Exploring the Unique World of Sourdough: A Personal Journey with the Citizen Science Sourdough Project

A couple of years ago, I found myself captivated by an intriguing research initiative undertaken by the HealthFerm Citizen Science group, in collaboration with two prestigious institutions: VUB Brussels and ETH Zurich. This innovative study, known as the Citizen Science Sourdough Project, aimed to gather and map a diverse range of micro-organism samples from sourdough starters, with the enthusiastic participation of everyday citizens like myself. As a passionate sourdough aficionado, I eagerly submitted a sample, fully immersed in the excitement of contributing to scientific research. However, as the months turned into years, I gradually forgot about the project and the sample I had sent.

That was until yesterday, when I received an email notifying me that the results of my sourdough starter sample had finally arrived! My sample was identified by the ID 4f6d6, and I couldnt wait to dive into the findings.

The report consists of two parts, and the first section compares my sourdough starter to the other submissions collected during the study. The researchers analyzed various factors: (A) the presence of possible twins found across Europe, (B) fermentation preferences such as temperature and time, (C) acidity and age of the starters, and (D) the concentration of yeast and bacteria cells.

Starting with the personalized result report, my sourdough starter is affectionately named Stinkiea name that perfectly encapsulates its character! I typically store Stinkie in the refrigerator during the weekdays and feed it rye flour at a 100% hydration level, meaning I use equal parts flour and water. This feeding method can produce a tangy flavor, and if not properly cared for, it can take on a rather pungent aroma!

In the report, I discovered that there are three starter samples in Switzerland that are exact matches to Stinkie! Additionally, there are two other twins found in Greece and Finland. This discovery is particularly significant to me, as the distinctiveness of each sourdough starter is influenced heavily by its local environment, including climate, type of flour used, and feeding techniques. The warm weather in Greece and the nutty, wheaty flour available there contrasts sharply with what Im accustomed to in Belgium. Likewise, the Finnish climate is characterized by its rye-dominant grain landscape, making for a very different baking experience. One can only speculate whether these other starter caretakers also utilize the refrigeration method I do. Perhaps the Finn, for example, prefers imported flour instead?

Moving on to fermentation preferences, my starter, when compared to others using rye meal, is found to be more acidic and fluffier, likely because I occasionally incorporate wheat flour into my feedings. Interestingly, while my starter is maintained at cooler temperatures, the bread I produce with it tends to be much tarter, particularly when I proof the dough in the fridge. As for acidity and age, Stinkie has a pH level of 3.7, which aligns closely with the average of all submitted samples. However, it's worth noting that while the average age of the starters submitted was less than five years, Stinkie boasts a remarkable age of 11 years! This longevity is astonishing, considering the countless refreshes it has undergone over the years.

In terms of the yeast and bacteria present in Stinkie, I discovered that it contains approximately 41.69 million yeast cells per gram, slightly exceeding the typical starter. Additionally, it has a higher bacterial count of 2.82 billion cells per gram, which could be attributed to its advanced age. It raises an intriguing question: is there a discernible connection between the starter's age and its microbial population? I suspect that researchers will explore these potential correlations in greater depth in forthcoming publications.

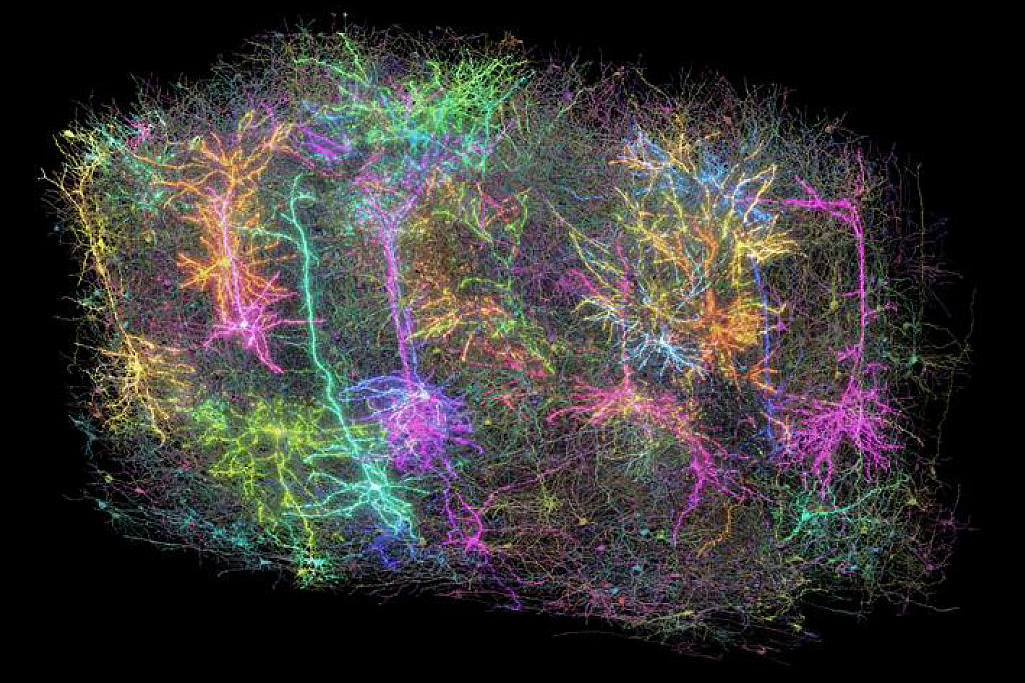

The second part of the report provides a closer examination of the yeast and bacterial fingerprints associated with Stinkie. It features a graph displaying five different vertical bars that delineate the unique combinations of typical sourdough classes, with a sixth bar representing my starters specific profile. Notably, for the bacterial fingerprint, Stinkie most closely resembles class 3, albeit with one species dominating: Lactobacillus brevis, constituting a staggering 89.5% of the sample. This dominance likely stems from my storage method and the specific flour and humidity conditions I employ. Interestingly, I would have preferred a bit more diversity within the bacterial communityno San Francisco sourdough flora here!

The scenario is similar for the yeast fingerprint; Stinkie aligns with sourdough profile 3, where multiple yeast species are typically present. However, in my case, Stinkie exhibits a monoculture, with Saccharomyces Cerevisiae being the sole yeast type present at 100%. While this consistency yields reliable results and enhances my familiarity with Stinkies behavior, I cant help but wonder what flavor variations might emerge if I were to change my feeding regimen to twice daily at room temperature for an extended period.

For those who find the results challenging to interpret, the research team has created a multilingual AI assistant named Dough-Pro to facilitate exploration of the data. While the name is amusing, I found the AI to be less sophisticated than expected, as the provided link redirected to a familiar site. I would prefer to consult the comprehensive report explanation guide and FAQ, which I hope was crafted with input from the researchers themselves.

Overall, I have a profound appreciation for this kind of citizen-driven research. Although it did take some time for the results to be processed, the wait was undeniably worthwhileeven if I had completely forgotten about it. It is incredibly rewarding to witness how Citizen Science actively engages individuals in providing samples, and I am excited about the prospect of receiving similar insights from other studies I have participated in, such as one focusing on gut microbiota.