A Night of Injustice: One Woman's Ordeal in the California Criminal Justice System

On February 16th, after an exhausting day at work, I returned home, utterly drained and ready to collapse into bed. However, my plans for a peaceful evening were quickly shattered when my ex-boyfriend attacked me. Feeling frightened and desperate, I called the police around midnight, dreading the thought of being seen as a victim, a label I had never wanted to embrace.

To my shock, when the police arrived, they did not view me as the victim in this situation. According to California Penal Code 13701, officers are mandated to make an arrest in domestic violence incidents, regardless of the circumstancesit could be me or my ex. In a twist of fate, they chose to arrest me.

One of the arresting officers explained with an air of resignation, Its the law. I could lose my job if I dont arrest someone. I wanted to scream in frustration. I had called for help, only to find myself being taken away in handcuffs, while my ex, who had threatened to kill me, received resources and support. How was this even remotely fair?

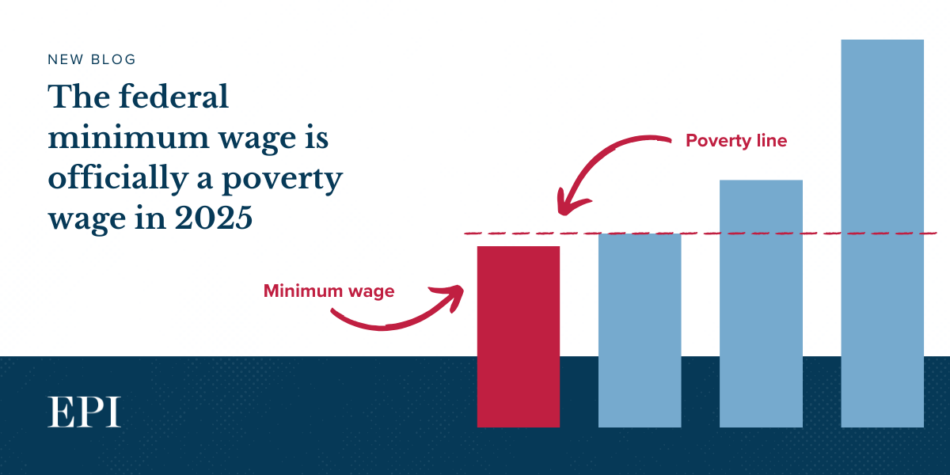

Later, when the district attorney dropped my charges due to a lack of evidence, I learned that the very law that was designed to protect victims had become a double-edged sword. The intent behind the statute, which was established following the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, was noble, aiming to provide greater safety for survivors. However, almost three decades later, it has remained untouched and is now enabling undertrained officers to make hasty and flawed arrestssuch as mine. This not only wastes valuable resources but also contributes to the perpetuation of the prison industrial complex.

At the local jail, I was bruised and smelling of beer, having been struck by an open can that my ex hurled at my head. I managed to contact a friend on the East Coast, desperately asking her to find me in the county jail and post my bail. Three long hours later, after the processing was completed, I was exhausted and assumed I wouldnt make any new friends before my release. But to my surprise, as I entered a cell full of women, I quickly felt a sense of camaraderie.

What are you in for? asked Simone, a bright-eyed Indian girl who sat up as soon as the metal door slammed shut behind me. She was a traveling nurse from Georgia, and her arrest stemmed from a DUI after a bad date. You dont seem like you belong here, said Veronica, a Latina girl with oversized glasses, who later revealed she had shoplifted a birthday gift for her mother. When I recounted my experience, the other girls leaned in, captivated by my story.

Fuck the police! exclaimed Amber, her wide eyes flashing with anger. She was in for possession of drugs, and if convicted, this would be her third strike. In that moment, I felt relieved that they believed me instantlythere was no skepticism or doubt, only acceptance. This was in stark contrast to the sheriff who had frisked me upon entry and bemusedly asked, So, you beat him up?

Many of the women in the cell had previous experiences with the justice system. They exchanged gossip about what had changed since their last stints in jail. Yet beneath the surface chatter, I could sense a profound grief. More than one girl broke down in tears, grappling with their circumstances and questioning how they had ended up back in this place.

It dawned on me: for these women, most of whom were younger than I was, the system was not something to challengeit was an unyielding tide that dragged them under. I realized that I could potentially provide them with something to fight back with: knowledge and empowerment. I could share what I had learned over my two decades in government and activism.

The hours dragged on as we were escorted for body scans, photographs, and x-rays. I wondered how my friend was faring with the bail arrangements. The bail was set at $50,000, a standard amount in California for charges like mine. It felt humiliating to ask my frienda former journalist and civil attorney, elegant and resourcefulto navigate the complexities of bail on my behalf. But I couldnt afford to wait in jail until court three days later. Who would take care of my cats? What would happen to my job?

The justice system doesnt operate solely on facts; it also relies heavily on instinct, which is often biased and not neutral. Spotting a decal on the cell window that listed bail bondsmen, I began making calls. However, without my phone, I could only recall useless numberslike my dads old cellphone from high school. The first three bondsmen laughed at my requests for help, and I felt a sense of defeat wash over me. Finally, I called a fourth number.

Hello? came a gruff voice. I explained my situation, lowering my tone as I mentioned I worked for a D.C. think tank and authored bookswas I trying to sound more credible? Or was I worried about how the other women would perceive me?

As I spoke, I could hear keys tapping on the other end. He was checking my story. So, who can co-sign your bond? he eventually asked. I gave him my friends name but had to admit that I didnt know her number by heart. No problem. I found her online, he replied quickly.

Within five minutes, my friend was on the line. The moment I heard her voice, I broke down in tears. Are you safe? she asked, her concern palpable. I sobbed that I was fine, and she quickly moved on to the necessary arrangements: What do we need to do to get you out?

Heather, Jons coworker, explained that my bail was set at $50,000, but my friend hesitated until Heather clarified that she would only need to pay ten percent. My friend rapidly agreed, and as they organized the payment via Venmo and the requisite paperwork, I couldnt help but reflect on how rare this situation was. Most individuals do not have a friend with $5,000, time, and resources to pull together on a moments notice. I witnessed other girls, desperate, struggling to gather their ten percent.

When I called back, Jon surprised me by saying that Heather was already at the jail, even before all the paperwork was completed. I had a gut feeling, he explained. I thanked him, but his words lingered in my mind. How much of his gut reaction was influenced by perception and privilege? The justice system doesnt rely solely on facts; it thrives on instinct, which is shaped by race, class, and voice. It determines who receives help and who remains unheard. I pondered this as I listened to Jon turn down other women, and I began answering questions from the girls in the cell.

Initially, the conversations were lighthearted, with the girls curious about my job. I spoke about government, Trump, and democracy. But as the hours passed, I transitioned into teaching them about civics. They asked about policies, who to contact for help, and I provided them with names and resources, reminding them that its not hopeless.

A few hours later, two new girls were brought into our cell: Nadia, an Indian girl who looked only sixteen, and Zoe, an Asian fourth-year student at the local university. We exchanged details about our arrests, and something felt amiss. Both Nadia and Zoe had called for help, and both had faced the same outcome: their partners walked free while we found ourselves behind bars. The arresting officers words about the penal code echoed in my mind as I pressed them for more details. Nadia repeated my questions, clearly trying to comprehend how she had ended up incarcerated. I tried to comfort her because I didnt blame her for being confused.

Just then, a new sheriff with curly hair opened our cell door. She called out my last name and gestured for me to follow her. I was escorted into a new cell, which served as the final stop for everyone on their way out. A red line painted on the walls guided us toward freedom. Soon, Zoe and Nadia joined me; Zoes bail had come through. Nadia was being released as well. We watched as the other girls from our cell were taken upstairs, and while it may have been irrational, I felt a wave of relief wash over me that I wasnt going with them. It would have felt like another step deeper into a system that was already swallowing us whole.

Zoe and Nadia opened up more about their arrests as they sought to understand what to expect in court. Should I hire a lawyer? Zoe asked, hesitantly adding, Should they be Asian?

Why? I inquired, curious about her reasoning.

She shrugged, I dont know. Maybe theyd understand better? I urged her to find a lawyer, regardless of their ethnicity, and she assured me that her parents would be able to find the money.

The curly-haired sheriff returned, barking at Zoe and Nadia to get up. Zoe glanced back at me with wide eyes as they followed the red line out. I was puzzled by their sudden release but felt glad they were getting out.

Another half hour crawled by before the curly-haired sheriff came back for me. She gestured for me to stand up, and I pointed at myself, eyebrows raised in confusion.

Yes, you! she hollered. She opened the door and directed me to stand on the now-familiar red line, facing the wall.

You need to do a mental health check before youre released, she informed me. Follow me.

At this point, I couldnt hide my sigh. Of course, I would need a mental health check. The consequences of my arrest were not over yet. The sheriff asked me why I was there, and I explained the situation with my ex. She shook her head in disbelief. Damn, girl, she said. Fight those charges, okay? But first, think carefully about what you need to say to get out. You dont want to go back in, right?

I thanked her with a small smile, but after spending sixteen hours in jail, the requirement for a mental health check felt like yet another humiliation courtesy of one officers misguided judgment.

Still, I complied. I was led into a wooden booth, where an Asian staff therapist awaited my arrival. The questions she asked were straightforward. Yes, I had a place to go after my release. No, I didnt want to harm myself. Yes, I was working with a therapist. I should have felt relieved that the questions were uncomplicated, but I was just exhausted. The screening felt like a setup, a subtle attempt to validate the arresting officers narrative that he had concocted.

After ten confusing minutes, I caught the curly-haired sheriffs gaze through the booths glass door. She rolled her eyes and went to inquire whether I was cleared for release. Suddenly, I found myself being walked down the red linetoward freedom. Fight, okay? the sheriff said, handing me off to another officer.

The next sheriff handed me a slip for my belongings. Its your ticket to freedom, she smiled, her warmth feeling almost foreign after my recent experiences. I received my clothes back, the scent of stale beer having long faded. I couldnt even muster a snarky thought about the length of my stay; all I wanted was to go home.

I signed a form regarding my bond, took a slip with my court date, and found myself in a sitting area alongside Zoe and Nadia, now dressed in their street clothes. We exchanged smiles but remained silent. After hours of bonding through forced proximity, the gift of freedom meant the choice to be silent.

As I powered up my phone, I noticed a slew of texts from my East Coast friend, who had been waiting up to confirm my release. She had spent nearly nineteen hours working on my behalf. I felt fortunate. Not everyone has a friend with the time, money, and resources to assist in such a crisis. I called her back.

This isnt over, she gently reminded me. The next step would involve securing a criminal defense attorney for my upcoming court date. She had already begun reaching out to her network. I sighed heavilynone of this should have been necessary.

A broken system does more than just punish; it drains our time, resources, and trust in justice. How many hours and how much energy have been wasted trying to rectify one officers poor decision? How many women endure this nightmare alone? When I shared stories of Zoe and Nadia, my friend didnt hesitate to support my desire to fight for change: Its the right thing to do. The system expects women like us to remain silent due to the stigma or trauma surrounding our experiences. But I refuse to be silent. Silence protects no one, and this is no longer just my story.

As the doors swung shut behind me, I found myself already piecing together my to-do list: policy, legislation, change. Yet I knew that change isnt merely about rewriting laws. The statute that placed me in this situation was intended to be a shield for survivorsand it failed. Sometimes, the chasm between what the law promises and the realities faced by survivors is vast. At times, that gap transforms into harm.