that misguided interventions can yield disastrous unintended consequences.

Leopolds criticism extends to hunters, ranchers, and game managers who, he argues, lack the foresight to understand the repercussions of their actions. He notes, They have not learned to think like a mountain. Hence we have dustbowls, and rivers washing the future into the sea. This insight about humanity's relationship with the natural worldone where the role of conqueror often leads to self-destructionwas not solely Leopold's innovation but has roots in earlier ecological thinkers like Alexander von Humboldt, who famously stated, In this great chain of causes and effects, no single fact can be considered in isolation.

Leopold's contribution was to weave this understanding into a moral framework that governs our interactions with nature. To think like a mountain entails embracing the idea that excessive caution often leads to greater risks, and it echoes the sentiment that in wildness is the salvation of the world, as expressed by Henry David Thoreau. It is an implicit acknowledgment of the mountains indifference to human existence, where respect for nature is paramount because nature does not inherently respect humanity.

In recent years, novelists with ecological sensibilities have increasingly posed a question inspired by Leopolds philosophy: How can writers think like a mountain? Amitav Ghosh, in the conclusion of his work The Nutmegs Curse (2021), insists that nonhumans can, do, and must speak, emphasizing the urgent necessity of reintroducing nonhuman perspectives into our narrativesespecially as humanity faces impending environmental crises.

However, achieving this restoration in literature raises complex issues. How can narratives, typically focused on individual human experiences, reflect a worldview where such experiences are not central? How do authors navigate the thin line between engaging with ecological themes and avoiding clichs, simplistic advocacy, or outright inauthenticity?

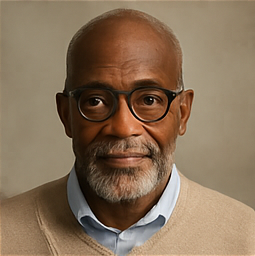

These contemplations are becoming increasingly pressing as we confront an era defined by environmental anxiety. Yet, they are not novel; writers have grappled with these themes over the decades. One of the notable figures who adeptly explored the relationship between humanity and nature is Charles Ferdinand Ramuz, whom many regard as the preeminent Swiss novelist of the twentieth century. His life and work were deeply intertwined with the powerful mountains that surrounded his home in the Swiss canton of Vaud, where he published over twenty novels throughout his life.

Ramuz had an acute awareness of the mountains that loomed over him, often portraying them as both majestic and menacing in his narratives. His novel Derborence (1934), first translated into English as When the Mountain Fell (1947), recounts a real historical event from 1714, where a mountain landslide obliterated a village. The first half of the novel vividly depicts the catastrophic landslide that took lives and reshaped the land, while the latter half reveals a survivor emerging from the rubblea chilling testament to the mountains overwhelming power.

In another of his works, Si le soleil ne revenait pas (What If the Sun..., 1937), the story unfolds under a steep mountain that casts an ominous shadow, blocking sunlight for half the year. When a local oracle predicts a year when the sun might not return, despair grips the village, unraveling their sanity.

In Great Fear on the Mountain, published in 1926, Ramuz illustrates the tension between human ambition and natures formidable reality. The narrative centers on an impoverished Alpine village that debates the risks of sending a second expedition into a high mountain valley to access a pasture beneath a massive glacier. With their cattle starving, the villagers weigh the desperate need for sustenance against the haunting memories of a previous expedition that ended in tragedy. The older generation expresses caution about exhausting natural resources, while the younger villagers, desperate for survival, push for action, culminating in a vote that favors exploitation over restraint.

Despite the Transylvanian backdrop, Ramuzs work isnt confined to Gothic tropes; he finds horror in the sublime beauty of nature. His characters confront the ominous aspects of their environment, as when they navigate a gorge filled with unsettling noise, raising the question of what might compel them to shout. The mountain, while picturesque, harbors a darkness that drives the expedition to madness.

As the men climb higher, they encounter a pastoral scene that is idyllic yet eerie, with grass soft underfoot and an old chalet nestled in the rocks. However, Ramuzs portrayal of nature leads to catastrophic results. The expedition devolves into chaos as livestock succumb to madness, accidents unfold, and the glacier ultimately descends upon the village, a harrowing metaphor for natures indifference to human suffering.

In Ramuzs fiction, the mountain often emerges as a powerful antagonist, highlighting the futility of human endeavors against nature's vastness. The narrative structure of Great Fear on the Mountain is notably unconventional, eschewing traditional protagonist-focused storytelling in favor of a collective experience among characters. This fluidity in perspective and the shifting narrative voice serve to underscore the inherent equality of human and nonhuman experiences, leveling the hierarchical distinctions often found in literature.

The challenge of writing ecological narratives lies in acknowledging our interconnectedness with nature while grappling with humanity's self-destructive tendencies. Ramuzs work presents a stark reminder of our cosmic insignificance, as he questions whether individual human lives matter in the grand scheme of existence. The sky was arranging itself, without paying any attention to us, he writes, prompting readers to contemplate their place within the larger tapestry of life.

Ultimately, the task of ecological literature is to navigate these complex dynamics, eliciting introspection regarding our relationships with the natural world. As we confront the pressing environmental issues of our time, the question remains: Can humanity coexist sustainably without bringing calamity upon itself? As it was in Leopolds era, this remains an open and critical question for our age.